Biogegrafia das Asclepiadoideae (Apocynaceae) na Cadeia do ... · E ao meu pai também pelo apoio!...

Transcript of Biogegrafia das Asclepiadoideae (Apocynaceae) na Cadeia do ... · E ao meu pai também pelo apoio!...

CÁSSIA CRISTIANE DA CONCEIÇÃO BITENCOURT

Biogegrafia das Asclepiadoideae (Apocynaceae)

na Cadeia do Espinhaço: o futuro incerto dos

refúgios glaciais de Campos Rupestres

FEIRA DE SANTANA-BA

2013

Aquarela: Campos Rupestres por Pétala Gomes Ribeiro 2013

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DE FEIRA DE SANTANA

DEPARTAMENTO DE CIÊNCIAS BIOLÓGICAS

PROGRAMA DE PÓS GRADUAÇÃO EM BOTÂNICA

Biogegrafia das Asclepiadoideae (Apocynaceae) na

Cadeia do Espinhaço: o futuro incerto dos refúgios

glaciais de Campos Rupestres

CÁSSIA CRISTIANE DA CONCEIÇÃO BITENCOURT

ORIENTADOR: PROF. DR. ALESSANDRO RAPINI

Feira de Santana-BA

2013

Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-

Graduação em Botânica da Universidade Estadual

de Feira de Santana como parte do requisitos para

obtenção do título de Mestre em Botânica.

BANCA EXAMINADORA

Profª. Drª. Ingrid Koch, UFSCAR

Prof. Dr. Roy Funch, UEFS

Prof. Dr. Alessandro Rapini, UEFS

Orientador e Presidente da Banca

Feira de Santana-BA

2013

“É melhor ser alegre que ser triste

Alegria é a melhor coisa que existe

É assim como a luz no coração”

Vinicius de Moraes

1

SUMÁRIO

AGRADECIMENTOS....................................................................................................1

INTRODUÇÃO....................................................................................................... ........4

CAPÍTULO I: Centres of Endemism in the Espinhaço Range: identifying cradles

and museums of Asclepiadoideae (Apocynaceae)……………........8

CAPÍTULO II: A Cadeia do Espinhaço seria um refúgio interglacial para a flora

endêmica dos campos rupestres? Evidências da modelagem de

distribuição potencial pretérita........................................................31

CAPÍTULO III: The destiny of Campos Rupestres under climate change..............44

CONSIDERAÇÕES FINAIS.......................................................................................62

2

AGRADECIMENTOS

Primeiramente, agradeço ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Botânica (PPG-

BOT) da UEFS, principalmente aos coordenadores pelo apoio financeiro nos momentos

solicitados. E, claro, a Adriana pelos eternos esclarecimentos!

Ao AuxPe (PNADB-Capes) pela bolsa de mestrado concedida e ao REFLORA.

Os auxílios fornecidos foram de extrema importância para as viagens de campo para a

Chapada Diamantina (Bahia), Minas Gerais e Goiás.

Ao meu orientador Alessandro Rapini (Rapis!) pelos três anos de orientação

desde o trabalho no PPBio. Por todo apoio, incentivo, conhecimento e paciência que,

com certeza, foram essenciais na minha formação científica. Obrigada pelos momentos

compartilhados ao longo desses anos!

Quero agradecer também aos professores do PPG-BOT, em especial ao Luciano

pelas aulas maravilhosas (as melhores que já assisti!); ao Cássio pelas excelentes aulas

de Bioestatística e pela enorme paciência de me explicar cada dúvida sobre as análises

nesse trabalho. Também agradeço à Ana Giulietti pelas aulas ministradas com tanto

carinho, por compartilhar tanto amor à botânica e tanto conhecimento.

Ao Abel pela disponibilidade em me orientar no estágio e docência. E à

professora Lígia Funch pelas orientações nos seminários e convivência no Lab. Flora.

Ao Flávio e Efigênia que me receberam no Taxon (Lab. Taxonomia Vegetal)

desde quando cheguei à UEFS, por me ensinarem sobre a Caatinga e sobre o mundo

vegetal com tanta sabedoria!

À Tânia, pelo auxílio prestado quando precisei do REFLORA e pela bolsa de

apoio para continuar meu projeto.

Agradeço também ao Paulo de Marco Junior, pelo apoio, suporte nas análises de

modelagem, por me receber de braços abertos na UFG e por aquela frase: “Flor,

caaalma”!

Agora eu só devo agradecer ao meu tudo, aqueles dois que são o meu chão:

minha avó Onira e meu avô Silvio! Obrigada por tudo, por tanto amor, carinho,

compreensão e ensinamentos! Viver longe de vocês é, de fato, a parte mais difícil de

tudo isso! Ao meu irmão Diego pela lealdade, amizade e confiança. Aos meus amados

tios Silvana e Sid, pelo apoio durante toda a vida, pelos puxões de orelha e por tanto

amor. À minha tia devo também, a vontade de ser bióloga, pois desde pequena me

levava para o laboratório do Padre Hausser na Uni. Ao meu primo amado Teteu pelo

3

carinho. À minha mãe e ao Mário pelo apoio! Ao meu irmãozinho Xande por amar tanto

a “maninha” dele. E ao meu pai também pelo apoio!

Ao meu amor Leo, por estar sempre comigo! Por tantos ensinamentos sobre os

mais variados assuntos! Por me ensinar a levar a vida com mais calma e menos

preocupações, por querer sempre me ver feliz e alegre. À Ledinha por ter sido uma mãe

em tantos momentos difíceis, por me escutar, dar conselhos e querer sempre o meu

bem! Obrigada por todo apoio meus amores!

Aos meus amigos amados Lau e Dinho por estarem sempre perto e me apoiando!

Às minhas bests gaúcha que mesmo distante eu não esqueço e quero sempre por

perto: Dani Machado, Gabi Lanzoni e Kenita Litter.

À Salete por ter me orientado durante toda iniciação científica, apresentado à

botânica e me ensinado tanta coisa. Também a todo pessoal do Anchietano por tanto

tempo de convivência e amizade: Ivone, Denize, Padre Inácio e amigos que por lá

passaram: Fabi, Virgínia, Vini, Veri, André e Julian.

A todo pessoal do Taxon pela convivência, amizade e resenhas: Leilton, Rey,

Carla, Karena, Lucas, André, Evandro, Herlon e Mari Mota.

À minha amiga Lara, pelo apoio nos momentos mais difíceis em que eu mais

precisei. Por ser a amiga que eu tanto queria por aqui. Obrigada pelos maravilhosos

conselhos e companheirismo. Valeu Puglinhaaaaa...rsrsrs! Agradeço também à tia

Marcinha, ao tio Sérgio e ao Serginho por me receberem tão bem na casa de todos

vocês. Obrigada por tudo!

À minha doidinha mais amada Pél, obrigada por tanto carinho comigo desde

quando estudamos juntas para a seleção. Obrigada por me ouvir e por sempre me apoiar

nos momentos em que foi necessário. E ainda por ser essa amiga linda, alegre e cheia de

luz que ilumina minha vidinha! Agradeço também à tia Dinalva pelo carinho, atenção,

orações e preocupações.

Agradeço também à Isys por tudo, durante todo o mestrado! Pela convivência,

amizade, carinho e dedicação. Serei eternamente grata! À vó Laura, ao vô Olegário por

tanto amor, por me receberem maravilhosamente bem em sua residência, também à tia

Cris por tanta atenção e gentileza! Obrigada por tudo!

Ao Leilton por todo o auxilio com o geoprocessamento de dados. Obrigada por

ter me ajudado do início até a última hora. Você foi fundamental na execução do

trabalho. Serei eternamente grata! Também pela parceria nas viagens a São Paulo e

Fortaleza. Enfim, por todos os anos de convivência!

4

À Kamis (peque Lopes) pelo apoio e amizade!

Aqueles que me receberam desde o início e me apoiaram: Marla, Aline, Ana

Luiza, Ricardo e Anderson. Obrigada!

À Ju Rando e o Bejô pela cia e amizade durante toda a estadia em Feira!

A todos os amigos do PPG-BOT e da UEFS: Gabi Barros, Eveline, Danilo, Earl,

Karol Coutinho, Marlon, Ariane, Christian, Cris Snack, Maria Cristina, Domingos,

Fábio, Pati Luz, Sâmia, Richard, Aline Quaresma (Minerinha querida!), Ayumi (Japa!),

Gabi Almeida, Marcelo, Luiz, Hibert, Mateus e Cleiton.

À Zezé, Teo e Silvinha do HUEFS.

Aos amigos da UFG e por todo apoio: principalmente Daniel, Carol Nóbrega,

Camis, Pedro e Andressa. E a todo pessoal do Lab. MetaLand pelo tempo de

convivência. À Tailise, Paola e Clara pelo abrigo durante todo o tempo em que estive

em Goiânia.

Aos funcionários do LABIO por tantos bons dias e resenhas: Dona Nem, Juci,

Jacson e aos vigias da noite também!

Por fim, agradeço a todos que de alguma forma participaram de tudo isso!

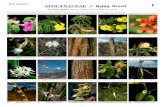

Minaria harleyi, endêmica da Chapada Diamantina

INTRODUÇÃO

5

INTRODUÇÃO

A distribuição de organismos está relacionada a diferentes padrões de variação em

escalas macroespaciais e regionais. A Biogeografia é a ciência que busca, então, detectar e

explicar esses padrões. Através dessa disciplina podemos tentar entender como as espécies ou

linhagens estão atualmente distribuídas; qual o papel da topografia e do clima nessa

distribuição; como eventos históricos, como o soerguimento dos Andes ou as flutuações

climáticas do Pleistoceno, podem ter influenciado essa distribuição; como populações

isoladas divergiram, levando à diversificação das linhagens; e ainda, por que a biodiversidade

está distribuída desigualmente. Novas técnicas e programas computacionais mais sofisticados

têm facilitado o avanço das pesquisas em biogeografia e os estudos se tornaram mais

objetivos nas últimas décadas. Além disso, as mudanças climáticas têm exigido que

pesquisadores procurem prever distribuições futuras como estratégia para a conservação da

biodiversidade. A biogeografia é, portanto, uma disciplina que aplica teoria a dados

empíricos a partir da comunhão entre diversas abordagens da ecologia, sistemática, genética

de populações, evolução e geologia (Brown e Lomilino, 2006).

