Valores Florestais Urbanos No Canadá Pontos de Vista de Cidadãos Em Calgary e Halifax

-

Upload

natasha-ferreira -

Category

Documents

-

view

222 -

download

3

description

Transcript of Valores Florestais Urbanos No Canadá Pontos de Vista de Cidadãos Em Calgary e Halifax

U

SD

a

KEFLSUU

I

CiaaTd

nfcitsdstoosptt

ait

H

1h

Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 12 (2013) 154– 162

Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect

Urban Forestry & Urban Greening

j our na l ho mepage: www.elsev ier .de /ufug

rban forest values in Canada: Views of citizens in Calgary and Halifax

hawna C. Peckham ∗, Peter N. Duinker, Camilo Ordónezalhousie University, School for Resource and Environmental Studies, 6100 University Avenue, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada B3H 4R2

r t i c l e i n f o

eywords:nvironmental psychology

a b s t r a c t

A significant component of the urban ecosystem is the urban forest. It is also the quintessential meeting

orest managementandscape preferencetreet treesrban parksrban planning

point of culture and nature, so it is critical to incorporate values-based approaches to managing them. Thevalues that really count are those of urban citizens. A novel qualitative method was used to determinewhat qualities of the urban forest are valued by citizens of Calgary, Alberta, and Halifax, Nova Scotia,Canada. These values were compared with those reported in the literature to reveal that citizens valuethe urban forests mostly for their non-material benefits. Specifically, urban forests contribute to human

nd mo

emotional, intellectual, antroduction

Robust approaches to sustainable forest management (e.g.,anadian Standards Association, 2009) call for early and explicit

dentification of the diverse values to be satisfied through the man-gement system. In this context, values are defined simply as thosespects of the forest that are considered important to manage for.hus, values become embedded in objectives that prescribe theesired outcomes of management.

Of course, a key question is whose values dominate when alter-ative management strategies are evaluated and one is chosen

or implementation. Contemporary forest-management regimes inountries like Canada demand that diverse stakeholders, includ-ng the general populace of an area, be canvassed for, among otherhings, their expression of values to be satisfied in relation to apecific forest. Participatory processes to help steer managementirections for timber-producing forests in Canada have becometandard practice (Duinker, 1998; Beckley et al., 2006). Identifica-ion of values usually takes place as part of these processes. Oneutcome of successful values elicitation is that management pri-rities can be aligned better with values of diverse stakeholders –omething considered quite important when the forest asset is inublic ownership – rather than being aligned with the values ofhose with professional expertise such as government and indus-rial forest managers.

Whether stakeholder values are simply assumed by forest man-

gers or casually elicited as part of the participatory exercisesmplemented during planning, one might ask whether a more sys-ematic approach to values elicitation, using research protocols∗ Corresponding author at: Dalhouise University, SRES, 6100 University Avenue,alifax, NS, Canada B3H 4R2. Tel.: +1 902 494 3632.

E-mail address: [email protected] (S.C. Peckham).

618-8667/$ – see front matter © 2013 Published by Elsevier GmbH.ttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2013.01.001

ral fulfilment.© 2013 Published by Elsevier GmbH.

designed by social scientists, would yield a different value set, or atleast a value set with different priorities. This could be especiallyimportant when a forest has any kind of special characteristics. Forexample, if old-growth forest is to be managed, what value prior-ities might appropriately guide such management? Our research(Moyer et al., 2008, 2010; Owen et al., 2009) showed that citizens’values associated with old-growth forests have decidedly differentemphases than values associated with more “normal” forests.

The study reported here was motivated by this same issue inthe context of urban forests: what are the values that drive theirmanagement regimes? Put more sharply, are urban-forest man-agement regimes guided by any kind of systematic elicitation ofurban residents’ values? If one were to undertake such a system-atic elicitation, would the values align with the values that drivecontemporary urban-forest management in Canada’s cities? Urbanforest management plans in Canada today refer to an urban man-agement approach of fulfilling values (e.g. City of Victoria, 2009)with scant evidence of formal values-elicitation research in supportof their claims, especially in relation to specific urban forests.

A broad canvassing of the scholarly literature will yield aplethora of values (or benefits, or services, or functions, all of whichwe consider to be synonymous with “value” in this paper) thatresearchers have shown to be associated with urban forests (seeTable 1). Using as groupings the familiar foundational elements ofsustainable development, one can find research identifying eco-logical values (e.g., air filtration, carbon sequestration, biodiversityconservation, stormwater attenuation, temperature amelioration),economic values (e.g., enhancement of property values, energyconservation, tourism promotion), and social (including psycholog-ical) values (e.g., recreation, enhancement of community cohesion,

enhancement of physical and mental health, sense of place, gen-eral human well-being). Urban forest research of urban forestmanagement and planning gives predominance to ecological andeconomic values (e.g. Seamans, 2012), while social values are notS.C. Peckham et al. / Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 12 (2013) 154– 162 155

Table 1A comprehensive listing of urban forest values from the literature. Values listed below are summarized in Nowak and Dwyer (2007) with the exception of those valuesfollowed in another author(s) and publication year.

