2008 quelônios delta_jacui_port

-

Upload

projeto-chelonia -

Category

Education

-

view

181 -

download

0

Transcript of 2008 quelônios delta_jacui_port

47Artigos Técnico-Científicos Natureza & Conservação - vol. 6 - nº2 - Outubro 2008 - pp. 47-60

Quelônios do delta do Rio Jacuí, RS, Brasil: uso de hábitats e conservação

INTRODUÇÃO

As unidades de conservação asseguram, numprimeiro momento, a preservação das espé-cies de seu interior, porém, estão sujeitas a in-cêndios e outras ameaças difíceis de observar.Assim, dependendo de seu tamanho e locali-zação, a extinção de pelo menos uma peque-na parte de suas espécies é inevitável(Rodrigues, 2005). No Brasil as unidades deconservação estaduais, federais e terras indí-genas cobrem, aproximadamente 23% da su-perfície terrestre do país (Rylands & Brandon,2005) e são áreas de suma importância à con-servação de espécies da fauna e flora. A legis-lação brasileira prevê um Sistema Nacionalde Unidades de Conservação da Naturezaque, entre outras atribuições, institui a criação

de Parques e Áreas de Preservação Ambiental(APA). Os Parques têm como objetivo básicopreservar ecossistemas naturais de grande re-levância ecológica e beleza cênica, possibili-tando a realização de pesquisas científicas e odesenvolvimento de atividades de educação einterpretação ambiental, de recreação em con-tato com a natureza e de turismo ecológico.As APAs são áreas geralmente extensas, comum certo grau de ocupação humana, dotadasde atributos estéticos ou culturais especial-mente importantes para a qualidade de vidae o bem-estar das populações humanas.Conforme preceitua a Lei n° 9.985, de 18 de ja-neiro de 2000, tem como objetivos básicosproteger a diversidade biológica, disciplinaro processo de ocupação e assegurar a susten-tabilidade do uso dos recursos naturais.

Incluído na categoria parque desde 1976, oParque Estadual Delta do Jacuí historicamen-

Quelônios do delta do Rio Jacuí, RS, Brasil: uso de hábitats e conservação

Clóvis Souza Bujes, Dr1

• Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biologia Animal, Departamento de Zoologia - Universidade Federal do RioGrande do SulLaura Verrastro, Drª• Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biologia Animal, Departamento de Zoologia - Universidade Federal do RioGrande do Sul

RESUMO. O inventário realizado no Parque Estadual Delta do Jacuí, visando conhecer a fauna dequelônios, seus hábitats e as principais ameaças às espécies, mostrou a ocorrência de uma espéciepertencente à família Emydidae, a tartaruga-tigre-d’água Trachemys dorbigni (Duméril & Bibron,1835), e três espécies pertencentes à família Chelidae, o cágado-preto Acanthochelys spixii (Duméril &Bibron, 1835), o cágado-de-pescoço-de-cobra Hydromedusa tectifera Cope, 1870 e o cágado-cinzaPhrynops hilarii (Durémil & Bibron, 1835). A tartaruga-tigre-d’água foi a mais abundante, represen-tando mais de 66% das capturas. O cágado-cinza contribuiu com 21% das capturas, o cágado-preto,com 8% e o cágado-de-pescoço-de-cobra com 5%. As espécies ocuparam diferentes tipos de hábitats,aqui categorizados como banhados, canais, sacos, rios, canais de irrigação, quadras de arroz, poçase cavas. A destruição e a fragmentação do hábitat, a poluição e a desinformação humana foram asprincipais ameaças aos quelônios no Parque.

Palavras-chave: Testudines, ocupação humana, alteração antrópica, educação conservacionista

48Artigos Técnico-Científicos Natureza & Conservação - vol. 6 - nº2 - Outubro 2008 - pp. 47-60

Clóvis Souza Bujes - Laura Verrastro

te vem sofrendo com a ocupação irregular e adegradação ambiental. A região do Delta dorio Jacuí passou por alterações profundas nosúltimos 50 anos decorrentes do declínio eco-nômico da pesca, da navegação e da pequenaprodução agrícola e leiteira. Além disso, o de-pósito de resíduos e efluentes provenientesdas indústrias de curtume do Vale do rio dosSinos contribuem para a poluição de grandeparte das águas que circundam as ilhas(Branco-Filho & Basso, 2005).

Situado na Região Metropolitana de PortoAlegre, no encontro dos rios Jacuí, Gravataí,Caí e Sinos, o parque é formado por 30 ilhas eporções continentais com matas, banhados ecampos inundados. É uma das áreas úmidasmais importantes do Estado do Rio Grandedo Sul integrando um mosaico de ecossiste-mas que representam um ecótono ou transi-ção entre as áreas mais altas da DepressãoCentral e o Sistema Lagunar Costeiro(Oliveira, 2002). A ocupação humana, inicia-da a partir do século XVIII, gerou uma popu-lação que convive com a rica diversidade bio-lógica da área: aproximadamente 78 espéciesde peixes (Koch at al. 2002), 24 espécies deanuros (Melo, 2002), 210 espécies de aves(Accordi, 2002), além de espécies ameaçadas,como o jacaré-de-papo-amarelo (Caimanlatirostris) e o gato-do-mato (Oncifelis geoffroyi).

As populações de tartarugas em muitas partesdo mundo são fortemente impactadas pelasatividades humanas, desenvolvimento e urba-nização. Aproximadamente dois terços das es-pécies de tartarugas terrestres e de água docedo mundo estão listadas como ameaçadas pe-la IUCN e mais de um terço ainda não foi ava-liada (Turtle Conservation Fund, 2002). A ex-ploração humana das espécies de quelôniostem por conseqüência o declínio de muitaspopulações, o extermínio local e mesmo a ex-tinção de espécies (Thorbjarnarson et al.,2000). Inúmeros trabalhos citam a ação do ho-mem como principal fator na destruição efragmentação de hábitats (e.g., Gibbons et al.,2000). Como efeitos negativos estão incluídasfragmentação da estrutura genética (Rubin etal., 2001), conseqüências demográficas

(Garber & Burger, 1995; Lindsay & Dorcas,2001) e mortalidade (e.g., através de atropela-mento por automóveis, Gibbs & Shriver,2002). Contudo, algumas espécies de quelô-nios podem ser muito resilientes às atividadeshumanas e continuar a existir em ambientesaltamente modificados, enquanto outros ani-mais silvestres desaparecem (Mitchell, 1988).

Dados descritivos sobre o status de popula-ções e de comunidades podem servir comouma linha de partida para futuras investiga-ções dos efeitos da urbanização sobre os or-ganismos, podendo-se, assim, direcionar es-forços de conservação das espécies e dos am-bientes que elas ocupam (Conner et al., 2005).Diante disso, as propostas do presente estudoforam: (1) conhecer as espécies de tartarugasque ocorrem no Parque Estadual Delta doJacuí; (2) descrever os hábitats ocupados e (3)identificar as potenciais ameaças em um am-biente fortemente alterado pelo homem.

MATERIAL E MÉTODOS

O Parque Estadual Delta do Jacuí (PEDJ) éuma unidade de conservação localizada naporção centro-oriental no estado do RioGrande do Sul, Brasil (29º53’ e 30º03’ S e51º28’ e 51º13’ W). O PEDJ conta com uma su-perfície superior a 21 mil hectares, compreen-dendo terras emersas continentais e 30 ilhas(Oliveira, 2002). Conforme Maluf (2000), o es-tado do Rio Grande do Sul localiza-se emuma região climaticamente intermediária en-tre a região Temperada (com temperatura mé-dia de 13°C no mês mais frio) e a Subtropical(com temperatura média entre 15 e 20°C nomês mais frio). Segundo o autor, a região deestudo apresenta um tipo climático ST UMv(Subtropical com verões úmidos), cuja tempe-ratura média anual é de 19°C, temperaturamédia de 14°C no mês mais frio, precipitaçãopluvial anual de 1309 mm, deficiência hídricaanual de 50 mm e excesso hídrico anual 210mm. O regime hídrico alterna períodos de es-tiagem e de cheia, obrigando a vegetação a seadaptar a essa condição. Daí a presença mar-cante dos banhados, aqui conceituados comocorpos d’água permanentes ou temporários,

49Artigos Técnico-Científicos Natureza & Conservação - vol. 6 - nº2 - Outubro 2008 - pp. 47-60

Quelônios do delta do Rio Jacuí, RS, Brasil: uso de hábitats e conservação

sem uma bacia bem determinada, de contor-no e perímetro indefinido e sem sedimentospróprios, apresentando vegetação emergenteabundante e poucos espaços livres(Ringuelet, 1962 apud Oliveira, 1998). Osbanhados apresentam formações vegetaisdominadas pelas espécies sarandi-brancoCephalanthus glabratus (Rubiaceae), aguapé-gigante Thalia geniculata (Marantaceae), carne-de-vaca Psychotria carthagenensis (Rubiaceae),espadana Zizaniopsis bonariensis (Poaceae), erva-de-bicho Polygonum stelligerum (Polygonaceae),além da abundância de macrófitas como agua-pé Eichornia azurea (Pontederiaceae) e o capim-camalote Panicum elephantipes (Poaceae) quese desenvolvem nas margens dos sacos, doscanais entre as ilhas e às margens destas, ondea correnteza não é muito pronunciada (Olivei-ra, 1998).

Neste estudo, com relação aos cursos d’água,foram considerados dois tipos de ambientes:(1) permanentes e (2) temporários. Os per-manentes referem-se a todos os ambientes

que se mantêm alagados, mesmo durante osperíodos de seca, tais como: banhados inter-nos densamente vegetados, canais (curso deágua natural ou artificial, com água em mo-vimento, que forma uma ligação entre duaslinhas de água), sacos (um ambiente semife-chado ligado ao rio através de uma estreitacomunicação) e rios. Como temporários fo-ram considerados todos os corpos d’águaque sofrem grandes oscilações de volume, eque na maioria das vezes secam totalmente,em curtos período de tempo: canais de irri-gação (utilizados para transporte de águados canais principais para as quadras de ar-roz), quadras de arroz (ambientes similaresaos canais secundários em termos de fluxo deágua, porém em geral mais rasos), poças(áreas de campo de pequena extensão que sealagavam em períodos de chuva) e cavas(áreas de extração de areia próximas aos ba-nhados e rios).