A região neotropical abriga a maior biodiversidade do planeta e aproximadamente um

terço das espécies de angiospermas estão concentradas ali. Vários pesquisadores vêm

buscando, então, explicações para tamanha riqueza. Em regiões montanhosas, a diversidade

de espécies costuma ser ainda maior e os índices de endemismos superam aqueles

encontrados nas áreas mais baixas que as circundam. A Cadeia do Espinhaço, no leste do

Brasil, encontra-se em uma zona de transição por conta de diferentes esferas (Figura 1): (1)

trata-se de um divisor entre as bacias do São Francisco e do Atlântico Leste, além de estar no

entremeio de diversas sub-bacias; e (2) é intersectada por três domínios fitogeográficos: a

Caatinga ao norte, a Mata Atlântica a sudeste e o Cerrado a sudoeste. Nos topos de morros,

ela abriga uma vegetação aberta associada a solos quártzicos denominada campos rupestres.

Essas áreas são caracterizadas pela alta diversidade de espécies, em grande parte

microendêmicas (Harley, 1988; Giulietti et al., 1997; Rapini et al., 2008).

A Cadeia do Espinhaço é um dos principais centros de diversidade das

Asclepiadoideae (Rapini, 2010). A subfamília abrange principalmente plantas perenes; são

arbustos ou subarbustos eretos, volúveis ou prostrados, latescentes. Elas chamam a atenção

especialmente pela morfologia floral diferenciada, uma das mais complexas dentre as

INTRODUÇÃO

6

Figura 1. Representação da Cadeia do Espinhaço intersectada por três domínios

fitogeográficos (ver legenda); e entremeada pela sub-bacias do São Francisco no oeste e

Atlântico Leste no leste do Brasil.

INTRODUÇÃO

7

angiospermas, apresentando gineceu e androceu fundidos em um ginostégio e os grãos de

pólen arranjados em polínios. Antes considerada no nível de família (Asclepiadaceae),

encontra-se atualmente posicionada dentre as Apocynaceae (e.g. APG III, 2009). As

Asclepiadoideae têm sido estudadas na Cadeia do Espinhaço de maneira mais contínua e

intensiva desde a década de 1990, sendo um dos poucos grupos de plantas cujas espécies são

suficientemente conhecidas e podem ser utilizadas como modelos em estudos biogeográficos,

evolutivos e de conservação na região (Rapini, 2010).

Neste estudo, nós utilizamos as Asclepiadoideae como base para entender os padrões

de distribuição atual nos campos rupestres da Cadeia do Espinhaço e projetar essa

distribuição para o passado e para o futuro. De modo geral, nossos objetivos foram: (1)

detectar os centros de endemismos ao longo da Cadeia do Espinhaço e entender as relações

florísticas dos campos rupestres com as floras no seu entorno; (2) verificar se os centros de

endemismos atuais correspondem a refúgios históricos dos campos rupestres durante períodos

interglaciais; (3) predizer áreas futuras de campos rupestres e a eficácia das unidades de

conservação frente ao aquecimento global. No capítulo 1, nós empregamos análises de

similaridade florística e parcimônia de endemismo, associando-as com índices de

endemismos, buscando padrões atuais de distribuição nos campos rupestres. A distribuição

histórica dos campos rupestres é investigada no Capítulo 2 através da modelagem de espécies

de Asclepiadoideae endêmicas da Cadeia do Espinhaço para a Última Máxima Glacial, o

Holoceno Médio e o período pré-industrial. Com base no mesmo conjunto de espécies

endêmicas, nós simulamos, também, a distribuição dos campos rupestres para o futuro (2020,

2050 e 2080) e estimamos as taxas de extinção para os campos rupestres para as próximas

décadas.

Referências

APG III (2009) An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders

and families of flowering plants: APG III. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society

161, 105–121.

Brown, J. & Lomolino, M. (2006) Biogeografia 3a ed– Sinauer, Sunderland.

Giulietti, A.M., Pirani, J.R. & Harley, R.M. (1997) Espinhaço Range Region, Eastern Brazil.

In Centres of plant diversity. A guide and strategy for their conservation. v.3. The

Americas (S.D. Davis, V.H. Heywood, O. Herrera-Macbryde, J. Villa-Lobos & A.C.

Hamilton, eds.). IUCN Publication Unity, Cambridge, 397–404.

INTRODUÇÃO

8

Harley R.M. (1988) Evolution and distribution of Eriope (Labiatae), and its relatives, in

Brazil (P.E. Vanzolini & W.R. Heyer, eds.). Proceedings of a Workshop on

Neotropical Distribution Patterns. Academia Brasileira de Ciências, Rio de Janeiro,

71–120.

Rapini, A., Ribeiro, P.L., Lambert, S. & Pirani, J.R. (2008) A flora dos campos rupestres da

Cadeia do Espinhaço. Megadiversidade 4, 15–23.

Rapini, A. (2010) Revisitando as Asclepiadoideae (Apocynaceae) da Cadeia do Espinhaço.

Boletim de Botânica da Universidade de São Paulo 28, 97-123.

9

CAPÍTULO I

Centres of Endemism in the Espinhaço Range:

identifying cradles and museums of Asclepiadoideae

(Apocynaceae)

Submetido para Sistematics and Biodiversity

CAPÍTULO I – Centres of Endemism in the Espinhaço Range

10

Although the high diversity of neotropical plants is often associated with rain forests,

another important location is open vegetation at mountain tops. In the present study, we

investigated the phytogeographic patterns of the Espinhaço Range, in eastern Brazil, a

region characterised by campos rupestres and marked by high levels of plant richness

and endemism. Based on the occurrence of Asclepiadoideae (Apocynaceae) in a grid of

0.5º x 0.5º cells, we conducted cluster analyses and parsimony analysis of endemicity

(PAE). We also calculated indexes of diversity and endemism and examined the

distribution of palaeo- and neo-endemics. According to our data, the topographic gap

between the Espinhaço Range of Minas Gerais and Bahia seems to be an important

constraint for the dispersion of endemics, and the floristic similarity between northern

Minas Gerais and Bahia is caused by species with broad distribution. Based on the

seven areas of endemism that emerged from PAE, we defined five principal centres of

endemism in the Espinhaço Range, including the region comprising Serra do Cipó and

the Diamantina Plateau, in Minas Gerais, as the major Asclepiadoideae cradle, and

Chapada Diamantina, in Bahia, as an Asclepiadoideae museum.

Key words: Biogeography, Brazil, campos rupestres, conservation, endemics,

Neotropics.

CAPÍTULO I – Centres of Endemism in the Espinhaço Range

11

“The campo rupestre flora, highly adapted to these very specialised

conditions, displays a floristic richness and degree of endemism hard

to equal elsewhere in the New World.” (Harley, 1988)

Introduction

The Neotropics shelters almost 40% of all species of seed plants (Antonelli &

Sanmartín, 2011). Brazil contains approximately one third of these species, and more

than half of them are endemic (Forzza et al., 2012). This diversity is often associated

with exuberant tropical rain forests, but an important part of the diversity is restricted to

open vegetation at the top of mountain ranges.

The Espinhaço Range in eastern Brazil is characterised by rock field vegetation

known as campos rupestres, which mainly appear above 900 m. The region represents

approximately 1% of Brazilian territory but houses approximately 10% of the plant

diversity reported for the entire country (Rapini, 2010). Despite being surrounded by

Atlantic rain forests in the southeast, Cerrado savannas in the southwest and the

seasonally dry Caatinga forests in the north, the campos rupestres of the Espinhaço

Range (Fig. 1) maintain their individuality and present one of the highest levels of plant

endemism in Brazil (for a characterisation of the campos rupestres, please see Giulietti

& Pirani, 1988; Harley, 1988, 1995; Giulietti et al., 1997; Rapini et al., 2008).

The Espinhaço Range is located between the São Francisco and the Atlantic

basins and is traditionally divided in two portions, one in Minas Gerais State and the

other in Bahia State (Fig. 1). The topographic discontinuity between them is paralleled

by their different flora, and few endemic species are shared by both portions (Harley,

1988, 1995; Rapini et al., 2002, 2008). Phytogeographic studies have been concentrated

in the southern portion in Minas Gerais. Rapini et al. (2002), for instance, divided this

portion into four sectors based on the topography and floristic composition of asclepiads

(Apocynaceae). More recently, Echternacht et al. (2011) defined 10 areas of endemism

based on the co-occurrence of 178 endemic species and identified six biogeographic

areas.

Both Rapini et al. (2002) and Echternacht et al. (2011) highlighted the uneven

collection effort along the Espinhaço Range and the direct correlation between sampling

and richness. As shown with asclepiads (Rapini et al., 2002), there seems to be an

evident decrease in floristic collections northward along the Espinhaço Range of Minas

CAPÍTULO I – Centres of Endemism in the Espinhaço Range

12

Figure 1. Espinhaço Range (above 900 m) showing its position among the Atlantic

forest (AF), Caatinga (CA) and Cerrado (CE) domains and sub-basins (SF denotes the

São Francisco basin; the others sub-basins belong to the East Atlantic basin). The

southern Minas Gerais (S), Serra do Cipó (C), Diamantina Plateau (D) and northern

CAPÍTULO I – Centres of Endemism in the Espinhaço Range

13

Minas Gerais (N) in the state of Minas Gerais (MG) and the Chapada Diamantina (CH)

in Bahia (BA) are indicated.