Category Value

Environmental

Atmospheric pollution captured through dry deposition and increase in air qualityPhytoremediation of brownfields

Moderation of microclimatic urban environment

Regulation of solar radiation into urban infrastructureWindbreakingLowering air temperature through evapotranspirationReduction of energy costs for heating and cooling greyinfrastructure

Carbon emissionsDirect carbon sequestrationControlling carbon dioxide emissions by cooling effect

Regulation of hydrological cycleReduction of the rate and volume of storm waterrunoff (increase in rainwater detention)Reduction of damage caused by floodingRegulation of water quality problems

Lowering noise levels

BiodiversityHarbouring wildlifePromoting conservation, site for environmentaleducation (Adams, 1994)

Social

Positive psychological effects

Provision of a tranquil and healthy environmentInfluencing the behaviour and performance of learnersPrivacy refugesEmotional and spiritual benefits: strong feeling ofattachment to particular places and trees

Aesthetic quality

Enhancing attractiveness of citiesBlocking of undesirable viewsSoftening of the urban hardscape (e.g., colours, shapes,textures, sounds and feelings) (Smardon, 1988)Aesthetic pleasure from the thriving of wildlife(Smardon, 1988)

Recreational spaces for communityProvision of research sites for researchers (McDonnell et al., 1997)Increase in civic values and stronger sense of communityImproved human health (Maas et al., 2006, 2009) and faster recovery from illnessReduction of crimes and fear of crime (Kuo and Sullivan, 2001)Work and labour from tree-caretaking

Economic

Increase of real estate values: residential and commercial aestheticsHigher economic activity in tree-covered areasAsset for tourism (Baines, 2000)Direct provision of timber (Baines, 2000)Recreational opportunities

wetpmrwuoi

U

cemfuibe

U

Savings on infrastructure due to environmentalservices (McPherson et al., 1999; Girling andKellett, 2002)

ell understood beyond aesthetic benefits. If, using a systematiclicitation, urban residents are asked about their values in relationo trees in the city, will the results of such research conform to theriority values evident in urban-forest management plans? Withinimal prompting and guidance, but with opportunity to expe-

ience a variety of urban-forest settings during values elicitation,e asked urban residents to tell us their thoughts about variousrban landscapes. Our purpose is therefore to report the findingsf qualitative research into citizens’ values related to urban forestsn two Canadian cities: Calgary, Alberta, and Halifax, Nova Scotia.

rban forests

There are differences of opinion between nations and expertsoncerning the concepts and definitions of urban forests thatvolved from differing historical relationships with trees and forestanagement. There is general agreement, however, that the urban

orest encompasses all natural and planted trees (including individ-al trees, as well as small groups of trees and larger stands) situated

n or near urban areas (Konijnendijk et al., 2005). Established on

oth private and public lands, each urban forest is unique and is, inssence, the dominant feature of most cities’ living landscape.Urban forests differ from hinterland forests in a number of ways.rban forests exhibit a patchy forest structure with high spatial

Carbon dioxide sequestrationAir pollutant removalDraining infrastructure

heterogeneity and often consist of both human-made landscapesand remnant naturalized areas (Nowak et al., 2001). Species com-positions of urban forests are also generally highly variable. Urbanforests may be composed of only a few species of trees or may con-tain a tremendous diversity of native and non-native tree species.Urban forests are comprised of trees of various ages and healthlevels.

It is perhaps the intensity and intricacy of human–forest inter-actions that truly distinguishes the urban forest. Trees within theurban environment are not only influenced by their biophysicalenvironment but are strongly interconnected with human activitiesand artificial infrastructure. While urban forests make importantcontributions to livable and attractive cities, they may also affectpeople’s lives negatively (e.g., as places of fear; Jorgensen et al.,2007).

Forest values

In the social sciences, values are generally defined based on theinfluential work of Rokeach (1973). He described values as cultural

ideas and judgements about what is desirable, right and appro-priate. In the broadest sense, values emerge from social dialogueand are whatever is important to us (Moyer et al., 2008). In thisresearch project, the term values will be used to describe both held156 S.C. Peckham et al. / Urban Forestry & Ur

Table 2Participant characteristics by age, sex and location.