Os quelônios foram coletados em três locaisno interior do PEDJ (FIGURA 1). O primeiro,

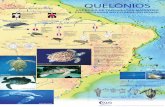

Figura 1: Localização do Parque Estadual Delta do Jacuí, RS – Brasil e os locais de coleta na Fazenda Kramm (FK), Ilha dasFlores (IF) e Ilha da Pintada (IP).

Rio Jacui

Rio Cai

Rio Sinos

RioGravatai

PORTO ALEGRE

Américado Sul

Argentina

Uruguai

Rio Grande do Sul

BRASIL

50Artigos Técnico-Científicos Natureza & Conservação - vol. 6 - nº2 - Outubro 2008 - pp. 47-60

Clóvis Souza Bujes - Laura Verrastro

a base do projeto, se localiza na Ilha daPintada (IP). A área para estudo dos quelô-nios tinha aproximadamente três hectares,uma área urbanizada que incluía, no centro, ocanal Mauá; ao norte do canal, um estaleirode grande porte e em pleno funcionamento;ao sul, o pátio da sede administrativa doPEDJ (local utilizado pelas tartarugas para ni-dificação); a oeste, construções humanas (re-sidências, comércio, escolas) às margens e so-bre as áreas de banhado; e, a leste, o rio Jacuí(30°01’52”S, 51°15’07”W). O segundo local, aFazenda Kramm (FK), é uma propriedadeagropecuária situada nos limites do PEDJ, aosul do rio Jacuí, em frente às ilhas do Cravo eCabeçudas. A área utilizada para coleta dedados foi de, aproximadamente, nove hecta-res, incluindo banhados, quadras de planta-ção de arroz e as cavas (crateras originadas daextração irregular de areia) numa área de ma-ta de restinga, vizinha à fazenda (29°58’59”S,51°18’58”W). O terceiro local situa-se na Ilhadas Flores (IF), numa área de aproximada-mente seis ha, incluindo os banhados e a es-trada (cujas margens os quelônios utilizamcomo sítio de nidificação) a duzentos metrosda margem leste do rio Jacuí (29°58’48”S,51°16’22”W). A área da IP está distante 8,5Km da FK, e esta a 5,3 Km da IF, que fica a 5,2Km da IP.

As expedições ocorreram de setembro de2003 a agosto de 2004 na IP, de setembro de2004 a agosto de 2005 na FK, e de setembro de2005 a agosto de 2006 na IF. O esforço amos-tral foi de dois a três dias consecutivos por se-mana, entre setembro e janeiro, e de um diapor semana, nos demais meses. Em todas asáreas as capturas foram realizadas manual-mente e com utilização de seis armadilhas dotipo “box-trap” (dimensões 600Lx360Ax800Pmm), iscadas com carcaça de frango. As ar-madilhas foram colocadas semi-submersas,dispostas a cerca de 40 metros de distânciaumas das outras, ao longo das margens e per-maneciam no local por um período mínimode 24 horas. As armadilhas eram revisadas acada três horas e, a cada expedição, se alter-nava sua localização, visando maximizar acobertura de cada área.

Após identificação, pesagem e coleta de da-dos biométricos, cada tartaruga capturada foimarcada individualmente com um entalheem seu escudo marginal (Cagle, 1939) e pos-teriormente solta no mesmo local da captura.O sexo dos adultos foi determinado a partirdas características sexuais secundárias, quaissejam, posição da cloaca em relação à mar-gem posterior do plastrão, existência de con-cavidade no plastrão e ocorrência do proces-so de melanização.

As considerações acerca das ameaças às espé-cies e aos seus hábitats no PEDJ, discutidasnesse trabalho foram realizadas a partir deobservações diretas no ambiente e através deentrevistas informais com a população huma-na local.

RESULTADOS

Foram capturados 208 exemplares de quatroespécies de quelônios de água doce: uma es-pécie pertencente à família Emydidae, a tar-taruga-tigre-d’água Trachemys dorbigni(Duméril & Bibron, 1835) (N = 137), e trêsespécies pertencentes à família Chelidae, ocágado-preto Acanthochelys spixii (Duméril& Bibron, 1835) (N = 16), o cágado-de-pes-coço-de-cobra Hydromedusa tectifera Cope,1870 (N = 11) e o cágado-cinza Phrynopshilarii (Duméril & Bibron, 1835) (N = 44)(FIGURA 2). A abundância relativa dessasespécies foi diferente nas três áreas de cole-ta (FIGURA 3).

A espécie Trachemys dorbigni foi a mais abun-dante (66% das capturas). Foi encontrada nastrês áreas, ocupando diferentes tipos de hábi-tats, desde ambientes permanente ou tempo-rariamente encharcados, até ambientes forte-mente antropizados como canais de esgoto ede drenagem de água das plantações de arroze cavas (TABELA 1).

Acanthochelys spixii representou 8% das cap-turas. A espécie não foi registrada nos canais,sacos e rios amostrados, bem como não foicapturada na IP (TABELA 1). Este cágado foiregistrado apenas em hábitats de águas lênti-

Figura 3: Proporção das quatro espécies de tartarugas de água doce capturadas na Ilha da Pintada, na Ilha das Flores e naFazenda Kramm, no Parque Estadual Delta do Jacuí, RS – Brasil. O número total de indivíduos capturados está entre parênte-ses. Ph = Phrynops hilarii, Ht = Hydromedusa tectifera, As = Acanthochelys spixii e Td = Trachemys dorbigni.

51Artigos Técnico-Científicos Natureza & Conservação - vol. 6 - nº2 - Outubro 2008 - pp. 47-60

Quelônios do delta do Rio Jacuí, RS, Brasil: uso de hábitats e conservação

Figura 2: Espécies de quelônios do Parque Estadual Delta do Jacuí, RS – Brasil: a tartaruga-tigre-d’água Trachemys dorbigni(a), o cágado-preto Acanthochelys spixii (b), o cágado-de-pescoço-de-cobra Hydromedusa tectifera (c) e o cágado-cinzaPhrynops hilarii (d).

A B

C D

0 0,1 0,2 0,3 0,4 0,5 0,6 0,7 0,8 0,9

Capturas proporcionais

Espé

cies

Td

As

Ht

PhIlha Pintada (N = 69)

Ilha Flores (N = 65

Fazenda Kramm (N= 74)

52Artigos Técnico-Científicos Natureza & Conservação - vol. 6 - nº2 - Outubro 2008 - pp. 47-60

Clóvis Souza Bujes - Laura Verrastro

cas, como banhados temporários, canais de ir-rigação, quadras de arroz, cavas e poças dasáreas FK e IF.

Os exemplares de Hydromedusa tectifera foramcapturados nas áreas da IP, FK e IF e consti-tuíram 5% do total de capturas. Não foramcoletados em hábitats de sacos e rios. Foramencontrados em ambientes de águas compouco fluxo e, em sua maioria, de carátertemporário, salvo um exemplar que foi cap-turado no canal da Ilha Pintada/Mauá.

Phrynops hilarii (Figura 3.3D) foi a segunda es-pécie mais abundante. Foi encontrada nasáreas da IP, FK e IF, contribuindo com 21%das capturas. Esta espécie esteve presente emtodos os hábitats amostrados, ocupando am-bientes comuns à espécie T. dorbigni.

Os hábitats preferencialmente ocupados pe-los quelônios foram rios, sacos e canais (decaráter permanente), canais de irrigação dearroz, poças e cavas (de caráter provisório).Imagens representativas desses hábitats sãomostradas na FIGURA 4.

As ameaças mais perceptíveis à fauna e florado PEDJ, incluindo os quelônios, e algumasmedidas que podem ajudar a minimizar osimpactos negativos, são apresentadas e discu-

tidas na TABELA 2. De forma global obser-vou-se que, na maioria dos casos, medidascomo conscientização/educação, vigilância eresponsabilização legal minimizariam ou re-solveriam tal problemática.

DISCUSSÃO

Os Testudines representam a maior biomassados ecossistemas de água doce (Bury, 1979;Souza & Abe, 1997, 2000) e sua distribuição ecomposição das comunidades nos ambientesfluviais são afetadas tanto pelos componentesbióticos, quanto pelos abióticos, muitas vezesligados diretamente à vegetação ciliar(Acuña-Mesen et al.,1983), à competição co-específica, à predação e à temperatura (Moll& Moll, 2004).

Existe pouca informação biológica in situ(Richard, 1999) acerca da maioria das espéciesde tartarugas de água doce da América do Sul.No Brasil, segundo a SBH (2007), são 36 espé-cies de Testudines distribuídas em oito famí-lias. No estado do Rio Grande do Sul, são on-ze espécies de quatro famílias: cinco espécies(duas famílias) marinhas e 6 espécies (2 famí-lias) de ambiente límnico (Lema, 1994). Assim,o número de espécies listadas neste trabalho,para o PEDJ, representa mais de 65% da faunade quelônios de água doce do Rio Grande do

TABELA 1: Distribuição e número de espécimes capturados nos ambientes aquáticos permanentes1 e temporários ou efême-ros2, categorizados para o Parque Estadual Delta do Jacuí – RS, Brasil.

Ambientes/Espécies T. dorbigni A. spixii H. tectifera P. hilarii1Banhados 52 6 5 261Canais 53 0 1 101Sacos 0 0 0 01Rios 5 0 0 12Canais de irrigação 12 2 1 32Quadras de arroz 2 1 1 12Poças 12 5 2 22Cavas 1 2 1 1

N Total 137 16 11 44

53Artigos Técnico-Científicos Natureza & Conservação - vol. 6 - nº2 - Outubro 2008 - pp. 47-60

Quelônios do delta do Rio Jacuí, RS, Brasil: uso de hábitats e conservação

Sul. Os trabalhos de inventário de répteis naárea do PEDJ (relatório técnico não publicadorealizado como parte do subprojeto Consoli-

dação do PEDJ) haviam registrado somenteduas espécies de Testudines: Trachemys dorbignie Phrynops hilarii.

Figura 4: Hábitats utilizados pelos quelônios do Parque Estadual Delta do Jacuí, RS – Brasil. Os hábitats permanentes: rio (a),saco (b) e canal (c); e, os temporários ou efêmeros: canal de irrigação (d), poça (e) e cava (f).