Gerais, which continues to the Bahia portion. The last decade was marked by important

floristic advances, and the imbalance between the two portions has decreased; however,

the overall sampling effort in Bahia is still approximately half of that in Minas Gerais

and remains concentrated in particular areas of Chapada Diamantina (Rapini, 2010).

Although floristic knowledge of the Espinhaço is still incomplete and uneven,

some biogeographic patterns have emerged. The region is marked by two principal

centres of endemism, one in the Minas Gerais portion, comprising Serra do Cipó and

the Diamantina Plateau (Rapini et al., 2002; Echternacht et al., 2011), and a secondary

centre in Chapada Diamantina, in the Bahia portion (Rapini, 2010). The number of

species endemic to Bahia is usually lower than that in the centre of the Espinhaço Range

of Minas Gerais, but they are morphologically disparate, which is often represented

taxonomically by monospecific genera from this portion (Rapini et al., 2008).

Apparently, lineages isolated in the northern region evolved without producing a great

number of species when compared with lineages in the southern portion, either because

of lower diversification rates or because of higher extinct rates (Rapini, 2010). Minaria

(Apocynaceae), a genus with 21 species, presents the same pattern, with 13 species

endemic to the Espinhaço of Minas Gerais (Konno et al., 2006) and two

morphologically disparate species endemic to the Espinhaço of Bahia (Silva et al.,

2012). Despite the differences in the number of species and endemics, both regions

present areas with high phylogenetic diversity and endemism for Minaria (Ribeiro et

al., 2012). Therefore, lineages in the Espinhaço of Bahia and Minas Gerais seem to have

been subjected to different histories, and the two regions are important areas for

phylogenetic conservation, which cannot always be directly inferred by the number of

species or endemics alone.

The high diversity of plants in the Espinhaço Range may be caused by different

individual factors or, more likely, by a combination of them (Giulietti & Pirani, 1988;

Harley, 1988, 1995; Giulietti et al., 1997; Rapini et al., 2008). The 1000 km latitudinal

range completely nested in a tropical region, the high altitudinal range provided by the

mountainous topography and the connectivity among three discrepant and rich

phytogeographic domains provide conditions for the establishment of plant lineages

with different requirements. Furthermore, the topography and soil heterogeneities

(Conceição et al., 2005; Bennites et al., 2007) are responsible for disjunctions at

CAPÍTULO I – Centres of Endemism in the Espinhaço Range

14

different scales and create microhabitats that favour in situ diversification, which seems

to have greatly contributed to the overall plant diversity in the Espinhaço Range.

The diversification of plants in the Espinhaço Range is usually associated with

Pleistocene climatic fluctuations (e.g. Rapini et al., 2008). However, there are few

phylogenetic studies that include species endemic to the region, and most theories on

the plant diversification in the Espinhaço Range remain speculative (Fiaschi & Pirani,

2009). Calibrated phylogenies of plant groups predominantly endemic to the Espinhaço

Range is available for only two genera thus far, and they have provided contrasting

outcomes. Hoffmannseggella H.G. Jones (Orchidaceae) is postulated to have radiated

mainly after hybridisations caused by expansions during the Miocene (Antonelli et al.,

2010), while Minaria (Apocynaceae) seems to have radiated after gradual range

fragmentations in the Pleistocene (Ribeiro 2011; Ribeiro et al., 2012, in review).

Likewise, few studies have investigated the floristic relationships of campos

rupestres, all them based on local floristic inventories of megadiverse families such as

Orchidaceae (Azevedo & van den Berg, 2007; Abreu et al., 2012), Leguminosae (Dutra

et al., 2008), Poaceae (Garcia et al., 2009; Longhi-Wagner et al., 2012) and Asteraceae

(Borges et al., 2010). Typically, these studies show low similarity (< 50%) among sites,

a pattern already expected because sites in the Espinhaço Range, even when close to

each other, share relatively few species (e.g. Zappi et al., 2003). Interestingly, in most

of these studies, Grão-Mogol, in the northern Espinhaço Range of Minas Gerais, was

shown to be more similar to sites in Chapada Diamantina, in the Bahia portion, than to

sites in Minas Gerais, contrasting with the postulated floristic dichotomy between the

two portions of the Espinhaço Range.

In this study, we analyse the floristic relationships between the Espinhaço Range

and its surroundings as well as within the Espinhaço Range. With this approach, we

intended to 1) detect patterns that may suggest the floristic influence of adjacent

vegetation on the flora of campos rupestres and 2) evaluate the floristic discontinuity

between the two portions of the Espinhaço Range. Our main objectives, however, are to

1) identify centres of endemism through the entire Espinhaço Range without using

predefined areas and 2) classify the identified areas into plant museums and cradles.

Material and Methods

Few plant groups have been studied throughout the whole Espinhaço Range and

have had a representative amount of species endemic to this region sampled in

CAPÍTULO I – Centres of Endemism in the Espinhaço Range

15

phylogenetic studies. Asclepiadoideae (Apocynaceae) is one of the few. This subfamily

is diversified in these mountains, where it is represented by 133 species, approximately

30% of which are endemic. The group has been studied in the Espinhaço Range for

more than a decade, and several species from this region were sampled in phylogenetic

studies with molecular data. Together, these studies have provided support for

continuous taxonomic rearrangements, and the classification of approximately 20% of

Asclepiadoideae species from the Espinhaço Range has been changed in less than 10

years of such research (Rapini, 2010).

The present study is based on a database of the Brazilian Asclepiadoideae,

comprising records of more than 18,000 specimens deposited at the principal herbaria of

Brazil, Europe and the United States. GPS coordinates were confirmed or obtained with

the help of Google Earth, and a matrix of the geographic distribution was built. Records

along the Espinhaço Range (above 900 m) and its surroundings (50 km away from it)

were mapped on a grid of 0.5º x 0.5º cells (ca. 50 x 50 km) to build a presence-absence

matrix (available upon request from CB). The number of collections, species and

endemics as well as the Gini-Simpson diversity were calculated and mapped using

Biodiverse version 0.17 (Laffan et al., 2010). Correlation analyses between sampling

(number of collections) and number of species, number of endemics and diversity were

performed in SAM (Spatial Analysis in Macroecology 3.1; Rangel et al., 2010).

A UPGMA cluster analysis based on the Sorensen-Dice similarity coefficient

was used to compare cell compositions. This analysis was calculated with PAST version

1.89 (Hammer et al., 2009), using 5,000 replications for bootstrap support, and was also

analysed visually for mapping clusters in Biodiverse.

A parsimony analysis of endemicity (PAE) was conducted in PAUP version 4.10

(Swofford, 2000) as a heuristic search with 1,000 replications from random additions

and TBR swapping, saving no more than 15 trees per replication; trees were rooted in a

hypothetical area with absences only. For bootstrap support, the same commands were

applied, but replications were initiated using simple additions. Cells sharing more than

one exclusive species in the strict consensus tree were considered areas of endemism

(sensu Morrone, 1994). Weighted endemism (WE), an index that is inversely

proportional to the sum of species’ ranges, and the corrected weighted endemism

(CWE), which normalises WE by the number of species (Crisp et al., 2001; Laffan &

Crisp, 2003; Laffan et al., 2012) and provides the mean representation of the cell for the

species’ range, were also calculated in Biodiverse (Laffan et al., 2010).

CAPÍTULO I – Centres of Endemism in the Espinhaço Range

16

Species restricted to the Espinhaço Range were classified as palaeoendemic and

neoendemic. We used the boundary between the Pliocene and Pleistocene (2.6 million

years) as a primary criterion for this classification. This limit was established based on

the period of Minaria radiation estimated by Ribeiro (2011; Ribeiro et al., in review).

However, the taxonomy and biogeographic criteria assessed by López-Pujol et al.

(2011) were also considered. In this sense, endemics whose divergence was estimated

for the Tertiary and are sisters to well-radiated clades, present a disjunct distribution or

have a singular morphology were classified as palaeoendemics. By contrast, endemics

that diverged during the Quaternary and are the product of recent irradiations, usually

forming complexes of species that either occur together or in adjacent areas, were

considered neoendemics. We used the most recent calibrated phylogeny of

Apocynaceae (Ribeiro, 2011; Ribeiro et al., in review) as the principal reference for

species age, but additional phylogenetic studies (e.g. Liede-Schumann et al., 2005;

Rapini et al., 2007; Silva et al., 2010; Liede-Schumann & Meve, 2013) were also

considered. Species whose information was not sufficient for confident classification

were treated as uncertain.

Results

Our sampling comprised 3,871 specimens, 64% of which were from the Espinhaço

Range and 36% of which were from its surroundings. The sampling of the whole study

area, comprising both the Espinhaço Range and its surroundings, included 160 species,

133 of which occur in the Espinhaço Range and 42 of which are endemic (1,103

records). Collections were mostly concentrated in the southern portion of the Espinhaço

Range, in Minas Gerais, and, secondarily, in Chapada Diamantina, in Bahia. Likewise,

the richness of species and endemics are both concentrated in the southern range, as are

areas with higher diversities (Fig. S1). This pattern is confirmed by the high correlation

between the number of collections and species richness (r = 0.886; p = 0), the number of

endemics (r = 0.730; p = 0) and diversity (r = 0.213; p = < 0.001).

In the cluster analysis considering all species of Asclepiadoideae, a group

comprising 24 of the 36 cells with species endemic to the Espinhaço Range is formed.