Age (yr) City

Calgary Halifax Total

Female Male Female Male Female Male

16–30 8 7 10 10 18 1731–45 6 7 6 6 12 1346–59 2 4 3 2 5 6

va1ts

M

wpstssv

Hostrsd

pnaicawolfrysth

F

taastMAta

60+ 5 2 8 3 13 5

Total 21 20 27 21 48 41

alues (ethical principles or end states) and assigned values (rel-tive worth or preference of an object) (Rokeach, 1973; Brown,984). In a values-based approach to natural resource management,hey are the characteristics or qualities we declare important toustain (Ordonez and Duinker, 2010).

ethods

This project used a mixed-method approach to data collection,here both qualitative and quantitative data were gathered butriority was given to the former. Qualitative approaches are moreuitable for exploring values because they are grounded in the con-ext of people’s lived experiences (Burgess et al., 1988). For thistudy, the desire was to enable participants to engage all of theirenses (i.e., sight, hearing, smell, touch, and taste) actively duringisits to several urban landscapes.

We designed fourteen one-day field tours in Calgary, AB, andalifax, NS (six in Calgary and eight in Halifax), following meth-ds adapted from Owen et al. (2009). All the tours followed theame procedures and occurred during the summer months of Junehrough September 2009 on both weekends and weekdays. Theesearch day consisted of an initial survey of participants, a tour toix urban open spaces, diary writing, and an afternoon focus-groupiscussion.

Urban residents in each city were recruited to participate in theroject using various techniques including online advertisements,otices posted in high-traffic locations, local radio interviews,nd recruitment through social networks. The advertisements andnterviews explained that the purpose of the study was to gatheritizens’ thoughts on urban outdoor landscapes and did not makeny references to trees or urban forests. Still, since participantsere self-selected and trees are often an important component of

utdoor landscapes, it must be recognized that participants wereikely to have greater sensitivity to the subject. In total, 89 citizensrom a diverse range of backgrounds (i.e., age, education, urban vs.ural upbringing, number of years they have lived in city, number ofears they have lived in Canada) agreed to participate in a day-longession (Table 2). Most respondents (68%) heard about the projecthrough a friend and were university educated. Sixty-three percenteld at least one or more degree.

ield sites

With a population of 1.1 million, Calgary is the largest city inhe prairie province of Alberta. In general, Calgary’s climate is semi-rid, so groves of trees occur naturally only along the river valleysnd on the western outskirts of the city. Precipitation decreasesomewhat from west to east. Consequently, forest patches give wayo treeless grassland around the eastern city limit. Halifax Regional

unicipality (HRM), Nova Scotia, is located on the shores of thetlantic Ocean. Some 400,000 people live in the municipality but

he population is heavily concentrated in an urban core settledround the Halifax Harbour. Surrounding ocean currents create a

ban Greening 12 (2013) 154– 162

moist climate which supports a dense combination of mixed Aca-dian and coniferous forests as well as wetlands.

The urban sites chosen for the study represented the range anddiversity of landscapes one typically finds in Canadian cities. Alllocations contained trees of various ages, species, densities andhealth conditions. The project’s field sites included: (1) a residen-tial street lined with mature trees, (2) a commercial streetscapewith very few trees, (3) an athletic field with treed perimeter, (4)a forested park, (5) a naturalized schoolyard, and (6) a botanicalgarden (Table 3 and Fig. 1).

Data collection

Diaries distributed to participants at the beginning of theresearch day were used to explore the ways in which respon-dents read urban landscapes and interpret their meaning. PART Aof the diary consisted of both closed and open-ended questions togather information on participants’ opinions and usage of urbanopen spaces. PART B was divided by field site and contained only afew prompting questions related to the research topic. Participantswere specifically asked how frequently they visit the site, why theyvisit, and if and why the location is important. Each site visit lasted15 min during which each participant observed the landscape andrecorded her or his individual reflections in her or his own words.The participants answered the question, “What reflections, obser-vations, and feelings do you have about this place?” Respondentswere asked to refrain from speaking to each other during this per-sonal time. Given the possibility that the participant’s views mayshift during the research process, participants were asked to makeconcluding remarks in PART C of the diary regarding which site theyidentified with most, whether they believe their views changedthrough the research activities, and if they believe their upbringinginfluences their impressions or feelings regarding treed landscapes.

Focus-group discussions, moderated by the lead author, pro-vided further understanding of individuals’ thoughts and feelingswhile also allowing collective thought processes to occur. Sharingpersonal views within the discussion group creates an opportunityfor individuals to get in touch with their deeper feelings and con-cerns, while simultaneously being exposed to others’ viewpoints.The discussion was in essence a review of the morning tour andmany participants referred to their diaries while they shared theirthoughts and opinions about each site. With the permission of thegroup members, each focus group was audio-recorded and latertranscribed.

All diary and focus-group transcripts were coded by the leadauthor into theme areas using NVivo8, a qualitative softwarepackage (QSR International Pty Ltd, 2008). Particular attention waspaid to people’s accounts of why they felt the particular types oftreed landscapes were important to them or their community. Alist of common topics, themes and concepts was compiled andlater organized into more general value classifications. Results fromclosed questions in PART A (including demographic information)were processed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences Version16.0 (SPSS Inc., 2007). These results were later cross-referencedwith other diary data and focus-group material within NVivo8 toestablish relationships and to make comparisons. Key values wereidentified by frequency of mention (i.e., the number of times a valuewas mentioned by participants) and used to create major and minorsub-themes and categories.