A

D

B

E

C

F

Tabela 2: Principais ameaças observadas sobre os quelônios do Parque Estadual Delta do Jacuí, RS – Brasil, e algumas reco-mendações ou medidas paliativas para minimizar os impactos.

Ameaças

� Incêndios como os ocorridos no ano de 2004 nas ilhasdos Marinheiros e Flores afetaram toda a área de nidifi-cação de quelônios. Na época, suspeitava-se de que aprópria população criava focos de incêndio nas áreasabertas e nos banhados em época de seca, obtendo, as-sim, maiores áreas de pastagem, através da retirada(“limpeza”) da vegetação já estabelecida, e dificilmenteconsumida pelo gado, em troca de vegetação nova, maisnutritiva aos animais domésticos.

� Agricultura extensiva e conseqüente fragmentação dohábitat.

� Agricultura intensiva: extração abusiva de água e uso ir-regular de biocidas e fertilizantes

� Áreas de banhados são aterradas para aumentar a áreade construção de casas ou de criação de gado, fato ob-servado na fazenda Kramm, onde campos inundáveis ebanhados foram aterrados com cascas de arroz

� Drenagem de áreas alagadas ou mesmo períodos muitoprolongados de seca, além de diminuir atividade podeocasionar a morte de indivíduos e dessecamento de ovosnos ninhos

Recomendações ou medidas paliativas

� Conscientização e educação do público em geral so-bre alterações prejudiciais ao ambiente; melhoria dostrabalhos de vigilância tanto no interior do parque co-mo em sua área de entorno e apuração dos responsá-veis pelo dano ambiental e estrita aplicação das medi-das legais.

� Criação de áreas de especial interesse à fauna e flora,mesmo no interior do parque que se mantenham into-cáveis, intensificando a fiscalização nestas áreas

� Intensificar a fiscalização e fazer valer a legislaçãobrasileira vigente

� Intensificar a fiscalização e fazer valer a legislaçãobrasileira vigente

� Orientar as pessoas acerca do uso correto da terra;conscientização do público em geral sobre alteraçõesprejudiciais ao ambiente.

Continua

54Artigos Técnico-Científicos Natureza & Conservação - vol. 6 - nº2 - Outubro 2008 - pp. 47-60

Clóvis Souza Bujes - Laura Verrastro

Todas as tartarugas do Rio Grande do Sul sãoaquáticas e sua distribuição geográfica estágeralmente limitada pela presença de água emambientes permanentes ou sazonais. Os am-bientes fluviais são ecossistemas dinâmicos ediversificados, compostos de uma variedadede hábitats incluindo canais principais,

afluentes, planícies de inundação e lagos.Segundo Moll & Moll (2004), cada hábitat po-de conter uma determinada comunidade dequelônios. Mesmo que as espécies possamaparecer em qualquer lugar do ecossistemafluvial, muitas se especializam em um oumais hábitats onde ocorrem em número e bio-

Continuação Tabela 2

Ameaças

� Construção de trapiches e verticalização das margensatravés de paredes de contenção de água que evita apassagem de animais com hábitos semi-aquáticos

� Eutrofização por criação intensiva de gado ou por despe-jo de resíduos orgânicos

� Eliminação da mata ciliar

� Animais como cães que rondam áreas de nidificação, es-cavando ninhos e consumindo ovos e filhotes, fatos tam-bém observados no Paquistão (Akbar et al., 2006), ondeos cães capturavam tartarugas adultas em águas rasas

� Introdução de espécies exóticas na área do Parque (e.g.mexilhão-dourado Limnoperna fortunei – Manssur et al.,2003 )

� Coleta de exemplares, principalmente neonatos, para co-mercialização e criação como animal de estimação e/outerrariofilia

� Atropelamento nas estradas, principalmente durante operíodo reprodutivo (machos migrando à procura de fê-meas, fêmeas adultas ovígeras a procura de local de nidi-ficação), movimentação de indivíduos entre áreas alaga-das e dispersão de indivíduos jovens

� Muitas vezes fêmeas ovígeras foram maltratadas por hu-manos com pauladas e pedradas

� Utilização de exemplares para consumo da carne e ovosocorrendo principalmente sobre as espécies T. dorbigni eP. hilarii. A coleta de tartarugas para consumo pela po-pulação humana na região do Delta é esporádico e opor-tunista. Algumas P. hilarii fêmeas são apanhadas quandoem atividade de nidificação neste caso são consumidoscarne e ovos

� Comercialização de filhotes, principalmente da tartaruga-tigre-d’água

Recomendações ou medidas paliativas

� Criação de obras adequadas ou adaptadas às áreasalagáveis, que permitam o acesso dos animais àsáreas de água e de terra (acesso à nidificação e à dis-persão de espécimes).

� Controle rigoroso da qualidade da água e do corretotratamento de resíduos

� Estudos de impacto ambiental; regeneração da vege-tação ciliar autóctone.

� Manter animais domésticos presos, e não soltos nasáreas de banhados e/ou de nidificação

� Monitorar e controlar a possível população dessas es-pécies: avaliação da competição interespecífica; cons-cientização do público em geral; campanhas de erra-dicação da espécie introduzida

� Conscientização e orientação ao público em geral;aplicação e fiscalização das leis

� Colocação de redutores de velocidade nas estradas;construção de passadiços subterrâneos nas áreas demaior incidência de atropelamentos

� Informar e conscientizar as pessoas sobre como con-viver com animais que não causam danos aos sereshumanos

� Estudos de monitoramento sobre o consumo da faunasilvestre por população humana; monitorar as popula-ções a médio e longo prazo; conscientização do públi-co em geral sobre a importância da preservação dasespécies

� Orientação e conscientização do público em geral,aplicação e fiscalização das leis

55Artigos Técnico-Científicos Natureza & Conservação - vol. 6 - nº2 - Outubro 2008 - pp. 47-60

Quelônios do delta do Rio Jacuí, RS, Brasil: uso de hábitats e conservação

massa mais elevados. Desta forma, os várioshábitats de um sistema fluvial podem ter com-posição de espécies similares, mas o status deabundância de cada espécie será diferente.

Moll & Moll (2004) verificaram que em 14 de19 comunidades de tartarugas neotropicais,as duas espécies mais abundantes compreen-dem mais de 75% do número de capturas.Entre as quatro espécies, T. dorbigni foi a maisabundante (66 % das capturas) seguida de P.hilarii (21% das capturas), corroborando as-sim o postulado por aqueles autores. Tanto T.dorbigni como P. hilarii se comportam comoespécies eurióicas, de hábitos diurnos, facil-mente observadas nos horários mais quentesdo dia, termorregulando sobre materiaisemersos (troncos, vegetação flutuante, ro-chas, entulhos, etc.). Medem (1960), Monteiro& Diefenbach (1987), Molina (1989) e Souza(1999) fizeram observações similares ao estu-darem espécies como P. hilarii e P. geoffroanus.

Moll & Moll (2004) propuseram que, aparen-temente, a coexistência entre duas espécies defamílias diferentes no mesmo hábitat é possí-vel por haver espécies de tartarugas fluviaisespecialistas e facultativas. Os emidídeos(considerados por Moll & Legler, 1971; Moll& Moll, 1990 tartarugas fluviais facultativas)se tornaram dominantes em muitos rios dasregiões do norte do México ao norte daAmérica do Sul porque, à exceção das peque-nas regiões da América Central, não há ne-nhuma tartaruga fluvial especialista compe-tindo por este hábitat. Não poderíamos en-quadrar T. dorbigni e P. hilarii nessa classifica-ção de tartarugas fluviais especialistas ou flu-viais facultativas porque, apesar da visíveldominância de T. dorbigni, ambas foram espé-cies encontradas em todos os pontos amos-trais (TABELA 1) e que ocuparam os mais di-versificados hábitats, tanto os aquáticos per-manentes, quanto os efêmeros.

Em consonância aos dados de Richard (1999),P. hilarii foi encontrada ocupando ambientespermanentemente alagados e, quando presen-tes naqueles que apresentavam caráter tempo-rário, estes sempre tinham relação com hábitats

permanentes localizados nas proximidades.

Hydromedusa tectifera (Chelidae) mostrou gran-de plasticidade comportamental e resistência àsdiferentes condições ambientais: foram encon-trados exemplares nos esgotos da área urbani-zada (Ilha da Pintada), em ambientes que rece-bem aporte de agrotóxicos (Fazenda Kramm) eem locais aparentemente mais preservados (ba-nhado interno da Ilha das Flores). Ribas &Monteiro-Filho (2002) encontraram H. tectifera,bem como P. geoffroanus e P. williamsi Rhodin &Mittermeier 1983 em ambientes com elevadograu de influência antrópica, onde a poluiçãodos rios modifica o ambiente aquático atravésdo maior aporte de material orgânico. SegundoMoll (1980), algumas espécies de Testudines po-dem ser fisiologicamente oportunistas, sendobeneficiadas em virtude de adaptações espe-ciais a ambientes aquáticos com reduzidos ní-veis de oxigênio. Além disso, os resíduos orgâ-nicos constituem uma fonte de alimento extra,uma vez que muitas larvas de insetos que habi-tam ambientes pouco oxigenados são as princi-pais presas desses animais, levando, muitas ve-zes, ao maior tamanho dos indivíduos dessaspopulações (Moll, 1980; Souza & Abe, 2001). Osambientes ocupados por H. tectifera no PEDJ sãosemelhantes aos descritos por Lema & Ferreira(1990), os quais citam que a espécie ocorre emáguas lênticas e em banhados, apesar de seremencontradas por Ribas & Monteiro-Filho (2002)em águas lóticas (riachos e córregos).

No PEDJ, o quelídeo Acanthochelys spixii foi re-gistrado em ambientes de banhados e am-bientes aquáticos efêmeros, como canais de ir-rigação, quadras de arroz, cavas e valas dedrenagem das lavouras de arroz. D’Amato &Morato (1991) reportaram ser bem comum aocorrência dessa espécie em pequenos riachose banhados próximos a áreas residenciais e in-dustriais. Ribas & Monteiro-Filho (2002) rela-taram que no estado do Paraná, A. spixii foiencontrada em terrenos encharcados comabundância de gramíneas e em áreas de inun-dação temporária durante a época das chuvas.