This group is roughly divided into Minas Gerais and Bahia portions. However, cells in

northern Minas Gerais are more similar to those in Bahia than to the other cells in

Minas Gerais. Considering only species endemic to the Espinhaço Range, a rough

CAPÍTULO I – Centres of Endemism in the Espinhaço Range

17

Figure 2. Cluster analyses of Asclepiadoideae compositions in cells of 0.5o × 0.5

o,

using the Sorensen similarity coefficient and UPGMA. Above, a dendrogram with cells

of the Espinhaço Range and its surroundings, highlighting the largest cluster and the

dichotomy between the northern and southern subgroups. Bellow, a dendrogram of cells

with species endemic to the Espinhaço Range, roughly divided into the Bahia (BA) and

Minas Gerais MG) groups.

division between Minas Gerais and Bahia regions is also present. However, there is one

cell in Bahia that is more similar to those in Minas Gerais. In both cases, the similarity

between the two groups is very low (Fig. 2).

CAPÍTULO I – Centres of Endemism in the Espinhaço Range

18

PAE produced 9,180 trees (82 steps) based on 34 parsimony-informative

characters (species) and indicated six areas of endemism (Fig. 3), five of which are in

the Minas Gerais portion, which houses 31 exclusive species, corresponding to

approximately 75% of the endemic species. The area with the highest number of

exclusive species (7) is Serra do Cipó (A32-A33; bootstrap = 89%), in the Rio das

Velhas sub-basin, part of the São Francisco basin in western Minas Gerais. The other

three areas in Minas Gerais contain only two exclusive species each, one in the

Figure 3. Strict consensus obtained with parsimony analysis of endemicity. Terminal

areas (A) correspond to cells in Fig. 1 denoting their sub-basins; numbers on branches

refer to species (see Table 1) that are exclusive to the areas of endemism, with bootstrap

support between parentheses. OG – hypothetical outgroup.

southernmost region of the Espinhaço, between the Rio das Velhas and Rio Doce sub-

basins (A27-A35; BS = 51%), and another in the northern Espinhaço of Minas Gerais,

comprising Itacambira and Botumirim, in the Rio Jequitinhonha sub-basin (A21-A22;

CAPÍTULO I – Centres of Endemism in the Espinhaço Range

19

BS = < 50%) in the East Atlantic basin. The last two areas in this region are in the

Diamantina Plateau, one in the Rio das Velhas sub-basin (A31) and the other in

Jequitinhonha sub-basin (A23), at the intersection of the São Francisco and East

Atlantic basins. One area of endemism was detected in Chapada Diamantina (A4-A5

and A7-A8; BS = 70%), comprising part of the Jequirica-Paraguaçu and the Rio de

Contas sub-basins, in Bahia.

The centre of the Espinhaço Range in Minas Gerais, comprising Serra do Cipó

and the Diamantina Plateau, at the intersection of the Rio das Velhas, Doce and

Jequitinhonha sub-basins, presents the highest values of WE. According to the CWE,

however, areas with higher values of endemicity are more dispersed throughout the

region. CWE values are relatively lower than the WE values in the Diamantina Plateau

but higher in southern and northern regions of Minas Gerais, in Serra do Cipó, and in

the Rio de Contas sub-basin in Chapada Diamantina (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Distribution of weighted endemism (WE) and corrected weighted endemism

(CWE) on a grid of 0.5o × 0.5

o cells.

Only Monsanima morrenioides from Rio de Contas in Bahia could be

confidently classified as palaeoendemic, while 15 species were classified as

neoendemic. Of the remaining 26 endemics, three are postulated to be palaeoendemic,

CAPÍTULO I – Centres of Endemism in the Espinhaço Range

20

18 are postulated to be neoendemic, and eight could not be classified (Table 1).

Neoendemics are restricted to the Minas Gerais region, mainly at the intersection

between the Rio das Velhas and Rio Doce sub-basins but reaching the Jequitinhonha

sub-basin to the north. No species from Bahia was confidently classified as neoendemic;

they are only represented in this region by species with questionable classification.

When palaeoendemic species with questionable classification are considered, there are

more of these species in Bahia than in Minas Gerais (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Distribution of the number of neoendemics (only including species that were

confidently classified) and the potential number of palaeoendemics (including species

confidently classified and those with uncertain classification).

Discussion

High amounts of species and endemics throughout the Espinhaço Range are

significantly correlated with higher numbers of collections, as previously suggested for

Asclepiadoideae (Rapini et al., 2002; Rapini, 2010) and verified for endemic species of

17 families in the Espinhaço Range of Minas Gerais (Echternacht et al., 2011). A

similar pattern was also found for diversity, with higher diversities in areas with higher

numbers of species and collections. Sampling biases limit the utility of biological data

CAPÍTULO I – Centres of Endemism in the Espinhaço Range

21

Table 1. List of species endemic to the Espinhaço Range and the type of endemism,

estimated age, whether it was sampled in phylogenetic analyses and the source of the

biogeographic information. Mi = Miocene; Pli = Pliocene; X = with chronogram; –

lacking data; Distribution: D = disjointed; I = isolated in a small area; AG = Aggregate,

with co-occurrence of cogeneric species; R = restricted and have not yet dispersed.

Species Endemics Age Molecular Phylogenetics Biogeographic data

1 Barjonia chlorifolia Decne. ? Pli/Ple X D

2 Ditassa aequicymosa E.Fourn. N? ? - AG

3 D. auriflora Rapini N? ? - AG/R

4 D. cipoensis (Fontella) Rapini N? ? - AG/R

5 D. cordeiroana Fontella N? ? - AG/R

6 D. eximia Decne. N? ? - AG/R

7 D. fasciculata E.Fourn. N Ple X AG/R

8 D. itambensis Rapini N? ? - AG/R

9 D. laevis Mart. N? ? - AG/R

10 D. longicaulis (E.Fourn.) Rapini ? ? - AG/D

11 D. longisepala (Hua) Fontella & E.A.Schwarz N? ? - AG/R

12 D. melantha Silveira N? ? - AG

13 D. pedunculata Malme N? ? - AG/R

14 Hemipogon abietoides E.Fourn. N Ple X AG/R

15 H. furlanii (Fontella) Rapini N? ? - I

16 H. hatschbachii (Fontella & Marquete) Rapini N Ple X AG/R

17 H. hemipogonoides (Malme) Rapini N Ple X AG/R

18 H. luteus E.Fourn. N Ple X AG/R

19 H. piranii (Fontella) Rapini N? ? - AG/R

20 Matelea morilloana Fontella ? ? - I

21 Metastelma giuliettianum Fontella N? ? - AG/R

22 M. harleyi Fontella N? ? - AG/R

23 M. myrtifolium Decne. N? ? - AG/R

24 Minaria bifurcata (Rapini) T.U.P.Konno & Rapini N? ? - AG/R

25 M. campanuliflora Rapini N Ple X AG/R

26 M. diamantinensis (Fontella) T.U.P.Konno & Rapini N Ple X AG/R

27 M. ditassoides (Silveira) T.U.P.Konno & Rapini N Ple X AG/R

28 M. grazielae (Fontella & Marquete) T.U.P.Konno & Rapini N Ple X AG/R

29 M. harleyi (Fontella & Marquete) Rapini & U.C.S.Silva ? Pli/Ple X AG/R

30 M. hemipogonoides (E.Fourn.) T.U.P.Konno & Rapini N Ple X AG/R

CAPÍTULO I – Centres of Endemism in the Espinhaço Range

22

Cont. Table 1

Species Endemics Age Molecular Phylogenetics Biogeographic data

31 M. inconspícua (Rapini) Rapini ? ? - AG/R

32 M. magisteriana (Rapini) T.U.P.Konno & Rapini N Ple X AG/R

33 M. monocoronata (Rapini) T.U.P.Konno & Rapini N? ? - AG/R

34 M. parva (Silveira) T.U.P.Konno & Rapini N Ple X AG

35 M. polygaloides (Silveira) T.U.P.Konno & Rapini ? Pli X I/AG?

36 M. refractifolia (K.Schum.) T.U.P.Konno & Rapini N Ple X AG/R

37 M. semirii (Fontella) T.U.P.Konno & Rapini N Ple X AG/R

38 M. volubilis Rapini & U.C.S.Silva ? Pli/Ple X AG/R

39 Monsanima morrenioides (Goyder) Liede & Meve P Mi X R

40 Oxypetalum montanum Mart. ? ? - D

41 O. polyanthum (Hoehne) Rapini N? ? - AG/R

42 O. rusticum Rapini N? ? - AG/R

(Pyke & Ehrlich, 2010) and may distort our perception of species distribution and

occurrence along the Espinhaço Range (Rapini et al., 2002). This pattern seems to be

result of a phenomenon called the botanist effect (Moerman & Eastbrook, 2006),

according to which some areas are perceived as more diverse only because they are

closer to botanical institutions and, therefore, are more sampled. However, the

proportion of endemics seems to be less affected by sampling artefacts, and an inverse

relationship may also be considered. Knowing that people tend to settle in areas with

higher productivity, which usually shelter more species, botanists also tend to be closer

to biologically richer areas (Pautasso & McKinney, 2007). In this case, the most

sampled areas would also be the richest ones. The same logic was also applied by

Echternacht et al. (2011), who considered the possibility that researchers could be

attracted to areas sheltering more endemic species more often, which could be the cause

of the uneven sampling along the Espinhaço Range.

Few endemics occur along the entire Espinhaço Range, but areas sharing

different combinations will have a greater chance of presenting higher similarities.

Areas with more endemic species roughly formed a group that can be divided into

northern (Bahia) and southern (Minas Gerais) subgroups with low similarity; the region

between these subgroups, with few or no endemic species, was separate and contained a

mixed floristic composition.

CAPÍTULO I – Centres of Endemism in the Espinhaço Range

23

The flora in the Espinhaço Range of Bahia is more similar to the adjacent areas

to the north, showing the predominant influence of Caatinga in this portion of the

Espinhaço Range. The similarity of the northern Minas Gerais with areas of Bahia

observed in this study, a pattern also found in other groups of plants (Azevedo & van

den Berg, 2007; Dutra et al., 2008; Garcia et al., 2009; Borges et al., 2010; Abreu et al.,

2012; Longhi-Wagner et al., 2012), is evidence of the regional climatic influence of

Caatinga on the composition of northern Minas Gerais, mostly affecting species with

broader distributions. By contrast, in most part of Minas Gerais, the flora of the

Espinhaço Range is more similar to that of adjacent areas to the west, showing an

influence of the Cerrado in their compositions. This pattern contrasts with that noted by

Versieux & Wendt (2007), who surveyed more species of Bromeliaceae shared by

campos rupestres and Atlantic forest than were shared by campos rupestres and the

Cerrado.