Results

Participants’ diverse list of urban forest values was organizedin a table format under the broad groupings of social, envi-ronmental (or ecological), and economic values (Table 4). These

S.C. Peckham et al. / Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 12 (2013) 154– 162 157

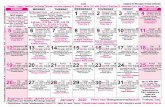

Table 3Field tour sites in Calgary, AB and Halifax, NS. The numbers in brackets indicates the chronological order of visit.

Site type Calgary location Halifax location

Mature tree-lined street (1) 7th Avenue and 2nd St, N (1) Walnut StreetCommercial streetscape (2) Centre Street, N (2) Quinpool RoadAthletic field (3) Riley Park (3) North CommonsForested natural park (4) Weaselhead Natural Area (4) Point Pleasant ParkNaturalized schoolyard (5) Altadore Elementary School (6) Dalhousie UniversityBotanical garden (6) Reader’s Rock Garden (5) Public Gardens

F comma

geaffqmv

S

t

ig. 1. Field sites in Halifax, NS and Calgary, AB: (1) mature tree-lined streets, (2)

nd (6) botanical gardens.

roupings have been used here because they are so frequentlymployed to describe the foundational elements of sustain-ble development. Additionally, each value has a correspondingrequency-of-mention class (i.e., low, moderate and high) (see Fig. 2or distribution of frequency of mention). Values with a high fre-uency of mention (e.g., >100 times) were interpreted to be valuesore commonly shared among a wide range of people relative to

alues mentioned less frequently.

ocial values

The two most striking themes to emerge from this investiga-ion are the diverse range of aesthetic values associated with urban

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

700

Fig. 2. Distribution of frequency of mention.

ercial streetscapes, (3) athletic fields, (4) forest parks, (5) naturalized schoolyards,

nature and the urban forest as a tranquil escape for improved healthand well-being. These concepts were not only the most frequentlymentioned but were also closely interrelated. The multitude of aes-thetic qualities that participants associated with the urban forestappeared to assist people to achieve positive psychological states.

Naturalness was a frequently mentioned and important char-acteristic of urban trees, as this Halifax woman commented:“I appreciate the naturalness of them. Feel they are necessaryto city dwellers’ experience in particular.” The quality of nat-uralness created a softness that people related to a friendlier,more relaxed and inviting atmosphere and provided an antithesisto or counterbalance for the hard, angular, built environ-ment characterizing most cities. For example, this Calgary mancommented:

I personally feel that Center Street could be as beautiful and asnice to spend time in as the first street [tree-lined street] thatwe went to, it would be softer, it would help society and the city.It has this cold, kind of sterile feel. It is not inviting.

The sense of naturalness provided by urban trees was also

closely associated with respondents’ feelings of stability, connec-tion to nature, and bioregional identity.Citizens valued urban forests because they offered diversity andvariety in form and function within the urban environment (e.g.,

1 y & Ur

msTddwprasr

g

TU

58 S.C. Peckham et al. / Urban Forestr

ature tree-lined streets are different in form than the naturalizedchoolyards) as well as offered a variety of experiences over time.hey attributed this to the fact that the urban forest is part of aynamic system wherein trees grow, change with the seasons, andie, to be replaced eventually by new growth. This partly explainshy respondents appreciated densely forested parks as stimulatinglaces that fascinated, energized and motivated, as this Calgary manemarked: “This is the kind of place you can just go and wandernd discover new things, a broken log, a cool inlet, etc. I like the

ense of discovery.” These more-natural landscapes also inspiredespondents’ creativity, imagination, and curiosity.Respondents derived pleasure from seeing many shades ofreen and often spoke of their appreciation of vistas overlooking

able 4rban forest values in Calgary, AB and Halifax, NS. Frequency of mention: white = low (1–

Value category Value Artistic expression Barrier, buffer Beauty Colour Dimension Grace Naturalness Nature-infrastructure balance

Pattern Quality of light Shade Large, grandeur Size and scale Small Fresh Smell Quiet Leaves in the windBirds

Sounds

Animals Softness Texture Shape, form Variety

Views, vistas

Aesthetics

Wind break Environmental impEcological

consciousness Nature appreciation

Accessible Interactive

Educational

Nature experience Native flora and fa

Harmony Diversity acceptance

Distribution, accesEquity Future generations Self limit, restraintIntrinsic

Natural treasure Respect

Moral

Cared for, clean Stewardship Affection Connection to nature Dynamics Enjoyment Friendliness, welcome

Escape, refuge Freedom Choice

Hope

Social

Psychological

Humility

ban Greening 12 (2013) 154– 162

forested parks or views of green from office or home windows.Commuting through the city, they preferred using areas with treesor other green vegetation over transportation corridors dominatedby concrete (e.g., commercial streetscapes). Participants felt lessdistracted and mindful in the presence of large trees, as this Halifaxwoman explained: “It [the forested park] makes one want to sit andponder, to focus on the moment.” Many respondents commentedthat cars appeared to travel at slower speeds on the mature-treelined streets, leading them to feel safer.