A espécie com menor freqüência de capturasfoi H. tectifera, porém sua ocorrência deu-se

56Artigos Técnico-Científicos Natureza & Conservação - vol. 6 - nº2 - Outubro 2008 - pp. 47-60

Clóvis Souza Bujes - Laura Verrastro

nas três áreas amostradas, enquanto A. spixiiapresentou freqüência de capturas um poucomaior, mas não foi capturada em uma dasáreas. Stone et al. (2005), estudando uma as-sembléia de tartarugas nos Estados Unidos,argumentaram que parte da distribuição oubaixa freqüência de capturas de Kinosternonflavescens pode ter-se dado por um erro amos-tral, já que aquela espécie gasta boa parte deseu tempo estivando ou hibernando em terra.H. tectifera costuma enterrar-se na lama à me-dida que os locais tornam-se secos, comporta-mento também verificado durante o inverno,ressurgindo na primavera (Lema & Ferreira,1990). Esse hábito também foi verificado porBujes (2006, comunicação pessoal) para a es-pécie A. spixii e pode ter colaborado com asbaixas estimativas de freqüência de ocorrênciae abundância relativa de ambas as espécies.

As espécies listadas neste estudo também ocu-param as cavas, um ambiente bastante pecu-liar e resultante da ação antrópica. No PEDJ ascavas são verdadeiras crateras, decorrentes daextração ilegal de areia em uma área deRestinga vizinha à Fazenda Kramm. São am-bientes efêmeros, com água disponível apenasem períodos de chuvas. Esses hábitats tempo-rários parecem disponibilizar maior aporte derecursos alimentares que propiciam condiçõesfavoráveis para o crescimento e a reprodução,fornecendo abrigo e áreas de nidificação às es-pécies (Kennett & Georges, 1990).

Moll & Moll (2004) reportaram que comuni-dades de tartarugas tendem a ser relativa-mente pobres em número de espécies e geral-mente uma ou duas espécies costumam ocor-rer juntas num mesmo hábitat, o que tambémpode ser atribuído à comunidade de quelô-nios do PEDJ.

Com exceção de Acanthochelys spixii que estácategorizada como baixo risco/quase ameaça-da (LR/NT) na lista da IUCN (2006), os quelô-nios do PEDJ não figuram em listas nacionaisde espécies ameaças. No entanto, os impactoscausados pelo desmatamento e pela poluiçãona região do Delta do Jacuí podem representarsérios riscos à sobrevivência daquelas espé-

cies. As ameaças listadas e as situações obser-vadas no PEDJ (TABELA 2) não afetam, obvia-mente, somente os quelônios, mas também asdemais espécies da fauna e flora. A fragilidadedas populações de tartarugas está ligada àsbaixas taxas de recrutamento, baixa densidadepopulacional e à fragmentação do hábitat. Semdúvida, a alteração no hábitat foi a mais graveameaça verificada no PEDJ, o que acarreta naredução ou perda absoluta de ambientes ne-cessários às funções vitais essenciais de muitosorganismos, incluindo alimentação (Vickery etal., 2001), reprodução (Heckert et al., 2003) eabrigo (Ball, 2002). No PEDJ foi observada a re-tirada da vegetação ciliar para construção deresidências e a construção de diques (tapumes)nas margens, visando à contenção da água eimpedindo assim o acesso dos animais às áreasde terras adjacentes para deslocamento e/ounidificação. O aumento da urbanização tem semostrado responsável por mudanças drásticasem muitas populações animais, e.g. grandescarnívoros (Reilly et al., 2003), borboletas(Collinge et al., 2003), salamandras (Willson &Dorcas, 2003), peixes (Paul & Meyer, 2001),bem como em comunidades vegetais, tanto deambientes terrestres (Fransisco-Ortega et al.,2000) quanto em ambientes aquáticos (Fore &Grafe, 2002).

De la Ossa-Velásquez & Fajardo (1998) consi-deraram a destruição e a alteração dos am-bientes naturais a ameaça mais grave para asobrevivência de Phrynops dahli, espécie endê-mica da Colômbia, cujo hábitat desapareceuquase que totalmente como conseqüência daexpansão da fronteira agropecuária e desen-volvimento urbano. O desmatamento da ve-getação ciliar e a conseqüente alteração dasmargens dos rios podem, segundoHildebrand & Muñoz (1992), ter provocado adestruição de todo o esforço reprodutivo dasespécies de quelônios na Colômbia.

Gibbons et al. (2000) consideraram a destrui-ção/fragmentação de hábitats como a ameaçamais grave à biodiversidade, seguida da in-trodução de espécies, poluição ambiental,doenças e parasitismo, uso insustentável emudanças no clima global. Conforme

57Artigos Técnico-Científicos Natureza & Conservação - vol. 6 - nº2 - Outubro 2008 - pp. 47-60

Quelônios do delta do Rio Jacuí, RS, Brasil: uso de hábitats e conservação

Tabarelli et al. (2004), o desmatamento temefeitos diretos e indiretos na redução dos há-bitats das espécies de plantas e animais. Comoexemplo de efeito direto, esses autores citam aeliminação de vertebrados dispersores de se-mentes, comprometendo assim a germinação.Quanto aos indiretos, mencionam a produçãode grandes quantidades de detrito orgânico,que, combinados ao lixo e à biomassa morta,decorrente da fragmentação, deixam certas re-giões ainda mais suscetíveis aos incêndios.Burke et al. (1994) sugeriram que as tartarugaspodem ser especialmente vulneráveis ao de-clínio populacional devido as suas estratégiasreprodutivas incompatíveis com a exploraçãoe significante perda de hábitat.

A educação é uma importante ferramenta pa-ra o desenvolvimento de uma postura queconduza aos projetos de conservação, bem co-mo um elemento-chave no seu sucesso, à me-dida que as pessoas envolvidas ou afetadaspelo programa sejam informadas da necessi-dade daquela ação e dos benefícios do pro-grama para o seu presente e futuro. ParaCongdon et al. (1993), os programas de ma-nejo e conservação de tartarugas bem sucedi-dos seriam aqueles que reconhecem que aproteção se faz necessária em todos os está-gios da história de vida dos organismos.

CONCLUSÃO

A comunidade de quelônios do PEDJ é com-posta por quatro espécies que ocupam diferen-tes tipos de hábitats, incluindo ambientes aquá-ticos permanentes e efêmeros. As ameaças à so-brevivência dessas espécies são muitas e estãointimamente relacionadas à presença humanana área do Parque. Diante das questões apre-sentadas neste estudo, verifica-se a necessidadepremente de conscientização do público sobrea importância dos quelônios e o fato de que oconvívio com eles não causa danos aos sereshumanos. Não obstante, deve-se intensificar afiscalização e aplicação da legislação ambientalvigente, bem como a implementação de estu-dos para a proteção in loco dos animais e dosambientes ocupados por eles.

AGRADECIMENTOS:

Agradecemos à Fundação O Boticário deProteção à Natureza (FBPN, ProjetoChelonia–RS 0594-20032) pelo apoio financei-ro; ao Instituto Gaúcho de EstudosAmbientais (INGA), à Secretaria Estadual doMeio Ambiente (SEMA) e ao Departamentode Zoologia da Universidade Federal do RioGrande do Sul (UFRGS) pelo apoio logístico;e, aos funcionários do Parque Estadual Deltado Jacuí, em especial a Loiva e ao Clemente.Aos colegas Dr. Flávio de Barros Molina e Dr.Márcio Borges Martins, pela valiosa contri-buição na revisão do manuscrito.

REFERÊNCIAS

Accordi, I.A. 2002. Asas do delta: aves entre aterra e água. In: Fundação Zoobotânica doRio Grande do Sul (ed.). Natureza em revista:Delta do Jacuí. Pp. 54-59. Porto Alegre:Fundação Zoobotânica do Rio Grande do Sul.

Acuña-Mesen, R. A.; Castaing, A.; Flores, F.1983. Aspectos ecológicos de la distribuciónde las tortugas terrestres y semiacuáticas en elValle Central de Costa Rica. Revista de BiologiaTropical, 31 (2): 181-192.

Akbar, M.; Hassan, M. M.; Nisa, Z. 2006.Distribution of freshwater turtles in Punjab,Pakistan. Caspian Journal of EnvironmentalSciences, 4 (2): 142-146.

Ball, L. C. 2002. A strategy for describing andmonitoring bat habitat. Journal WildlifeManagement, 66: 1148-1153.

Branco-Filho, C. C.; Basso, L. A. 2005.Ocupação irregular e degradação ambientalno Parque Estadual Delta do Jacuí-RS.Geografia, 30(2): 285-302.

Burke, V. J.; Gibbons, J. W.; Greene, J. L. 1994.Prolonged nesting forays by common mud

58Artigos Técnico-Científicos Natureza & Conservação - vol. 6 - nº2 - Outubro 2008 - pp. 47-60

Clóvis Souza Bujes - Laura Verrastro

turtles (Kinosternon subrubrum). AmericanMidland Naturalist, 131 (1): 190-195.

Bury, R. B. 1979. Population ecology of fresh-water turtles. In: Harless, M; Morlock, H.(ed.). Turtles: perspectives and research. Pp. 571-604. New York: John Wiley.

Cagle, F. R. 1939. A system of marking turtlesfor future identification. Copeia, 1939 (3): 170-173.

Collinge, S. K.; Prudic, K. L.; Oliver, J. C. 2003.Effects of local habitat characteristics land-scape context on grassland butterfly diversity.Conservation Biology, 17: 178-187.

Congdon, J. D.; Dunham, A. E.; Van LobenSels, R.C. 1993. Delayed sexual maturity anddemographics of Blanding’s turtles(Emydoidea blandingii): implications for con-servation and management of long-lived or-ganisms. Conservation Biology, 7: 826-833.

Conner, C. A.; Douthitt, B. A.; Ryan, T. J. 2005.Descriptive ecology of a turtle assemblage inan urban landscape. The American MidlandNaturalist, 153 (2): 428-435.

D’Amato, A. F.; Morato, S. A. A. 1991. Notasbiológicas e localidades de registro dePlatemys spixii (Duméril & Bibron, 1835)(Testudines: Chelidae) para o Estado doParaná, Brasil. Acta Biológica Leopoldensia, 13(2): 119-130.

De la Ossa-Velásquez, J.; Fajardo, A. 1998.Introducción al conocimiento de algunas especiesde fauna silvestre del Departamento de Sucre-Colombia. Sucre: Carsucre Fundación GeorgeDahl.