Considering only endemic species, the dichotomy between Minas Gerais and

Bahia becomes sharper, although one cell in the Bahia portion is grouped with those of

Minas Gerais, suggesting a higher influence of the Minas Gerais endemic flora on the

Bahia portion than the inverse. Therefore, it seems that the range of endemics, which

are usually species with limited dispersion, is more constrained by the topographic gap

between the two portions of the Espinhaço Range than by their environmental

conditions. The 300-km disjunction between the campos rupestres of Minas Gerais and

Bahia represents an important barrier for most endemics, restricting their migration

between the two mountain massifs, as claimed by Harley (1988). The cladogenesis

between lineages of these two regions was one of the first events in the diversification

of Minaria, indicating that this barrier has been in effect since the Tertiary, more than 3

million years ago (Ribeiro, 2011; Ribeiro et al., in review).

Due to uneven sampling throughout the Espinhaço Range, inaccurate geographic

information for several records and the restricted area of occurrence of most endemic

species, cells of 0.5o x 0.5

o are most suitable for a broad range of analyses in the region.

Such cells allow general floristic comparisons and can also be useful in PAE, which is

directly affected by the size of spatial unities (Morrone & Escalante, 2002). The utility

of PAE for historical biogeography has been contested because it can explain only a

limited combination of historical events (Brooks & van Veller, 2003). Nevertheless, this

method may be useful in recovering and describing distribution patterns (Garzón-

Orduña et al., 2008) and is an operational tool for diagnosing areas of endemism based

CAPÍTULO I – Centres of Endemism in the Espinhaço Range

24

on arbitrary spatial units (e.g. Crother & Murray, 2011). However, PAE presents low

performance in recovering overlapping and disjointed patterns (Casagranda et al., 2012)

and grouping areas of endemism (Brooks & van Veller, 2003). Therefore, areas of

endemism that emerged from PAE are preliminary units in the process of defining

centres of endemism and can be refined based on species’ distribution.

Six areas of endemism based on the presence of more than one exclusive species

were recovered in the Espinhaço Range by PAE. They can be divided into five centres

of endemism. Chapada Diamantina is the largest one. The others are core areas of the

sectors defined by Rapini et al. (2002) for Minas Gerais: the southern and northern

Espinhaço Range, Serra do Cipó (the most important, housing seven exclusive species)

and the Diamantina Plateau (with two minor centres, one in the Rio das Velhas sub-

basin and the other in the Jequitinhonha sub-basin).

The comparisons between WE and CWE highlight the influence of richness and

species distribution per cell, showing that Serra do Cipó in the Rio das Velhas sub-basin

is the area with the highest richness of microendemics. The other areas, especially in

southern and northern Minas Gerais and in Chapada Diamantina, are important mostly

because of the limited range of some endemics. The Diamantina Plateau presents a high

number of endemics, but their distribution is usually broader than in other areas. This

may be associated with the larger continuous area of campos rupestres in this region,

allowing species restricted to the Diamantina Plateau to have larger distributions.

Although several species of Asclepiadoideae could not be confidently classified

as palaeo- and neo-endemics yet, it is possible to note that most Asclepiadoideae

species restricted to the Espinhaço Range are neoendemics. They are concentrated in the

Minas Gerais region, which is composed of four centres of endemism, all smaller than

the one in Bahia. This pattern reflects the higher fragmentation of the Minas Gerais

region and may help to explain the high number of neomicroendemics in this region,

mainly from Serra do Cipó to the Diamantina Plateau, an area identified here as the

major Asclepiadoideae cradle of the Espinhaço Range. The Bahia portion, on the other

hand, is potentially richer in palaeomicroendemics, which are not well dispersed in the

continuous area, in keeping with the idea that Chapada Diamantina is most likely an

Asclepiadoideae museum (Fig. 6).

CAPÍTULO I – Centres of Endemism in the Espinhaço Range

25

Figure 6. Areas of endemism in the Espinhaço Range refined according to the

occurrence of exclusive species, indicating the major Asclepiadoideae cradle in Minas

Gerais (MG) and the Asclepiadoideae museum in Bahia (BA).

Acknowledgments

We thank Leilton S. Damascena and Patrícia L. Ribeiro for technical support.

This study is part of the M.Sc. thesis of CB, developed at PPGBot-UEFS, with a

fellowship from CAPES (AuxPe-PNADB). It was supported by REFLORA research

grant. AR is supported by Pq-1D CNPq grant.

CAPÍTULO I – Centres of Endemism in the Espinhaço Range

26

References

ABREU, N.L., MENINI NETO, L. & KONNO, T.U.P. 2012. Orchidaceae das Serras Negra e

do Funil, Rio Preto, Minas Gerais, e similaridade florística entre formações

campestres e florestais. Acta Botanica Brasilica 25, 58–70.

ANTONELLI, A. & SANMARTÍN, I. 2011. Why are there so many plant species in the

Neotropics? Taxon 60, 403–414.

ANTONELLI, A., VEROLA, C.F., PARISOD, C. & GUSTAFSSON, A.L.S. 2010. Climate

cooling promoted the expansion and radiation of a threatened group of South

American orchids (Epidendroideae: Laeliinae). Biological Journal of the Linnean

Society 100, 597–607.

AZEVEDO, C.O. & VAN DEN BERG, C. 2007. Análise comparativa das áreas de campo

rupestre da Cadeia do Espinhaço (Bahia e Minas Gerais, Brasil) baseada em

espécies de Orchidaceae. Sitientibus série Ciências Biológicas 7, 199–210.

BENITES, V.M., SCHAEFER, C.E.G.R., SIMAS, F.N.B. & SANTOS, H.G. 2007. Soils

associated with rock outcrops in the Brazilian mountain ranges Mantiqueira and

Espinhaço. Revista Brasileira de Botânica 30, 569–577.

BORGES, R.A.X., CARNEIRO, M.A.A. & VIANA, P.L. 2011. Altitudinal distribution and

species richness of herbaceous plants in campos rupestres of the Southern

Espinhaço Range, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Rodriguésia 62, 139–152.

BROOKS, D.R. & VAN VELLER, M.G.P. 2003. Critique of parsimony analysis of

endemicity as a method of historical biogeography. Journal of Biogeography 30,

819–825.

CASAGRANDA, M.D., TAHER, L. & SZUMIK, C. A. 2012. Endemicity analysis, parsimony

and biotic elements: a formal comparison using hypothetical distributions.

Cladistics 28, 645–654.

CONCEIÇÃO, A.A., RAPINI, A., PIRANI, J.R., GIULIETTI, A.M., HARLEY, R.M., SILVA,

T.R.S., SANTOS, A.K.A., COSME, C., ANDRADE, I.M., COSTA, J.A.S., SOUZA, L.R.S.,

ANDRADE, M.J.G., FUNCH, R.R., FREITAS, T.A., FREITAS, A.M.M. & OLIVEIRA,

A.A. 2005. Campos Rupestres. In: JUNCÁ, F.A., FUNCH, L. & ROCHA, W., Orgs.,

Biodiversidade e Conservação da Chapada Diamantina. Ministério do Meio

Ambiente, Brasília, pp. 153–180.

CRISP, M.D., LAFFAN, S., LINDER, H.P. & MONRO, A. 2001. Endemism in the Australian

flora. Journal of Biogeography 28, 183–198.

CAPÍTULO I – Centres of Endemism in the Espinhaço Range

27

CROTHER, B.I. & MURRAY, C.M. 2011. Ontology of areas of endemism. Journal of

Biogeography 38, 1009–1015.

DUTRA, V.F., GARCIA, F.C.P., LIMA, H.C. & QUEIROZ, L.P. 2008. Diversidade florística

de Leguminosae Adans. em áreas de campos rupestres. Megadiversidade 4, 117–

125.

ECHTERNACHT, L., TROVÓ, M., OLIVEIRA, C.T. & PIRANI, J.R. 2011. Areas of endemism

in the Espinhaço Range in Minas Gerais, Brazil. Flora 206, 782–791.

FIASCHI, P. & PIRANI, J.R. 2009. Review of plant biogeographic studies in Brazil.

Systematics and Evolution 47, 477–496.

FORZZA, R.C., BAUMGRATZ, J.F.A., BICUDO, C.E.M., CANHOS, D.A.L., CARVALHO JR.,

A.A., COELHO, M.A.N., COSTA, A.F., COSTA, D.P., HOPKINS, M.G., LEITMAN, P.M.,

LOHMANN, L.G., LUGHADHA, E.N., MAIA, L.C., MARTINELLI, G., MENEZES, M.,

MORIM, M.P., PEIXOTO, A.L., PIRANI, J.R., PRADO, J., QUEIROZ, L.P., SOUZA, S.,

SOUZA, V.C., STEHMANN, J.R., SYLVESTRE, L.S., WALTER, B.M.T. & ZAPPI, D.C.

2012. New Brazilian floristic list highlights conservation challenges. BioScience 62,

39–45.

GARCIA, R.J.F., LONGHI-WAGNER, H.M., PIRANI, J.R. & MEIRELLES, S.T. 2009. A

contribution to the phytogeography of Brazilian campos: an analysis based on

Poaceae. Revista Brasileira de Botânica 32, 703–713.

GARZÓN-ORDUÑA, I. J., MIRANDA-ESQUIVEL, D. R., & DONATO, M. 2008. Parsimony

analysis of endemicity describes but does not explain: an illustrated critique.