Perhaps most surprising was the high frequency with whichparticipants mentioned sounds specifically related to trees. Theydescribed their delight in hearing tree leaves rustling in the windand the sounds of birds calling above their heads, as one Halifax

49), grey = moderate (50–99), black = high (100–450).

Frequency

act

una

s

S.C. Peckham et al. / Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 12 (2013) 154– 162 159

Table 4 (Continued)

Value category

Mental health Mental Reflecti on Romance

Enclosed, surrounding Safety Shelter, protection

Comfort

Stability Character Familiarity Home

Sense of place

Landmark, icon Slower pace Peacefulness

Solitude Spirit ual

Awe, fascination Creativity, imagination Curiosit y, explorati on Inspirati on, moti vati on

Stimulating

Variabilit y

Communit y Famil y

History Cult ural Memorial Nostalgia Memory Reminiscent Options Good place to live

Rec reati on

Air purification, freshness Air quality Oxygen production Diversit y Habit at, wil dli fe Biodiversit y Nature preservati on

Carbon storage Clean water Ecologica l process es Nutrient cycles Growth Aliveness

Human li fe-suppo rt

Env ironmental

Temperature ameli orati on

Lower healt h ca re expendit ures

wahwoshbficoiso

Increa sed rea l estate values Economic Tourism

oman remarked: “I love that sound, the shimmering of the leavesnd I love that I can hear the chickadees. I feel a part of it all, good,appy, relaxed.” These sounds produced a sensory experience thatas calming and peaceful, leading to a reflective state and a feeling

f ease and of connectivity to nature. Additionally, large or densetands of trees created a physical and psychological buffer from theustle and bustle, resulting in a sense of freedom from the usualusyness of the city. A Halifax woman explained the role the urbanorest plays in her life: “My reason for coming to a place like thiss, in a way, something I do to escape the hectic mayhem of theity.” Participants valued urban landscapes where trees enclosed

r surrounded them because these were perceived to be welcom-ng and quieter, and provided them with much needed solitude andeparation from a hectic urban environment. Overarching branchesf the tree canopy were often associated with respondents’ feelingsof being sheltered and protected, as this Halifax man commented:“[T]he tree-lined street kind of closed over you and kind of huggedyou.”

Respondents often described landscapes with numerous, large,healthy trees as good places to live because they made a place feelestablished and stable, cared for, safe, and imbued with character.Big, old trees also connected many respondents to the past as theyconsidered what changes may have occurred within the commu-nity during the trees’ lifetime, and as they reminisced about playingaround large trees as children. Because of this connection to thepast, many citizens felt nostalgic during visits to the mature tree-

lined streets and forested parks. A Halifax woman over 60 years ofage described her family’s weekend outing: “[W]e used to go weekafter week and take a picnic lunch, we could not afford to eat out, wenever even thought about eating out, and just spent practically all1 y & Ur

otsb

httictfmi

fthswewprsivs

(ta“hMipdfpaga

imstmtef

iapiftrbetbor

60 S.C. Peckham et al. / Urban Forestr

f Sunday there.” In contrast, respondents remarked that a lack ofrees or the presence of unhealthy trees, such as on the commercialtreetscapes, made the locations feel sterile, unsafe, and neglectedy urban society.

Participants recognized many forested sites as important localistorical landmarks, memorials, and cultural experiences, addinghat important cultural events still take place there. Some par-icipants identified specific forested landscapes as extraordinarilymportant because so much of their personal history, from earlyhildhood to old age, had unfolded in these locations. Two par-icipants, who before the research day had never met, chose theorested park in Halifax as the final resting place for their family

embers’ ashes despite municipal by-laws prohibiting this activ-ty.

There were over 400 references to the importance of the urbanorest for recreation. The most valued urban landscapes were thosehat offered the greatest diversity of activities and were close toome. For example, athletic fields were regarded as less attractiveites for recreation than more densely forested landscapes because,hile they were excellent for formal sport (e.g., soccer, baseball,

tc.), they prevented so many other social activities (e.g., a quietalk with a friend) from taking place around the area. Partici-ants recognized that people in general prefer different types ofecreational activities at different stages of their lives, such as theenior-aged participants who were no longer interested in partic-pating in sports such as football or soccer. Thus, the provision ofarious forms of urban forest conditions for different members ofociety was important.