Fore, L. S.; Grafe, C. 2002. Using diatoms toassess biological condition of large rivers inIdaho (U. S. A.). Freshwater Biology, 47 (10):2015-2037.

Fransisco-Ortega, J.; Santos-Guerra, A.; Kim,S. C.; Crawford, D. J. 2000. Plant genetic di-versity in the Canary Island: a conservation

perspective. American Journal of Botany, 87 (7):909-919.

Garber, S. D.; Burger, J. 1995. A 20-yr studydocumenting the relationship between turtledecline and human recreation. EcologicalApplications, 5: 1151-1162.

Gibbons, J. W.; Scott, E. D.; Ryan, T. J.;Buhlmann, K. A.; Tuberville, T. D.; Metts, B.S.; Geene, J. L.; Mills, T.; Leiden, Y.; Poppy, S.;Winne, C. T. 2000. The global decline of rep-tiles, déjà vu amphibians. BioScience, 50: 653-666.

Gibbs, J. P.; Shriver, W. G. 2002. Estimatingthe effects of road mortality on turtle popula-tions. Conservation Biology, 16 (6): 1647-1652.

Heckert, J. R.; Reinking, D. L.; Wiedenfeld, D.A.; Winter, M.; Zimmerman, J. L.; Jensen, W.E.; Flink, E. J.; Koford, R. R.; Wolfe, D. H.;Sherrod, S. K.; Jenkins, M. A.; Faaborg, J.;Robinson, S.K. 2003. Effects of prairie frag-mentation on the nest success of breedingbirds in the midcontinental United States.Conservation Biology, 17: 587-594.

Hildebrand, P. V.; Muñoz, D. 1992.Conservación y manejo sostenible de la tortu-ga charapa (Podocnemis expansa) en el bajo RíoCaquetá en Colombia. Fase III. Proyecto deInvestigación. 21 pp.

IUCN. 2006. 2006 IUCN Red List of ThreatenedSpecies. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloadedon 23 August 2007.

Kennett, R. M.; Georges, A. 1990. Habitat uti-lization and its relationship to growth and re-production of the eastern long-necked turtle,Chelodina longicollis (Testudinata: Chelidae),from Australia. Herpetologica, 46, (1): 22-33.

Koch, W. R.; Milani, P. C.; Grosser, K. M. 2002.Peixes das chuvas. In: Fundação Zoobotânicado Rio Grande do Sul (ed.). Natureza em revis-ta: Delta do Jacuí. Pp. 52-53. Porto Alegre:Fundação Zoobotânica do Rio Grande do Sul.

59Artigos Técnico-Científicos Natureza & Conservação - vol. 6 - nº2 - Outubro 2008 - pp. 47-60

Quelônios do delta do Rio Jacuí, RS, Brasil: uso de hábitats e conservação

Lema, T. 1994. Lista comentada dos répteisocorrentes no Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil.Comunicações do Museu de Ciências e Tecnologiada PUCRS, Série Zoologia, 7: 41-150.

Lema, T.; Ferreira, M. T. S. 1990. Contribuiçãoao conhecimento dos Testudines do RioGrande do Sul (Brasil) – lista sistemática co-mentada (Reptilia). Acta BiológicaLeopoldensia, 12 (1): 125-164.

Lindsay, S. D.; Dorcas, M. E. 2001. Effects ofcattle on reproduction and morphology ofpond-dwelling turtles in North Carolina. J.Elisha Mitchell Scientific Society, 117: 249-257.

Maluf, J. R. T. 2000. Nova classificação climá-tica do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul. RevistaBrasileira de Agrometeorologia, 8 (1): 141-150.

Medem, F. 1960. Informe sobre reptiles co-lombianos (V). Observaciones sobre la distri-bución geográfica y ecología de la tortugaPhrynops geoffroana ssp. en Colombia.Novedads Colombianas, 1: 291-300.

Melo, M. T. Q. 2002. Rãs, sapos e pererecas. In:Fundação Zoobotânica do Rio Grande do Sul(ed.). Natureza em revista: Delta do Jacuí. Pp. 54-59. Porto Alegre: Fundação Zoobotânica doRio Grande do Sul.

Mitchell, J. C. 1988. Population ecology andlife histories of the freshwater turtlesChrysemys picta and Sternotherus odoratus inan urban lake. Herpetological Monographs, 2(1988): 40-61.

Molina, F. B. 1989. Observações sobre a biologia eo comportamento de Phrynops geoffroanus(Schweigger, 1812) em cativeiro (Reptilia,Testudines, Chelidae). Dissertação de Mestradonão-publicada. Universidade de São Paulo,Brasil.

Moll, D. 1980. Dirty river turtles. NaturalHistory, 89 (5): 43-49.

Moll, D.; Moll, E. 1990. The slider turtle in theNeotropics: adaptations of a temperate

species to a tropical environment. In:Gibbons, J. W. (ed.). Life history and ecology ofthe slider turtle. Pp. 152-161. Washington D. C.:Smithsoniam Institution Press.

Moll, D.; Moll, E. O. 2004. The ecology, ex-ploitation and conservation of river turtles. NewYork: Oxford University Press. 393 p.

Moll, E. O.; Legler, J. M. 1971. The life historyof a neotropical slider turtle Pseudemys scripta(Schoepff) in Panama. Bulletin of the LosAngeles Country Museum of the Natural HistoryScience, 11: 1-102.

Monteiro, L. P.; Diefenbach, C. O. C. 1987.Thermal regime of Phrynops hilarii (Reptilia,Chelonia). Boletim de Fisiologia Animal, SãoPaulo 11: 41–50.

Oliveira, M. L. A. A. 1998. Análise do padrão dedistribuição espacial de comunidades vegetais doParque Estadual Delta do Jacuí: Mapeamento esubsídios ao zoneamento da unidade de conserva-ção. Tese (Doutorado em Ciências) – Curso dePós-graduação em Botânica, UniversidadeFederal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre.234 p.

Oliveira, M. L. A. A. 2002. Conhecendo oParque. In: Fundação Zoobotânica do RioGrande do Sul (ed.). Natureza em revista: Deltado Jacuí. Pp. 12-19. Porto Alegre: FundaçãoZoobotânica do Rio Grande do Sul.

Paul, M. J.; Meyer, J. L. 2001. Streams in theurban landscapes. Annual Review of Ecologyand Systematics, 32: 333-365.

Reilly, S. P. D.; Sauvajot, R. M.; Fuller, T. K.;York, E. C.; Kamradt, D. A.; Bromley, C.;Wayne, R. K. 2003. Effects on urbanizationand habitat fragmentation on bobcats andcoyotes in southern California. ConservationBiology, 17: 566-576.

Ribas, E. R.; Monteiro-Filho, E. L. A. 2002.Distribuição e habitat das tartarugas de água-doce (Testudines, Chelidae) do estado doParaná, Brasil. Biociências, 10 (2): 15-32.

60Artigos Técnico-Científicos Natureza & Conservação - vol. 6 - nº2 - Outubro 2008 - pp. 47-60

Clóvis Souza Bujes - Laura Verrastro

Richard, E. 1999. Tortugas de las regiones áridasde Argentina. Buenos Aires: Literature of LatinAmerica (LOLA).

Rodrigues, M. T. 2005. The Conservation ofBrazilian Reptiles: Challenges for aMegadiverse Country. Conservation Biology,19 (3): 659-664.

Rubin, C. S.; Warner, R. E.; Bouzat, J. L.; Paige,K. N. 2001. Population genetic structure ofBlanding’s turtle (Emydoidea blandinggii) in anurban landscape. Biological Conservation, 99:323-330.

Rylands, A. B.; Brandon, K. 2005. Brazilianprotected areas. Conservation Biology, 19: 612-618.

SBH. 2007. Lista de espécies de répteis do Brasil.Sociedade Brasileira de Herpetologia (SBH).Disponível em: http://www2.sbherpetologia.org.br/checklist/repteis.htm, acessado em 8de outubro 2007.

Souza, F. L. 1999. Ecologia do cágado Phrynopsgeoffroanus (Schweigger, 1812) em ambiente ur-bano poluído (Reptilia, Testudines, Chelidae).Tese de Doutorado não-publicada. Universi-dade Estadual Paulista, Rio Claro, Brasil.

Souza, F. L.; Abe, A. S. 1997. Population struc-ture, activity, and conservation of theneotropical freshwater turtle, Hydromedusamaximiliani, in Brazil. Chelonian Conservationand Biology, 2 (4): 521-525.

Souza, F. L.; Abe, A. S. 2000. Feeding ecology,density and biomass of the freshwater turtle,Phrynops geoffroanus, inhabiting a polluted ur-ban river in south-eastern Brazil. Journal ofZoology, 252: 437-446.

Souza, F. L.; Abe, A. S. 2001. Population struc-ture and reproductive aspects of the freshwaterturtle, Phrynops geoffroanus, inhabiting an urbanriver in Southeastern Brazil. Studies onNeotropical Fauna and Environment, 36 (1): 57-62.

Stone, P. A., Powers, S. M.; Babb, M. E. 2005.

Freshwater turtles assemblages in CentralOklahoma farm ponds. The SouthwesternNaturalist, 50 (2): 166-171.

Tabarelli, M.; Silva, J. M. C.; Gascon, C. 2004.Forest fragmentation, synergisms and the im-poverishment of neotropical forests. Biodiver-sity and Conservation, 13: 1419-1425.

Thorbjarnarson, J.; Lagueux, C. J.; Bolze, D.;Klemens, M. W.; Meylan, A. B. 2000. Humanuse of turtles: a worldwide perspective. In:M.W. Klemens (ed.). Turtle Conservation. Pp.33-84. Washington D. C.: SmithsonianInstitute Press.

Turtle Conservation Fund. 2002. A global ac-tion plan for conservation of tortoises andfreshwater turtles. Strategy and fundingprospectus 2002-2007. Conservation Internationaland Chelonian Research Foundation. Washing-ton, D.C. 30 pp.

Vickery, J .A.; Tallowin, J. R.; Feber, R. E.;Asteraki, E. J.; Atkinson, P. W.; Fuller, R. J.;Brown, V. K. 2001. The management of low-land neutral grassland in Britain: effects ofagricultural practices on birds and their foodresources. The Journal of Applied Ecology, 38:647-664.