Journal of Biogeography 35, 903–913.

GIULIETTI, A.M. & PIRANI, J.R. 1988. Patterns of geographic distribution of some plant

species from the Espinhaço Range, Minas Gerais and Bahia, Brazil. In: VANZOLINI,

P.E. & HEYER, W.R., Eds., Proceedings of a Workshop on Neotropical Distribution

Patterns. Academia Brasileira de Ciências, Rio de Janeiro, pp. 39–67.

GIULIETTI, A.M., PIRANI, J.R. & HARLEY, R.M. (1997) Espinhaço Range Region,

Eastern Brazil. In DAVIS, S.D., HEYWOOD, V.H., HERRERA-MACBRYDE, O., VILLA-

LOBOS, J. & HAMILTON, A.C., Eds., Centres of Plant Diversity. A Guide and

Strategy for their Conservation, vol. 3. The Americas. WWF/IUCN, Cambridge,

397–404.

HAMMER, O., HARPER, D.A.T. & RYAN, P.D. 2009. PAST: Paleontological Statistics,

version 1.89.

CAPÍTULO I – Centres of Endemism in the Espinhaço Range

28

HARLEY R.M. 1988. Evolution and distribution of Eriope (Labiatae), and its relatives, in

Brazil. In: VANZOLINI, P.E. & HEYER, W.R., Eds., Proceedings of a Workshop on

Neotropical Distribution Patterns. Academia Brasileira de Ciências, Rio de

Janeiro, pp. 71–120.

HARLEY, R.M. 1995. Introdução. In: STANNARD, B.L., Ed., Flora of Pico das Almas –

Chapada Diamantina, Bahia, Brasil. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, pp. 43–48.

KONNO, T.U.P., RAPINI, A., GOYDER, D.J. & CHASE, M.W. 2006. The new genus

Minaria (Asclepiadoideae, Apocynaceae). Taxon 55, 421–430.

LAFFAN, S.W. & CRISP, M.D. 2003. Assessing endemism at multiple spatial scales, with

an example from the Australian vascular flora. Journal of Biogeography 30, 511–

520.

LAFFAN, S.W., LUBARSKY, E. & ROSAUER, D.F. 2010. Biodiverse: a tool for the spatial

analysis of biological and other diversity. Version 0.15. Ecography 33, 643–647.

LAFFAN, S.W., RAMP, D. & ROGER, E. 2012. Using endemism to assess representation of

protected areas – the family Myrtaceae in the Greater Blue Mountains World

Heritage Area. Journal of Biogeography 40, 570–578.

LIEDE-SCHUMANN, S. & MEVE, M. 2013. The Orthosiinae revisited (Apocynaceae,

Asclepiadoiodeae, Asclepiadeae). Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 99, 44–

81.

LIEDE-SCHUMANN, S., RAPINI, A., GOYDER, D.J. & CHASE, M.W. 2005. Phylogenetics of

the New World subtribes of Asclepiadeae (Apocynaceae – Asclepiadoideae):

Metastelmatinae, Oxypetalinae, and Gonolobinae. Systematic Botany 30, 183–194.

LONGHI-WAGNER, H.M., WELKER, C.A.D. & WAECHTER, J.L. 2012. Floristic affinities in

montane grasslands in eastern Brazil. Systematics and Biodiversity 10, 537–550.

LÓPEZ-PUJOL, J., ZHANG, F.M., SUN, H.Q., YING, T.S. & GE, S. 2011. Centres of plant

endemism in China: places for survival or for speciation? Journal of Biogeography

38, 1267–1280.

MOERMAN, D.E. & ESTABROOK, G.F. 2006. The botanist effect: counties with maximal

species richness tend to be home to universities and botanists. Journal of

Biogeography 33, 1969–1974.

MORRONE, J.J. 1994. On the identification of areas of endemism. Systematic Biology 43,

438–441.

CAPÍTULO I – Centres of Endemism in the Espinhaço Range

29

MORRONE, J.J. & ESCALANTE, T. 2002. Parsimony analysis of endemicity (PAE) of

Mexican terrestrial mammals at different area units: when size matters. Journal of

Biogeography 29, 1095–1104.

PAUTASSO, M. & MCKINNEY, M.L. 2007. The botanist effect revisited: plant species

richness, county area, and human population size in the United States.

Conservation Biology 21, 1333–1340.

PYKE, G.H. & EHRLICH, P.R. 2010. Biological collections and ecological/environmental

research: a review, some observations and a look to the future. Biological Reviews

of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 85, 247–266.

RANGEL, T.F., DINIZ-FILHO, J.A.F. & BINI, L.M. 2010. SAM: A comprehensive

application for Spatial Analysis in Macroecology. Ecography 33, 1–5.

RAPINI, A. 2010. Revisitando as Asclepiadoideae (Apocynaceae) da Cadeia do

Espinhaço. Boletim de Botânica da Universidade de São Paulo 28, 97–123.

RAPINI, A., RIBEIRO, P.L., LAMBERT, S. & PIRANI, J.R. 2008. A flora dos campos

rupestres da Cadeia do Espinhaço. Megadiversidade 4, 15–23.

RAPINI, A., VAN DEN BERG, C. & LIEDE-SCHUMANN, S. 2007. Diversification of

Asclepiadoideae (Apocynaceae) in the NewWorld. Annals of the Missouri

Botanical Garden 94, 407–422.

RIBEIRO, P.L. 2011. Filogenia e variabilidade genética de Minaria (Apocynaceae):

implicações para biogeografia e conservação da Cadeia do Espinhaço. Ph.D.

Thesis, Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana, Feira de Santana.

RIBEIRO, P.L., RAPINI, A., SILVA, U.C.S., KONNO, T.U.P., DAMASCENA, L.S. & VAN DEN

BERG, C. 2012. Spatial analyses of the phylogenetic diversity of Minaria

(Apocynaceae): assessing priority areas for conservation in the Espinhaço Range,

Brazil. Systematics and Biodiversity 10, 317–331.

SILVA, U.C.S., RAPINI, A., LIEDE-SCHUMANN, S., RIBEIRO, P.L. & VAN DEN BERG, C.

2012. Taxonomic considerations on Metastelmatinae (Apocynaceae) based on

plastid and nuclear DNA. Systematic Botany 37, 795–806.

SWOFFORD, D.L., 2000. PAUP: Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parcimony and Others

Methods, version 4.10. Sinauer, Sunderland.

VERSIEUX, L.M. & WENDT, T. 2007. Bromeliaceae diversity and conservation in Minas

Gerais state, Brazil. Biodiversity and Conservation 16, 2989–3009.

ZAPPI, D.C., LUCAS, E., STANNARD, B.L., LUGHADHA, E., PIRANI, J.R., QUEIROZ, L.P.,

ATKINS, S., HIND, N., GIULIETTI, A.M., HARLEY, R.M., MAYO S.J. & CARVALHO,

CAPÍTULO I – Centres of Endemism in the Espinhaço Range

30

A.M. 2003. Lista de plantas vasculares de Catolés, Chapada Diamantina, Bahia,

Brasil. Boletim de Botânica da Universidade de São Paulo 21, 345–398.

CAPÍTULO I – Centres of Endemism in the Espinhaço Range

31

Figure S1. Distribution of the number of collections, richness and diversity (Gini-

Simpson index) through the Espinhaço Range and its surroundings and the distribution

of the number of species endemic to the Espinhaço Range, mapped on a grid of 0.5o ×

0.5o cells.

32

CAPÍTULO II

A Cadeia do Espinhaço seria um refúgio interglacial para

a flora endêmica dos campos rupestres? Evidências da

modelagem de distribuição potencial pretérita

CAPÍTULO 2 – Modelagem da distribuição pretérita dos campos rupestres

33

RESUMO

Os campos rupestres abrigam uma flora singular, rica em endemismos, e estão concentrados

principalmente na Cadeia do Espinhaço, leste do Brasil. A Cadeia do Espinhaço é

considerada o principal refúgio para os campos rupestres durante os períodos interglaciais,

mais quentes e úmidos, quando o bioma supostamente se retrairia, ficando confinado aos

topos de morro. Para testar essa hipótese, nós modelamos a distribuição potencial pretérita

dos campos rupestres com base em 42 espécies endêmicas de Asclepiadoideae

(Apocynaceae) da Cadeia do Espinhaço. Nossas projeções mostram que a área favorável aos

campos rupestres é menor na Última Máxima Glacial (UMG) do que nos períodos mais

quentes e úmidos (Holoceno Médio e período pré-industrial), mantendo-se consideravelmente

estável na Cadeia do Espinhaço. Sendo assim, esse conjunto de serras parece representar um

refúgio glacial – e não interglacial – a condições ambientais que vêm se estabelecendo com a

diminuição global das temperaturas e da úmida desde o Mioceno. Mudanças climáticas

causadas por fatores diferentes daqueles vigentes durante o Pleistoceno, como o aquecimento

global de origem antropogênica, no entanto, poderão fazer com que a Cadeia do Espinhaço

deixe de ser um refúgio, colocando em risco a manutenção dos campos rupestres e a

preservação de sua flora endêmica.

Palavras-chave: Asclepiadoideae, mudanças climáticas, Neotrópico, Última Máxima

Glacial.

CAPÍTULO 2 – Modelagem da distribuição pretérita dos campos rupestres

34

Introdução

Os Campos Rupestres compõem um bioma formado por uma vegetação aberta geralmente

associada geralmente a solos quártzicos, em uma paisagem marcada por afloramentos

rochosos que despontam principalmente a partir de 900 m s.n.m. (Harley, 1988). Eles estão

concentrados na Cadeia do Espinhaço, no leste do Brasil (Giulietti et al., 1997), inserida entre

dois hotspots na porção sul, o Cerrado e a Mata Atlântica, e em meio às florestas

sazonalmentes secas que compõem a Caatinga na porção norte. A Cadeia do Espinhaço é o

centro de diversidade de diversas famílias de plantas (Giulietti & Pirani, 1988; Giulietti et al.,

1997; Rapini et al., 2008), abrigando mais de 1.000 espécies de angiospermas raras (Giulietti

et al., 2009; Cap. 3), o que corresponde a aproximadamente 5% das espécies endêmicas do

Brasil, estimada em 20.000 (Forzza et al., 2012). Ainda assim, a biogeografia histórica dos

Campos Rupestres tem sido pouco investigada (Hughes et al., 2013).