Overall, respondents described that the large forested parksWeaselhead and Point Pleasant Park) provided more opportunitieso engage in a diverse range of both passive and active recre-tion, as is illustrated by this Calgary respondent’s diary entry:“FREEDOM!” So much to do in a place like this. Fly kite, bike,ike, picnic, birding, meditate, canoe. Did I mention freedom?”ost city forests are primarily used for walking, running or bik-

ng, but many respondents also enjoy opportunities to geo-cache,icnic, read, or pause for reflection. These citizens felt that chil-ren should have access to a variety of safe outdoor environmentsor play and exploration. The varied topography and diversity oflants within densely treed urban landscapes were pointed outs allowing for more imaginative play and adventure, as a Cal-ary woman commented: “This place makes me feel like I am in

storybook!”Athletic parks, forested parks, and botanical gardens played an

mportant role in the lives of these urbanites as places to gather,eet, and socialize. Some participants even enjoy visiting these

ites to sit and observe other people. Respondents also highlightedhe value of these landscapes for isolated members of their com-

unity, such as seniors and mothers of young children, becausehey provide safe places to get out of the home and be with oth-rs. Forested parks in particular were viewed as quality sites foramilies to spend time together.

For participants, spending time in nature is tremendouslymportant and 94% of them rely on local forested parks for nearbyccess to nature experiences. As mentioned above, respondentserceived naturalized forested areas within the city as provid-

ng a more stimulating, non-controlled environment where theyelt free to interact and engage with natural elements. Withinhese places, many respondents felt better able to gain an expe-iential sense of oneness with the natural world, which someelieved can lead to both an awareness and appreciation ofcological systems or to develop an ecological consciousness, par-

icularly in children. Equally important, a number of participantselieved that this intimate contact with nature allowed them tobserve directly how their behaviours affected the local envi-onment and that this information encouraged better personalban Greening 12 (2013) 154– 162

decision-making regarding the environment, as this Calgarywoman explained:

[T]hat is why I think that [naturalized schoolyards] are so impor-tant because they give kids the idea of what the real world is like,that there are animals and seeing how things grow and thingschange and how you can affect that process.

Some participants’ comments demonstrated that they valuedany natural elements within the urban environment for the sim-ple fact of its existence. Others noted that the well-cared for andpopular forested parks were unique, special places or natural “trea-sures” within their city. Many urban citizens believed that sparselyplanted, unhealthy trees, litter, and a lack of well-maintainedwalking trails or benches represented a lack of responsibility,respect, and communal care of the natural environment. Onthe contrary, if the landscape contained robust, old trees anda diversity of vegetation, then many participants thought thatthe site symbolized acceptance, respect, and appreciation for thenatural world and were essentially physical representations ofa balanced human–nature relationship, as this Halifax womanexplained: “They [forested parks] are more representative of peo-ple trying to work with nature rather than against it.” Thisconcept is also reflected in comments from this Calgary partici-pant:

My most ‘awe’ feeling and connection to nature was at themature tree-lined street. The mixture of human architecture andnature made for a very cool effect. I really felt that nature andhumanity were living beside each other in peace.

Environmental values

Respondents acknowledged that the urban forest is importantfor ecological life-support. However, overall this value categorywas mentioned with much less frequency than other urban-forestbenefits. Additionally, not all forms of the urban forest wererecognized equally as contributing to ecological life-support func-tions. For example, citizens recognized the contribution urbantrees make to improving air quality, providing shade, and creat-ing habitat for birds yet only naturalized forest stands (as opposedto street plantings) were valued for preserving nature, cyclingnutrients, providing biodiversity, maintaining ecological processesand services, and creating habitat for other wildlife. The oneexception is that the botanical gardens were also appreciatedfor their biodiversity, particularly their plant diversity. Interest-ingly, only one Halifax respondent among all the participantsin either city spoke about the value of urban trees as carbonsinks.

Economic values

Few participants mentioned economic values of the urban for-est. Only seven references were made by Calgary and Halifaxparticipants to increased property values for urban real estate con-taining healthy trees or located nearby a forested park. Urban treesas a tourist attraction, such as trees in a botanical garden, elicitedfewer than ten references. A significantly higher number of respon-dents described the importance of the urban forest for improvingcitizen’s health which can lower local health-care expenditures, asthis Calgary man explained:

Treed cities are extremely important. They give the people a

place to play, exercise, relax, enjoy each other’s company awayfrom the hustle and bustle. Helps keep them healthy and out ofthe hospitals. Probably keep my taxes down if people got outmore and met the trees.”y & Ur