Willson, J. D.; Dorcas, M. E. 2003. Effects ofhabitat disturbance on stream salamanders:implications for buffer zones and watershedmanagement. Conservation Biology, 17: 763-771.

154Technical – Scientific Articles Natureza & Conservação - vol. 6 - n.2 - October 2008 - pp. 141-156

Fabiana Cézar Félix-Hackradt - Carlos Werner Hackradt

fishes of south-central Florida. Northeast GulfScience 2(2): 77-97.

Hostim-Silva, M., Bertoncini, A. A.;Gerhardinger, L. C.; Machado, L. F. 2005. TheLord of the Rocks conservation program inBrazil: the need for a new perception of ma-rine fishes. Coral Reefs, 24: 74.

Karmann, I.; Dias Neto, C. M.; Weber, W.1999. Caracterização litológica e estruturaldas rochas sedimentares do conjunto insularCardoso, sul do Estado de São Paulo. RevistaBrasileira de Geociências, 29 (2):157-162.

Koenig, C. C.; Coleman, F. C. 1998. Absoluteabundance and survival of juvenile gags insea grass beds of the northeastern Gulf ofMexico. Transactions of American FisheriesSociety 127: 44–55.

Koenig,C. C.; Coleman, F. C.; Eklund, A. M.;Schull, J.; Ueland, J. 2007. Mangroves as es-sential nursery hábitat for goliath groupes(Epinephelus itajara). Bulletin of Marine Science80(3): 567–586.

Lana, P. C.; Marone, E.; Lopes, R. M.; Machado,E. C. 2001. The subtropical estuarine complexof Paranaguá Bay, Brazil. In: Seeliger, U. &Kjerfe, B. Coastal marine ecosystems of LatinAmerica. Springer Verlag, Berlin. Pp. 131-145.

Lorenz, K. 1995. Os fundamentos da etologia.Editora da Universidade Estadual Paulista,São Paulo. 147p.

Murawski, S. A.; Wigley, S. E.; Fogarty, M. J.;Rago, P. J.; Mountain, D. G. 2005. Effort dis-tribution and catch patterns adjacent to tem-perate MPAs. ICES Journal of Marine Science62: 1150-1167.

NMFS. 2006. Status report on the continentalUnited States distinct population segment ofthe goliath grouper (Epinephelus itajara). 49 p.

Pikitch E. K.; Santora C.; Babcock E. A.;Bakun A.; Bonfil, R.; Conover, D. O.; Dayton,P.; Doukakis, P.; Fluharty, D.; Heneman, B.;

Houde, E. D.; Link, J.; Livingston, P. A.;Mangel, M.; McAllister, M. K.; Pope, J.;Sainsbury, K. J. 2004. Ecosystem-based fish-ery management. Science 305: 346–347.

Porch, E. C.; Ecklund, A. M. 2003.Standardized visual counts of goliath grouper offsouth Florida and their possible use as indices ofabundance. SEDAR6, Review 1. SustainableFisheries Division Contribution. 23p.

Primack, R. B.; Rodrigues, E. 2001. Biologia daConservação. Editora Vozes, Curitiba. 327p.

Roberts, C. M. 1995. Rapid Build-up of FishBiomass in a Caribbean Marine Reserve.Conservation Biology 9(4): 815-826.

Russ, G. R.; Stockwell, B.; Alcala, A. C. 2005Inferring versus measuring rates of recoveryin no-take marine reserves. Marine EcologyProgress Series 292: 1-12.

Sadovy, Y.; Eklund, A. M. 1999. Synopsis ofbiological data on the Nassau grouper,Epinephelus striatus (Bloch, 1792), and thejewfish, E. itajara (Lichtenstein, 1822).NOAA Technical Report NMFS 146. 65p.

Sale, P. F. (ed.) 2002. Coral Reef Fishes:Dynamics and Diversity in a ComplexEcosystem. Academic Press, San Diego. 549p.

SEDAR, SouthEast Data, Assessment, andReview. 2004. Complete Stock AssessmentReport of SEDAR 6, Gouliath Grouper. FloridaFish and Wildlife Commission’s FloridaMarine Research Institute (FWC-FMRI),Charlestone. 127p.

Silva, A. S. 2001. Estrutura e dinâmica de co-munidades epilíticas de hábitats artificiais e suasrelações com os fatores ambientais na plataformarasa do Estado do Paraná. Tese de Doutorado,Departamento de Zoologia, UniversidadeFederal do Paraná. 166p.

Smith, G. B. 1976. Ecology and distributionof eastern Gulf of Mexico reef fishes. FloridaMarine Research Publications, No. 19. 78p.

155Technical – Scientific Articles Natureza & Conservação - vol. 6 - n.2 - October 2008 - pp. 157-170

Chelonians from the Delta of Jacuí River, RS, Brazil: habitats use and conservation

INTRODUCTION

Protected areas assure, at first, the preserva-tion of species within them; however, they aresubject to wild fires and other difficult to no-tice threats. Thus, depending on its size andlocation, the extinction of at least a small partof their species is inevitable (Rodrigues,2005). In Brazil, state, federal, and indigenouslands that are protected areas make up ap-proximately 23% of the country’s territory(Rylands & Brandon, 2005) and these areasare extremely important for the conservationof fauna and flora species. Brazilian laws de-vised a National Protected Areas Systemwhich, among other attributions, establishesthe creation of Environmental ProtectionAreas (EPA) and Parks. The Parks basically

aim at the preservation of natural ecosystemsof great ecological relevance and scenic beau-ty, allowing the execution of scientific re-searches and the development of environ-mental education and interpretation activi-ties, and recreation in contact with nature andecological tourism. The EPAs are usuallylarge areas, with a certain degree of humanoccupation, endowed with esthetic and cul-tural attributes that are especially importantfor the quality of life and welfare of humanpopulations. According to Act 9985, passedon July 18, 2000, they basically aim at protec-ting biological diversity, to discipline the oc-cupation process and to ensure the sustain-ability in the use of natural resources.

The Delta do Jacuí State Park was establishedin 1976 and has been historically sufferingfrom irregular settlements and environmentaldegradation. The Delta of the Jacuí River has

Engl

ish

Chelonians from the Delta of Jacuí River, RS,Brazil: habitats use and conservation

Clóvis Souza Bujes, Dr1

• Post-grade Program in Animal Biology – Department of Zoology, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRS)Laura Verrastro, Drª• Post-grade Program in Animal Biology – Department of Zoology, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRS)

ABSTRACT. The inventory performed in the Delta do Jacuí State Park, aiming at knowing the che-lonian fauna, its habitat, and the main threats to the species, has presented the occurrence of a speciesbelonging to the Emydidae family, Trachemys dorbigni, the Orbigny’s slider (Duméril & Bibron, 1835),and three species belonging to the Chelidae family: the spine-necked turtle, Acanthochelys spixii(Duméril & Bibron, 1835), the South American snake-necked turtle, Hydromedusa tectifera (Cope,1870), and the Hilaire’s side-necked turtle, Phrynops hilarii (Durémil & Bibron, 1835). The Orbigny’sslider was the most abundant, making up over 66% of the captured specimens. The Hilaire’s side-necked turtle made up 21% of the captured specimens, the spine-necked turtle 8%, and the SouthAmerican snake-necked turtle counted 5% of the captured specimens. The species occupied differenttypes of habitat, classified in this work as marshes, channels, sacks, rivers, irrigation channels, ricepaddies, puddles, and water holes. The destruction and fragmentation of habitat, pollution and dis-information by human populations were the main threats to chelonians in the Park.

Keywords: Testudines, human occupation, anthropic changes, conservationist education

156Technical – Scientific Articles Natureza & Conservação - vol. 6 - n.2 - October 2008 - pp. 157-170

Clóvis Souza Bujes - Laura Verrastro

gone through profound changes over the lastfifty years, due to the economic decline infishing activities, navigation, and small dairyand agricultural production. Besides, thedeposition of residues and effluents origina-ting from tanning industries in the Rio dosSinos valley contribute for pollution of a greatpart of the waters surrounding the islands(Branco-Filho & Basso, 2005).

Located in the Metropolitan Area of PortoAlegre, where the rivers Jacuí, Gravataí, Caí,and Sinos meet, the Park is composed of 30 is-lands and continental land covered withwoods, marshes, and flooded fields. It is oneof the most important wetlands in the state ofRio Grande do Sul, integrating a mosaic ofecosystems that represent an ecotone or tran-sition between the higher areas belonging tothe Central Depression and the CoastalLagoon System (Oliveira, 2002). Human oc-cupation, which began in the 18th Century,has generated a population that lives alongthe area’s rich biological diversity: approxi-mately 78 fish species (Koch et al., 2002), 24amphibian species (Melo, 2002), 210 birdspecies (Accordi, 2002), as well as endangeredspecies such as the broad-snouted caiman(Caiman latirostris) and the Geoffroy’s cat(Oncifelis geoffroyi).

Turtle populations in many parts of the worldare strongly impacted by human activities,development and urbanization. Approxi-mately two thirds of terrestrial and fresh-wa-ter turtle species in the world are listed asthreatened by the IUCN and over a third hasnot been evaluated yet (Turtle ConservationFund, 2002). Human exploitation of chelo-nian species has caused the decline of manypopulations, local extermination and even theextinction of species (Thorbjarnarson et al.,2000). Several papers mention human actionsas the main factor behind habitat destructionand fragmentation (e.g., Gibbons et al., 2000).Among the negative effects, are the fragmen-tation of genetic structure (Rubin et al., 2001),demographic consequences (Garber & Bur-ger, 1995; Lindsay & Dorcas, 2001), and mor-tality rates (e.g., by being run over by vehi-

cles, Gibbs & Shriver, 2002). However, somechelonian species can be very resilient to hu-man activities and continue to thrive in high-ly modified environments, while other wildanimals disappear (Mitchell, 1988).