A principal hipótese para explicar as altas taxas de riqueza e endemismo na Cadeia do

Espinhaço está baseada em ciclos sucessivos de expansão e retração dos campos rupestres

orientados pelas oscilações climáticas do Pleistoceno. Durante os períodos interglaciais,

quentes e úmidos, haveria a expansão das florestas em direção ao topo das montanhas

paralelamente à retração dos campos, enquanto nos períodos glaciais, mais frios e secos,

haveria uma expansão dos campos para altitudes mais baixas associada à retração das

florestas (Harley, 1988; Giulietti et al., 1997). No entanto, apenas dois estudos biogeográficos

utilizaram filogenias datadas de linhagem de plantas predominantemente endêmicas da

Cadeia do Espinhaço (Antonelli et al., 2010; Ribeiro, 2011) para investigar esta questão e

nenhuma delas forneceu evidências que sustentassem múltiplos eventos de diversificação

durante o Pleistoceno. Antonelli et al. (2010) estimaram que a maior diversificação de

Hoffmannseggella (Orchidaceae) na Cadeia do Espinhaço antecedeu o Pleistoceno, enquanto

Ribeiro (2011) concluiu que ela teria acontecido em Minaria (Asclepiadoideae,

Apocynaceae) durante o Pleistoceno, mas provavelmente causado por um único evento de

diversificação.

Abordagens macroecológicas (Araújo & Williams, 2000; Jansson, 2003; Wiens &

Donoghue, 2004; Engler et al., 2004) têm sido utilizadas em investigações sobre

biodiversidade e podem contribuir para uma melhor compreensão acerca da diversificação

nos campos rupestres da Cadeia do Espinhaço. O clima é um dos aspectos mais influentes

para a evolução biológica (Erwin, 2009) e a estabilidade climática tem sido utilizada para

explicar a alta riqueza de espécies (Graham et al., 2006) e a alta diversidade genética (Hewitt,

2004) em regiões consideradas refúgios (Hughes et al., 2005; Graham et al., 2006). No

CAPÍTULO 2 – Modelagem da distribuição pretérita dos campos rupestres

35

entanto, ainda são poucos os estudos (Fjeldsa & Lovett, 1997; Araújo et al., 2008) que têm

investigado de maneira objetiva a influência histórica do clima na biogeografia de uma

região. Nesse sentido, a modelagem de nicho fornece uma excelente ferramenta para se

projetar a distribuição potencial de espécies e biomas em diferentes períodos. Áreas de

estabilidade climática emergem, então, como refúgios em potencial e passam a ter um papel

importante para o entendimento da distribuição espacial da biodiversidade em diferentes

domínios fitogeográficos neotropicais (Carnaval & Moritz, 2008; Werneck et al., 2011, 2012;

Collevatti et al., 2012).

Estimativas de distribuição geográfica a partir de simulações têm aumentado nos

últimos anos (Guisan & Zimmermann, 2000; Guisan & Thuiller, 2005; Araújo & Guisan,

2006; Peterson, 2006) e, recentemente, foram apresentados modelos de distribuição pretérita

para a floresta atlântica (Carnaval & Moritz 2008), florestas sazonalmente secas (Werneck et

al. 2011) e savanas do Planalto Central (Werneck et al. (2012), todos a partir de pontos atuais

do bioma modelado. Essa abordagem ecossistêmica, no entanto, foi criticada por Collevatti et

al. (2012), que defenderam a aplicação combinada de modelos de distribuição potencial das

espécies. Em primeira instância, é a distribuição das espécies que muda, pois são elas que

migram (não os biomas), e mudanças na composição de um bioma não necessariamente

alteram sua distribuição geográfica. Finalmente, ao assumir amplitudes de variação não

condizentes com a de uma comunidade, a abordagem ecossistêmica acaba gerando grande

incerteza.

Neste estudo, nós modelamos as distribuições de 42 espécies de Asclepiadoideae

endêmicas dos Campos Rupestres da Cadeia do Espinhaço para três diferentes períodos –

pré-industrial, Holoceno Médio e Última Máxima Glacial (UMG) – como forma de estimar a

distribuição dos campos rupestres. As projeções de distribuição histórica dos campos

rupestres nos diferentes períodos foram então comparadas para testar a hipótese de que os

topos de morro da Cadeia do Espinhaço são áreas de estabilidade climática que funcionaram

como refúgios para a flora de campos rupestres durante períodos interglaciais. Segundo esta

hipótese esperaríamos encontrar uma área favorável aos campos rupestres maior na UMG do

que no Holoceno e no presente.

Material e Métodos

Nós utilizamos os acessos de 42 espécies de Asclepiadoideae endêmicas da Cadeia do

Espinhaço (para mais detalhes, por favor, veja o Capítulo 3). As projeções de distribuição

potencial das espécies para o presente (condições pré-industriais), Holoceno Médio, há seis

CAPÍTULO 2 – Modelagem da distribuição pretérita dos campos rupestres

36

mil anos (6 k), e UMG (21 k) foram preparadas com base em seis modelos de circulação

global (MCG) obtidos a partir do CMIP5 (Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 5,

http://cmip-pcmdi.llnl.gov/) e PMIP3 (Paleoclimate Modelling Intercomparison Project

Phase 3, http://pmip3.lsce.ipsl.fr/): CCSM, CNRM, FGOALS, MIROC, MPI e MRI. Além

das variáveis climáticas, foram utilizadas altitude, a partir do HYDRO 1K

(https://lta.cr.usgs.gov/HYDRO1K), e uma variável de tipos de solo, a partir do World Soil

Information (http://www.isric.org/). Para todas as variáveis ambientais, foi utilizada uma

resolução de 5’ (aproximadamente 10 km). Nós utilizamos as 19 variáveis climáticas

disponíveis para cada modelo, condensados em componentes principais (PCA) para evitar a

multicolinearidade entre os dados ambientais, o conjunto capazes de explicar 95% da

variação foi utilizado nos modelos.

A modelagem de distribuição potencial foi realizada através do algoritmo de máxima

entropia implementado no Maxent 3.3.2 (Phillips & Dudík, 2008) para criar mapas preditivos

sobre a base de dados de ocorrências e as camadas escolhidas. Este algoritmo tem mostrado

melhor desempenho para modelagem espacial com dados apenas de presença (Wisz et al.,

2008). Além disso, é um algoritmo capaz de combinar variáveis contínuas e categóricas

(Phillips & Dudík, 2008). As estimativas de adequabilidade foram convertidas em predições

binárias através do limiar derivado da curva ROC (Reciver Operating Characteristic),

considerando favoráveis apenas áreas com valores acima do limite de corte (Elith et al.,

2006). Foram gerados 252 modelos de distribuição pretérita das espécies para cada período,

totalizando 756 modelos. Para avaliar estatisticamente o desempenho dos modelos por

espécie, nos utilizamos o true skill statistics (TSS; Allouche et al., 2006) e a área sob a curva

ROC (AUC). Foram considerados áreas de estabilidade climáticas, aquelas onde houve

sobreposição dos seis modelos para campos rupestres nos três períodos.

Resultados

Os modelos de distribuição espacial utilizaram seis eixos da PCA (Tabela 1) e apresentaram

alto desempenho (TSS e área sobre a curva ROC > 0.9). Eles foram explicados

principalmente pela litologia e pelas variáveis climáticas. A distribuição prevista para os

Campos Rupestres indica uma área menor na UMG, seguida de uma expansão no Holoceno

Médio e no período pré-industrial. Além disso, a área favorável para este bioma é menor na

porção norte da Cadeia quando comparada às áreas da porção sul. A área de estabilidade

histórica obtida a partir da sobreposição dos modelos nos três períodos equivale à área da

UMG. Ela é praticamente contínua no alto das serras, distribuída nos núcleos da Cadeia do

CAPÍTULO 2 – Modelagem da distribuição pretérita dos campos rupestres

37

Espinhaço, com variação modesta entre os períodos. Foram identificadas, também, áreas de

estabilidade nos limites da Cadeia do Espinhaço, na Serra da Canastra, a oeste e ao longo da

Serra do Mar, ao sul, entre o Rio de Janeiro e São Paulo, além dos Tepuis na Venezuela, os

Páramos na Colômbia e os Yungas no Peru (Fig. 1; Tabela 2; Fig. S1).

Tabela 1. Variáveis ambientais e eixos da análise de componentes principais usados para

modelar a distribuição das espécies de Asclepiadoideae (Apocynaceae) endêmicas dos

Campos Rupestres.