D

roOqelrebiatpftr1twt

ufisbtapcass

aafthctto(utse

ullwgFprtesltft

S.C. Peckham et al. / Urban Forestr

iscussion

Comparing the results of this investigation with our literatureeview (Table 1) reveals a discrepancy in both the type and numberf benefits categorized under economic and ecological life-support.ur respondents frequently identified wildlife, biodiversity, and airuality as important forest attributes, yet no participant mentionedcological life-support values related to regulation of the hydro-ogical cycle or moderation of the urban microclimate. Similarly,educed health-care costs, increased tourism, and increased realstate values were recognized, even if infrequently, as economicenefits of urban forests yet timber provision or the economic sav-

ngs incurred through removal of air pollution, CO2 sequestration,nd reduced heating and cooling costs were never mentioned byhis study’s participants. This may be due to the fact that manyeople simply do not bring these benefits of urban trees to the fore-ront of their minds when unprompted to do so, or are unaware ofhe diversity of economic benefits derived from city trees or theole urban forests play in ecosystem functioning (Xu and Bengston,997; Kellert, 2005). We speculate that this may also be the case forwo other values not mentioned by participants in this project buthich were identified in the literature: (1) research sites for scien-

ific study, and (2) work and labour derived from tree-caretaking.What people really expressed appreciation for in relation to

rban forests are the aesthetic, psychological, and moral bene-ts provided by nearby access to nature. This contact with naturalystems greatly affected urban citizens’ physical and mental well-eing and while this may not be new knowledge, we suggest thathese values are under-appreciated in urban forest master plansnd management programmes. The research method used in thisroject (i.e., a diary format) provided a highly refined and detailedatalogue of urban forest qualities that people valued in their city,nd reveals that a strong relationship exists between these multi-ensory qualities and positive effects on participants’ psychologicaltates.

The psychological benefits of nature experiences within citiesre reasonably well studied (Ulrich, 1984; Chiesura, 2004; Herzognd Strevey, 2008; Konijnendijk, 2008), mostly noting that urbanorests enhance human well-being. Urban forests also offer a con-rast to dense urbanization and visually block or soften the urbanardscape. Thus, urban forests provide a welcome reprieve fromontrolled city environments. The naturalness of urban trees andhe sounds associated with trees also contributed to people’s abilityo sense a connectedness to nature, which can lead to developmentf an ecological consciousness (Peckham, 2011). Bunce and Desfor2007) suggested that natural elements like urban trees are val-ed because of what they are in themselves, societal imageries ofhe non-human environment. This project’s findings also demon-trate that urban residents endow the urban forest with rich social,ducational, and moral meaning.

The meanings assigned to urban forests at large are somewhatnique from person to person. For participants in this study, treed

andscapes such as forested parks, naturalized parks, and tree-ined streets represented nature conservation, human coexistence

ith nature, environmental stewardship, and an opportunity toain awareness of natural processes, cycles, and seasonal change.orested parks were also significant to many of this study’sarticipants as places of memorial and memory. Our literatureeview (Table 1) highlights the contributions urban forests makeo increasing civic values and stronger sense of community (Coleyt al., 1997; Kuo and Sullivan, 2001), as well as the emotional andpiritual benefits derived from feelings of attachment to particu-

ar places and trees (Dwyer et al., 1991; Chiesura, 2004). However,here appears to be a lack of recognition of urban forests as placesor learning about nature, or the contribution urban trees makeowards enhancing environmental values.ban Greening 12 (2013) 154– 162 161

Conversely, many respondents associated uneven tree distribu-tion throughout their city of residence, a lack of species diversity,and unhealthy or uncared-for trees on streetscapes as character-istics of the urban forest that underlined social pathologies anddisparities. This finding is similar to urban forest research con-ducted by Heynen et al. (2006). Urban forestry programmes need torespond to contemporary social issues such as disparate access toa healthy urban forest among community groups. To address theseissues, the demands and ideas held by an increasingly multicul-tural urban population, as well as other marginalized groups suchas women, the disabled, the elderly, and the unemployed, need tobe better understood and considered during the planning process(Johnston and Shimada, 2004).

Urban trees were mostly valued by respondents because theyprovided peacefulness, comfort, escape, beauty, naturalness, a con-nection to nature, biodiversity, a sense of history, and a preferredenvironment for family and community. This finding that peoplemention more frequently the less-tangible values than they dothe more tangible (material) values is congruent with results ofresearch by Sommer et al. (1990), Schroeder and Ruffolo (1996)and Schroeder et al. (2006).

The implications of these results on the sustainable manage-ment of urban forests are important. To be successful, sustainableurban forest management must reflect urban society’s values whichessentially strike at the heart of want we want and what we believeis important (Ordonez and Duinker, 2010). Focusing on a narrowrange of physical and material benefits of the urban forest betrays alack of appreciation of other values of urban trees that are indepen-dent of human material interests, such as love of nature, reverenceof its beauty, or being inspired by its spiritual qualities. Our researchconfirms that urban trees, as citizens understand the trees throughtheir senses and knowledge-building processes, help improve per-sonal outlooks, attitudes, and senses of well-being. As revealed bycitizen expression in our data, the social values of urban trees areforemost on people’s minds.

Urban forests can be carefully developed and shaped to promoteharmonious urban ecosystems, thus accommodating a diversity ofdesirable social, environmental, and economic values. This mustoccur, however, in close collaboration with those who are themain users of urban forests – city dwellers. We acknowledge thatour qualitative approach has limitations, such as a likely self-selection bias, and the fact that the considerable time and expenseinvolved in touring participants may discourage municipal treeagencies from implementing this approach. However, this projectwas funded by a federal granting council and implemented byuniversity researchers, so municipal tree agencies could partnerwith the research community to reduce costs of acquiring suchdata. Qualitative methods such as those employed in this researchprovide in-depth information regarding how people perceive theenvironment whilst directly experiencing it.