Descriptive data on the status of populationsand communities might serve as a startingline for future enquires in the effects of ur-banization on organisms, so that efforts canbe thus directed into conservation of speciesand the environments they inhabit (Conneret al., 2005). In face of this fact, the presentstudy proposes the following: (1) get toknow the turtle species that occur in theDelta do Jacuí State Park; (2) describe thehabitats they occupy; and (3) identify poten-tial threats in an environment that is strong-ly changed by man.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Delta do Jacuí State Park (DJSP) is a pro-tected area located in the mid-eastern regionof the state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil(29º53’, 30º03’ S; 51º28’, 51º13’ W). The DJSPhas an area over 21,000 hectares, includingcontinental lands and 30 islands (Oliveira,2002). According to Maluf (2000), the state ofRio Grande do Sul is located in an intermedi-ary area climate-wise, between the Temperate(presenting an average temperature of 13ºCduring the coldest month) and Subtropical(presenting average temperatures between 15and 20ºC during the coldest month).According to the author, the area of studypresents climate type ST UMv (Subtropicalwith humid summers), and its average annu-al temperature is 19ºC, and an average tem-perature of 14ºC during the coldest month; apluvial precipitation of 1,309 mm, annual hy-dric deficit of 50 mm, and annual hydric ex-cess of 210 mm. The hydric regimen alter-nates drought and flooded periods, forcingthe vegetation to adapt to these conditions.Thus the remarkable presence of marshes,herein considered as permanent or temporarybodies of water, without a well determinedbasin, with indefinite contours and perimeter,and without their own sediments, presenting

157Technical – Scientific Articles Natureza & Conservação - vol. 6 - n.2 - October 2008 - pp. 157-170

Chelonians from the Delta of Jacuí River, RS, Brazil: habitats use and conservation

abundant emerging vegetation and few openspaces (Ringuelet, 1962 apud Oliveira, 1998).Marshes present vegetation formations dom-inated by the sarandi-branco Cephalanthusglabratus (Rubiaceae), the Alligator Flag Thaliageniculata (Marantaceae), the amyrucaPsychotria carthagenensis (Rubiaceae), the es-padana Zizaniopsis bonariensis (Poaceae), the er-va-de-bicho Polygonum stelligerum (Polygonaceae),as well as a multitude of macrophytes such asthe Anchored water hyacinth Eichornia azurea(Pontederiaceae) and the elephant panicgrassPanicum elephantipes (Poaceae) which developon the banks of the sacks, the channels be-tween islands, the islands, where the currentis not strong (Oliveira, 1998).

Regarding water courses, this study took intoconsideration two types of environment: (1)permanent and (2) temporary. Permanentrefers to all environments that are kept floo-ded even during droughts, such as: densely

wooded internal marshes, channels (naturalor man-made courses of water, in which wa-ter moves connecting two bodies of water),sacks (a semi-closed environment connectedto the river by a narrow channel), and rivers.Temporary refers to all the bodies of waterthat suffer great volume oscillations, and thatin the majority of times completely dry overshort periods of time: irrigation channels(used for water transportation from the mainchannels to the rice paddies), rice paddies(environments that are similar to secondarychannels regarding water flow but usuallyshallower), puddles (small field areas thatflooded during the raining season), and waterholes (areas of sand extraction near marshesand rivers).

The chelonians were collected in three sitesinside the DJSP (FIGURE 1). The first site, theproject’s base, is located in the Pintada Island(IP). The chelonian study area was of

Engl

ish

Figure 1: Location of the Delta do Jacuí State Park, RS – Brazil and the sites of collection in the Fazenda Kramm (FK), FloresIsland (IF), and Pintada Island (IP).

Jacui River

Cai River

Sinos River

Gravatai River

PORTO ALEGRE

SouthAmerica

Argentina

Uruguay

Rio Grande do Sul

BRAZIL

158Technical – Scientific Articles Natureza & Conservação - vol. 6 - n.2 - October 2008 - pp. 157-170

Clóvis Souza Bujes - Laura Verrastro

approximately three hectares, an urban areathat included, at its center, the Mauá channel;to the north of the channel, there is a largeworking shipyard; to the south, the yard ofthe DJSP headquarters (used by the turtles asa nesting site); to the west, human edifica-tions (houses, commerce, schools) on marshesbanks and over them; and, to the east, theJacuí river (30°01’52”S, 51°15’07”W). The sec-ond site, the Fazenda Kramm (FK), is a farm-ing property located on the boundaries of theDJSP, south of the Jacuí River, in front of theCravo and Cabeçudas islands. The approxi-mately nine hectares area used for data col-lection includes marshes, rice paddies andwater holes (craters originating from illegalsand extraction) in an area of marsh vegeta-tion, next to the farm (29°58’59”S,51°18’58”W). The third site is located in theFlores Island (IF), in a six hectares area thatincludes marshes and a road (in whose banksthe chelonians nest) 200 meters from theEastern bank of the Jacuí River (29°58’48”S,51°16’22”W). The IP site is located 8.5 kilome-ters away from FK, which is located 5.3 kilo-meters away from the IF site, which, in turn,is located 5.2 kilometers away from the IPsite.

The expeditions took place from September2003 to August 2004 at the IP site; fromSeptember 2004 to August 2005 at the FK site;and from September 2005 to August 2006 atthe IF site. The sampling effort took two tothree consecutive days per week, betweenSeptember and January, and one day a weekduring the other months. In all areas, the cap-tures were manually made and using six box-traps (600 mm X 306 mm X 800 mm), whichused chicken carcasses as bait. The traps weresemi-submersed placed, at a 40-meters dis-tance from each other, along the banks and re-mained in the site for at least 24 hours. Thetraps were revised each three hours and, ateach expedition, their location was changed,aiming at the maximization of the coverage ofeach area.

After the identification, weighing, and gath-ering of biometric data were performed, each

captured turtle was individually markedwith a carving on their side shell (Cagle, 1939)and later released on the same capture site.The gender of adults was determined fromsecondary sexual characteristics, that is, posi-tioning of the cloaca in relation to the posteri-or margin of the plastron, the existence ofcavities on the plastron, and occurrence ofmelanization process.

Considerations about the threats to thespecies and their habitats in the DJSP, dis-cussed in this study were done from directobservations in the environment and throughinformal interviews with local human popu-lations.

RESULTS

208 specimens belonging to four fresh-waterchelonian species were captured: one speciesbelonging to the Emydidae family, theOrbigny’s slider Trachemys dorbigni (Duméril& Bibron, 1835) (N=137), and three speciesbelonging to the Chelidae family, the spine-necked turtle, Acanthochelys spixii (Duméril &Bibron, 1835) (N=16), the South Americansnake-necked turtle, Hydromedusa tectifera(Cope, 1870) (N=11), and the Hilaire’s side-necked turtle, Phrynops hilarii (Durémil &Bibron, 1835) (N=44) (FIGURE 2). The rela-tive abundance of these species was differentin the three collection sites (FIGURE 3).

The Trachemys dorbigni species was the mostabundant (66% of the captures). It was foundin the three areas, occupying different typesof habitats, from permanently or temporarilywet environments to environments stronglyinfluenced by human activity, such as sewerand water drainage channels in rice planta-tions and water holes (TABLE 1).

The Acanthochelys spixii represented 8% of thecaptures. The species was not recorded in thesampled channels, sacks and rivers, and itwas not captured at the IP site either (TABLE1). This turtle was recorded only in lentic wa-ter environments, such as temporary mar-shes, irrigation channels, rice paddies, water

159Technical – Scientific Articles Natureza & Conservação - vol. 6 - n.2 - October 2008 - pp. 157-170

Chelonians from the Delta of Jacuí River, RS, Brazil: habitats use and conservation

Engl

ish

Figure 3: The rate of the four fresh-water turtle species captured in the Pintada Island, in the Flores Island, and in the FazendaKramm, in the Delta do Jacuí State Park, RS – Brazil. The total number of captured individuals is between brackets. Ph =Phrynops hilarii, Ht = Hydromedusa tectifera, As = Acanthochelys spixii, and Td = Trachemys dorbigni.

Figure 2: Chelonian species of the Delta do Jacuí State Park, RS – Brazil: the Orbigny’s slider Trachemys dorbigni (a), the spine-necked turtle, Acanthochelys spixii (b), the South American snake-necked turtle, Hydromedusa tectifera (c), and the Hilaire’sside-necked turtle, Phrynops hilarii (d).

A B

C D

0 0,1 0,2 0,3 0,4 0,5 0,6 0,7 0,8 0,9

Proportional Captures

Spe

cies

Td

As

Ht

PhPintada Island (N =

Flores Island (N = 65

Fazenda Kramm (N= 74)

160Technical – Scientific Articles Natureza & Conservação - vol. 6 - n.2 - October 2008 - pp. 157-170

Clóvis Souza Bujes - Laura Verrastro

holes, and puddles in the FK and IF sites.

The Hydromedusa tectifera specimens werecaptured in the IP, FK, and IF sites and madeup 5% of total captures. They were not col-lected in sack and river habitats. They werefound in environments of low-flow waters of,in their majority, temporary nature, except fora specimen which was captured in thePintada Island/Mauá channel.

Phrynops hilarii (Figure 3.3D) was the secondmost abundant species. It was found in the IP,FK and IF areas, contributing with 21% of thecaptures. This species was present in all of thesampled habitats, occupying environmentsusually occupied by the T. dorbigni species.

The habitats preferentially occupied by chelo-nians were rivers, sacks and channels (of per-manent nature), rice irrigation channels, pud-dles and water holes (of provisory nature).Representative images of these habitats arepresented in FIGURE 4.

The more perceptible threats to the fauna andflora of the DJSP, including the chelonians, andsome measures that might help minimize nega-tive impacts are presented and discussed inTABLE 2. In a general way it was observed that,in the majority of cases, measures such as aware-

ness/education, vigilance, and legal liabilitywould minimize or even solve such problems.

DISCUSSION

Testudines represent the largest biomass infresh-water ecosystems (Bury, 1979; Souza &Abe, 1997, 2000) and their distribution andcommunity composition in fluvial environ-ments are affected both by biotic and abioticcomponents, often directly linked to ciliaryvegetation (Acuña-Mesen et al.,1983), co-spe-cific competition, predation, and temperature(Moll & Moll, 2004).

There is little in situ biological information(Richard, 1999) about the majority of SouthAmerican fresh-water turtle species. In Brazil,according to the SBH (2007), there are 36Testudine species distributed into eight fami-lies. In the state of Rio Grande do Sul, there areeleven species from four families: five marinespecies (two families) and six species from lim-netic environments (two families) (Lema,1994). Thus, the number of species listed in thisstudy, for DJSP, represents over 65% of thefresh-water chelonian fauna in Rio Grande doSul. Reptile inventory in the DJSP area (a not-published technical report done as part of theConsolidation of the DJSP subproject) hadrecorded just two Testudines species: Trachemys

Table 1: Distribution and number of specimens captured in permanent1 and temporary or ephemeral2 aquatic environments,categorized for the Delta do Jacuí State Park – RS, Brazil.