Variáveis ambientais Eixos

1 2 3 4 5 6

Bio 1 -0.333 0.118 0.096 0.114 0.038 0.072

Bio 2 0.052 0.224 -0.411 0.335 0.201 -0.427

Bio 3 -0.231 -0.124 -0.109 -0.137 0.404 -0.602

Bio 4 0.268 0.205 -0.049 0.290 -0.161 0.171

Bio 5 -0.275 0.233 0.004 0.308 -0.061 -0.042

Bio 6 -0.337 0.006 0.179 -0.029 0.001 0.029

Bio 7 0.190 0.257 -0.262 0.394 -0.071 -0.090

Bio 8 -0.284 0.166 0.060 0.235 0.143 0.237

Bio 9 -0.324 0.056 0.147 -0.005 -0.072 -0.113

Bio 10 -0.287 0.214 0.096 0.252 -0.037 0.138

Bio 11 -0.345 0.041 0.089 0.020 0.058 0.004

Bio 12 -0.153 -0.370 -0.225 0.193 -0.050 0.102

Bio 13 -0.195 -0.280 -0.322 0.018 -0.207 0.092

Bio 14 0.122 -0.319 0.310 0.294 0.099 -0.043

Bio 15 -0.172 0.154 -0.362 -0.357 -0.076 0.026

Bio 16 -0.178 -0.282 -0.358 0.047 -0.156 0.173

Bio 17 0.047 -0.361 0.270 0.313 0.141 -0.152

Bio 18 -0.005 -0.266 -0.287 0.154 0.478 0.362

Bio 19 -0.091 -0.242 -0.006 0.161 -0.630 -0.340

Porção explicada 42.290 22.632 13.294 7.685 5.987 3.135

Porção acumulada 42.290 64.922 78.216 85.902 91.889 95.024

CAPÍTULO 2 – Modelagem da distribuição pretérita dos campos rupestres

38

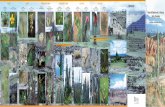

Figura 1. Áreas de estabilidade climática para os campos rupestres a partir da sobreposição

de seis modelos para três períodos: Última Máxima Glacial (21 mil anos), Holoceno Médio

(6 mil anos) e período pré-industrial.

CAPÍTULO 2 – Modelagem da distribuição pretérita dos campos rupestres

39

Tabela 2. Área (km²) favorável aos Campos Rupestres na Cadeia do Espinhaço (900 m

a.n.m.), na porção norte, na Bahia (BA), e na porção sul, em Minas Gerais (MG), bem como

a área total projetada para os Campos Rupestre na Última Máxima Glacial (21 mil anos), no

Holoceno Médio (6 mil anos) e no período pré-industrial. Foi considerado refúgio a área onde

houve sobreposição dos modelos para os três períodos.

Períodos Cadeia do Espinhaço Cadeia do Espinhaço

Campos Rupestres

BA MG

Última Máxima Glacial 54.200 23.100 31.100 515.300

Holoceno Médio 55.520 24.000 31.200 594.500

Período pré-industrial 55.900 24.700 31.200 665.700

Refúgios 54.200 23.100 31.100 471.500

Discussão

A Cadeia do Espinhaço abriga uma das floras mais singulares da América do Sul, tanto em

termos de riqueza de espécies quanto de endemismos (e.g., Giulietti et al., 2007; Rapini et al.,

2008). Sua altitude minimiza o impacto das estações secas enquanto a grande densidade de

afloramentos rochosos e a menor quantidade de gramíneas inflamáveis C4 parecem atuar

como barreiras à propagação de queimadas, fazendo dessas montanhas importantes refúgios

para plantas sensíveis ao fogo (Ribeiro et al., 2012). Com alta conservação filogenética de

nicho e baixa capacidade de dispersão, algumas linhagens acabaram tendo suas populações

isoladas em topos de morro, favorecendo o aparecimento de complexos de espécies disjuntas,

sugerindo uma irradiação não adaptativa causada por isolamentos geográficos (Ribeiro et al.,

em revisão). As amplitudes latitudinal (ca. de 1000 km) e altitudinal (900–2000) e a ampla

gama de micro-hábitats proporcionada principalmente pela grande diversidade edáfica

tornam a definição dos campos rupestres complexa; assim, o bioma é geralmente interpretado

dentre de um conceito mais amplo de cerrado. Uma das formas de se reconhecer os campos

rupestres e suas particularidades, no entanto, é a partir de suas espécies endêmicas, restritas e

altamente especializadas a ambientes encontrados exclusivamente neste bioma. Dessa

maneira, modelos baseados na distribuição dessas espécies podem indicar padrões de

distribuição ainda não revelados para o bioma.

Ao mostrar uma pequena variação na área favorável para a distribuição dos campos

rupestres entre a UMG, o Holoceno Médio e o período pré-industrial, nossas simulações de

distribuição pretérita dos campos rupestres contradizem a hipótese até então considerada pela

maioria dos autores (Harley, 1988, 1995; Alves & Kolbek, 1994; Giulietti et al., 1997; Rapini

et al., 2008), segundo a qual as terras altas da Cadeia do Espinhaço representariam refúgios

CAPÍTULO 2 – Modelagem da distribuição pretérita dos campos rupestres

40

interglaciais para a flora dos campos rupestres. Durante os períodos mais quentes a área

favorável para os campos rupestres é maior do que a UMG, e o bioma teria tido mais chances

de ampliar sua distribuição, principalmente fora da Cadeia do Espinhaço. Dessa maneira, a

Cadeia do Espinhaço parece representar um refúgio para campos rupestres durante períodos

mais frios e secos.

Como a variação da área de distribuição potencial dos campos rupestres na Cadeia do

Espinhaço não variou consideravelmente entre os últimos períodos glaciais e interglaciais, é

provável que as flutuações climáticas do Pleistoceno não tenham exercido uma influência

direta na distribuição dos campos rupestres nessa região. Dessa forma, a Cadeia do

Espinhaço, possivelmente, represente um refúgio às condições que surgiram com o clima

mais sazonal, frio e seco que se estabeleceu a partir do Mioceno, como sugerido por Ribeiro

et al. (2011, em revisão). Com a diminuição da umidade e da sazonalidade durante os

períodos interglaciais, a influência do fogo seria menor, favorecendo então a expansão dos

campos rupestres em áreas mais baixas.

A Cadeia do Espinhaço não foi considerada uma área de endemismo por Echternacht

et al. (2011) porque nenhuma das espécies endêmica analisadas por eles encontrava-se

distribuída ao longo de toda a sua extensão. Realmente, mais do que espécies endêmicas, a

Cadeia do Espinhaço apresenta uma flora rica em microendemismos. No entanto, essas

espécies frequentemente pertencem a linhagens predominantemente endêmicas desta região e

uma perspectiva filogenética é fundamental para se poder investigar este tópico com a devida

profundidade. Embora forme um refúgio coeso, a Cadeia do Espinhaço não encontra-se

completamente interligada. Reduzidas durante longos períodos a pequenas populações

isoladas em topos de morro, as linhagens restritas aos campos rupestres tendem a divergir por

deriva e raramente são reconhecidas no nível de espécie.

Apesar da área de distribuição dos campos rupestres na Cadeia do Espinhaço ter sido

pouco afetada pela amplitude das variações climáticas do último ciclo glacial-interglacial, o

mesmo pode não ocorrer no futuro. Devido à radiação solar, no passado, o aquecimento era

acompanhado por um aumento na precipitação promovida pelo aumento das temperaturas

superficiais dos oceanos, enquanto o aquecimento causado por gases do efeito estufa será

acompanhado provavelmente de uma diminuição ainda maior das precipitações na região

tropical (Liu et al., 2013). O aumento da aridez e períodos secos mais prolongados afetarão

notavelmente regiões campestres com baixa produtividade, exigindo uma reestruturação

desses ambientes (Campos et al., 2013). Simulações para o futuro indicam uma perda

considerável da área de distribuição potencial dos campos rupestres, a qual praticamente

CAPÍTULO 2 – Modelagem da distribuição pretérita dos campos rupestres

41

desaparece na porção norte da Cadeia do Espinhaço (Capítulo 3). Se a Cadeia do Espinhaço

deixar de ser um refúgio aos campos rupestres, portanto, boa parte de sua flora endêmica

estará sob risco de extinção e, sob essas novas condições, a flora da Chapada Diamantina

passa a ser a mais ameaçada.

Referências

Allouche O, Tsoar A, Kadmon R. 2006. Assessing the accuracy of species distribution

models: prevalence, kappa and true skill statistic (TSS). Journal Applied Ecology

43:1223–1232.

Alves RJV, Kolbek J. 1994. Plant species in savanna vegetation on table mountains (Campo

Rupestre) in Brazil. Vegetatio 113:125–139.

Antonelli A, Verola CF, Parisod C, Gustafsson ALS. 2010. Climate cooling promoted the

expansion and radiation of a threatened group of South American orchids

(Epidendroideae: Laeliinae). Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 100:597–607.

Araújo MB, Williams P. 2000. Selecting areas for species persistence using occurrence data.

Biological Conservation 96:331–345.

Araújo MB, Guisan A. 2006. Five (or so) challenges for species distribution modeling.

Journal of Biogeography 33: 1677–1688.

Araújo MB, Nogués-Bravo D, Diniz-Filho JAF, Haywood AM, Valdes PJ, Rahbek C. 2008.

Quaternary climate changes explain diversity among reptiles and amphibians. Ecography

31:8–15.

Campos GEP, Moran MS, Huete A et al. 2013. Ecosystem resilience despite large-scale

altered hydroclimatic conditions. Nature 494:349–353.

Carnaval AC, Moritz C. 2008. Historical climate modeling predicts patterns of current

biodiversity in the Brazilian Atlantic forest. Journal of Biogeography 35:1187–1201.

Colevatti RG, Terribile RC, Oliveira G, Lima-Ribeiro MS, Nabout JC, Rangel TF, Diniz-

Filho JAF. 2012. Drawbacks to palaeodistribution modelling: the case of South

American seasonally dry forests. Journal of Biogeography 40: 345–358.

Echternacht L, Trovó M, Oliveira CT, Pirani JR. 2011. Areas of endemism in the Espinhaço

Range in Minas Gerais, Brazil. Flora 206:782–791.

Engler R, Guisan A, Rechsteiner L. 2004. An improved approach for predicting the

distribution of rare and endangered species from occurrence and pseudo-absence data.

Journal of Applied Ecology 41:263–274.

CAPÍTULO 2 – Modelagem da distribuição pretérita dos campos rupestres

42

Elith J, Graham CH, Anderson RP et al. 2006. Novel methods improve prediction of species’

distributions from occurrence data. Ecography 29:129–51