Environments/Species T. dorbigni A. spixii H. tectifera P. hilarii1Marshes 52 6 5 261Channels 53 0 1 101Sacks 0 0 0 01Rivers 5 0 0 12Irrigation channels 12 2 1 32Rice paddies 2 1 1 12Puddles 12 5 2 22Water holes 1 2 1 1

Total N 137 16 11 44

Threats

� Fires such as the ones that occurred in 2004 in theMarinheiros and Flores islands affected all the nestingsites of the chelonians. At the time, it was suspected thatthe population itself created fire spots in open areas andmarshes during the dry season, thus obtaining larger pas-ture areas, through the removal (“cleaning”) of the esta-blished vegetation, which was not grazed by cattle, in ex-change of new vegetation, that was more nutritious fordomestic animals.

� Extensive agriculture and resulting habitat fragmentation.

� Intensive agriculture: abusive extraction of water and ir-regular use of biocides and fertilizers.

� Marsh areas are filled in order to increase the area forhousing and cattle raising, an instance observed in theFazenda Kramm, where flooding fields and marshes werefilled with rice peels.

� Drainage of flooded areas or even prolonged drought pe-riods, which besides reducing activity can cause death ofindividuals and the drying of the eggs in the nests.

� Building of docks and verticality of banks through thebuilding of water contention walls that prevent the pas-sage of animals with semi-aquatic habits

161Technical – Scientific Articles Natureza & Conservação - vol. 6 - n.2 - October 2008 - pp. 157-170

Chelonians from the Delta of Jacuí River, RS, Brazil: habitats use and conservation

Engl

ish

Figure 4: Habitats used by the chelonians at Delta do Jacuí State Park, RS – Brazil. Permanent habitats: river (a), sack (b), andchannel (c); and temporary or ephemeral habitats: irrigation channel (d), puddle (e) and water hole (f).

A

D

B

E

C

F

Table 2: Main observed threats to chelonians in the Delta do Jacuí State Park, RS – Brazil, and some recommendations or mi-tigating measures to minimize the impacts.

Recommendations or mitigating measures

� Public awareness and education about damagingchanges in the environment; improvements in vigi-lance both inside the Park and in its surrounding area,and investigation of the people responsible for envi-ronmental damages and strict application of legalmeasures.

� Creation of areas of special interest to the fauna andflora, even inside the park where they were untouched,intensifying the inspection of these areas.

� To intensify inspections and enforce Brazilian legisla-tion.

� To intensify inspections and enforce Brazilian legisla-tion.

� Inform people about the correct use of the land; pub-lic awareness about damaging changes to the envi-ronment

� Constructions that are adequate or adapted to floodedareas, which allow animals to access the water andland environment (access to nests and specimen dis-persion)

Continues

162Technical – Scientific Articles Natureza & Conservação - vol. 6 - n.2 - October 2008 - pp. 157-170

Clóvis Souza Bujes - Laura Verrastro

Threats

� Eutrofization because of intensive cattle raising or by or-ganic residue discharge.

� Elimination of ciliary woods.

� Animals such as dogs that prowl nesting areas, excava-ting the nests and eating eggs and hatchlings, a fact thatis also observed in Pakistan (Akbar et al., 2006), wheredogs captured adult turtles in shallow waters

� Introduction of alien species in the Park’s area (e.g., thegolden mussel Limnoperna fortunei – Manssur et al.,2003).

� Collection of specimens, specially hatchlings, for com-merce or raise as pets and/or to keep in terrariums.

� Specimens being run over on roads, especially duringbreeding period (males migrating in search of females,adult females seeking nesting sites), movement of indi-viduals between flooded areas and dispersion of youngindividuals.

� Often breeding females were mistreated by humans whowould beat or stone them.

� Use of specimens as food, which occurs especially withthe T. dorbigni e P. hilarii species. The collection of turtlesfor human consumption in the Delta region is sporadicand opportunistic. Some female P. hilarii are caught whenthey are nesting, in this instance, both meat and eggs areconsumed.

� Commerce of hatchlings, especially the Orbigny’s slider.

Recommendations or mitigating measures

� Rigorous control of water quality and the correct treat-ment of residues.

� Environmental impact studies; regeneration of nativeriparian forests.

� Keeping domestic animals locked, and not loose inmarsh and/or nesting areas.

� Monitor and control populations of theses species:evaluation of inter-specific competition; public aware-ness; species eradication campaigns.

� Public awareness and guidance; law enforcement.

� Placement of speed bumps on the roads; building ofsubterranean bypasses in the areas where there is agreater incidence of run over of individuals.

� To inform and make people aware on how to live alonganimals who do not harm human beings.

� Monitoring studies about the consumption of wild fau-na by the human population; monitor population onthe medium and long terms; public awareness aboutthe importance of the preservation of species.

� Guidance and public awareness, enforcement of thelaw.

Continuation Table 2

dorbigni and Phrynops hilarii.

All turtles in Rio Grande do Sul are aquaticand their geographic distribution is generallylimited to the presence of water in permanentor seasonal environments. Fluvial environ-ments are dynamic and diversified ecosys-tems, made up of a variety of habitats, in-cluding main channels, tributaries, floodingplains, and lakes. According to Moll & Moll(2004), each habitat might contain a certaincommunity of chelonians. Even if the speciesmay appear anywhere in the fluvial ecosys-tem, many of them specialize in one or more

habitats where they occur in higher numbersand biomass. Thus, several habitats in a flu-vial system can present similar species com-position, but the abundance status of eachspecies will differ.

Moll & Moll (2004) verified that in 14 of 19Neotropical turtle communities, the two mostabundant species make up over 75% of thenumber of captured specimens. Among thefour species, T. dorbigni was the most abun-dant (66% of the captures), followed by P.hilarii (21% of the captures), thus corrobora-ting the authors’ assertion. Both T. dorbigni

163Technical – Scientific Articles Natureza & Conservação - vol. 6 - n.2 - October 2008 - pp. 157-170

Chelonians from the Delta of Jacuí River, RS, Brazil: habitats use and conservation

and P. hilarii behave as eurioic species, withday-time habits, easily observed during thehottest times of the day, and who regulatethermally over surfaced materials (trunks,floating vegetation, rocks, debris, and soforth). Medem (1960), Monteiro & Diefenbach(1987), Molina (1989), and Souza (1999) madesimilar comments when they studied speciessuch as the P. hilarii and P. geoffroanus.

Moll & Moll (2004) proposed that, apparen-tly, coexistence of two species from differentfamilies in the same habitat is possible be-cause there are species of fluvial turtles thatare specialist or optional. The Emydidae(considered optional fluvial turtles by Moll &Legler, 1971; Moll & Moll, 1990) have becomedominant in several rivers in regions rangingfrom Northern Mexico to Northern SouthAmerica, with the exception of small areas inCentral America, there is no specialist fluvialturtle competing for this habitat. One cannotclassify T. dorbigni and P. hilarii in this cate-gory of specialist or optional fluvial turtlesbecause, despite the apparent domination byT. dorbigni, both were species found in allsampling points (TABLE 1) and who occu-pied the most diversified habitats, both per-manent and ephemeral.

In consonance with data obtained by Richard(1999), P. hilarii was found occupying envi-ronments permanently flooded and, whenpresent in those which presented a temporarycharacter, they always were related to perma-nent habitats located nearby.

Hydromedusa tectifera (Chelidae) has presen-ted a great behavioral plasticity and resist-ance to different environmental conditions:specimens were found in sewers in the urbanarea (Pintada Island), in environments that re-ceive pesticide discharges (Fazenda Kramm),and in apparently more preserved sites (inter-nal marsh at the Flores Island). Ribas &Monteiro Filho (2002) found H. tectifera, aswell as P. geoffroanus and P. williamsi Rhodin& Mittermeier 1983 in environments withhigh degree of anthropic influence, where ri-ver pollution modifies the aquatic environ-

Engl

ish

ment through greater discharges of organicmaterial. According to Moll (1980), someTestudines species can be physiologically op-portunist, benefiting from special adaptationsto aquatic environment that present low oxy-gen levels. Besides, organic residues consti-tute an extra source of food, since the larvaeof several species of insects that inhabit theselittle oxygenized environments are the mainprey of these animals, often leading the indi-viduals of these populations to be bigger(Moll, 1980; Souza & Abe, 2001). The environ-ments occupied by H. tectifera in the DJSP aresimilar to those described by Lema & Ferreira(1990), who state that the species occur inlentic waters and in marshes, despite of beingfound by Ribas & Monteiro-Filho (2002) inlotic waters (creeks and brooks).

In the DJSP, the Chelidae Acanthochelys spixiiwas recorded in marsh environments andephemeral aquatic environments, such as irri-gation channel, rice paddies, water holes, anddraining ditches on rice plantations. D’Amato& Morato (1991) reported that this species isvery common in small creeks and marshesnear residential and industrial areas. Ribas &Monteiro-Filho (2002) reported that, in thestate of Paraná, the A. spixii was found inflooded areas which present abundance ofgrass and areas of temporary flooding duringthe raining season.

The species with the lowest capture frequen-cy was H. tectifera, however, it occurred in thethree sampled areas, while A. spixii presenteda slight higher capture frequency, but nonewas captured in one of the areas. Stone et al.(2005), when studying a turtle assembly inthe United States, argued that part of the dis-tribution or low capture frequency ofKinosternon flavescens might be due to sam-pling error, since that species spends a greatpart of the time summering or hibernating onland. H. tectifera uses to bury in the mud asthe places become dry, a behavior that was al-so observed during the winter, and reappear-ing in springtime (Lema & Ferreira, 1990).This habit was also verified by Bujes (2006,personal correspondence) for the A. spixii

164Technical – Scientific Articles Natureza & Conservação - vol. 6 - n.2 - October 2008 - pp. 157-170

Clóvis Souza Bujes - Laura Verrastro

species and might have contributed for thelow frequency estimates of occurrence andabundance relative to both species.