This study created additional empirical insight into the non-material values associated with two Canadian urban forests. Whilesocial values may present greater measurement challenges thando environmental and economic values, they are undeniably andprofoundly important in our society (Xu and Bengston, 1997;Johnston and Shimada, 2004). In our view, researchers, urban-forest professionals, and policy-makers need to balance theirhyper-attentiveness to the environmental and economic benefitsof urban forests with careful and considerate attention to the socialvalues that urban citizens have at the forefront of their minds. Webelieve that it is not enough simply to invite citizens into meetingrooms to look at and respond to professionally developed plans for

urban-forest development. Much deeper insight into the ways thaturban residents appreciate the trees around them is required, andthat can only come from values-elicitation research. Such researchis best undertaken in the context of the urban outdoors, where the1 y & Ur

tevt

A

Sgt

R

A

BB

B

B

B

C

C

C

D

D

G

H

H

J

J

K

K

62 S.C. Peckham et al. / Urban Forestr

rees grow, rather than the meeting hall. Only when all parties cel-brate together the rich and diverse ways in which urban residentsalue the trees in the city can their management follow a pathwayowards sustainability.

cknowledgements

We acknowledge financial support for the project from theocial Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada andive a special thanks to all the research participants for giving theirime and energy to provide personal thoughts and feelings.

eferences

dams, L.W., 1994. In our own backyard: conserving urban wildlife. Journal ofForestry 92, 24–25.

aines, C., 2000. A forest of other issues. Landscape Design 294, 46–47.eckley, T.M., Parkins, J.R., Sheppard, S.R.J., 2006. Public Participation in Sustain-

able Forest Management: A Reference Guide. Sustainable Forest ManagementNetwork, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB.

rown, T., 1984. The concept of value in resource allocation. Land Economics 60,231–246.

unce, S., Desfor, G., 2007. Introduction to “Political ecologies of urban waterfronttransformations”. Cities 24 (4), 251–258.

urgess, J., Harrison, C.M., Limb, M., 1988. People, parks and the urban green: a studyof popular meanings and values for open spaces in the city. Urban Studies 25,455–473.

anadian Standards Association, 2009. Sustainable Forest Management. Z809-08.Canadian Standards Association, Mississauga, ON.

oley, R.L., Kuo, F.E., Sullivan, W.C., 1997. Where does community grow? The socialcontext created by nature in urban public housing. Environment and Behavior29, 468–492.

hiesura, A., 2004. The role of urban parks for the sustainable city. Landscape andUrban Planning 68 (1), 129–138.

uinker, P.N., 1998. Public participation’s promising progress: advances in forestdecision-making in Canada. Commonwealth Forestry Review 77 (2), 107–112.

wyer, J.F., Schroeder, H.W., Gobster, P.H., 1991. The significance of urban trees andforests: toward a deeper understanding of values. Journal of Arboriculture 17(10), 276–284.

irling, C., Kellett, R., 2002. Comparing stormwater impacts and costs on threeneighborhood plan types. Landscape Journal 21 (1), 100.

erzog, T.R., Strevey, S.J., 2008. Contact with nature, sense of humor, and psycho-logical well-being. Environment and Behavior 40 (6), 747–776.

eynen, N., Perkins, H.A., Roy, P., 2006. The political ecology of uneven urbangreen space: the impact of political economy on race and ethnicity in pro-ducing environmental inequality in Milwaukee. Urban Affairs Review 42 (1),3–25.

ohnston, M., Shimada, L.D., 2004. Urban forestry in a multicultural society. Journalof Arboriculture 30 (3), 185–191.

orgensen, A., Hitmough, J., Dunnett, N., 2007. Woodland as a setting for housing-appreciation and fear and the contribution to residential satisfaction and placeidentity in Warrington New Town, UK. Landscape and Urban Planning 79,

273–287.ellert, S.R., 2005. Building for Life: Designing and Understanding theHuman–Nature Connection. Island Press, Washington, DC.

onijnendijk, C.C., Nilsson, K., Randrup, T.B., Schipperijn, J. (Eds.), 2005. Urban Forestand Trees. Springer, Berlin.

ban Greening 12 (2013) 154– 162

Konijnendijk, C.C., 2008. The Forest and the City: The Cultural Landscape of UrbanWoodland. Springer Science and Business Media, New York, NY.

Kuo, F.E., Sullivan, W.C., 2001. Environment and crime in the inner city: does vege-tation reduce crime? Environment and Behavior 33 (3), 343.

Maas, J., Verheij, R.A., Groenewegen, P.P., De Vries, S., Spreeuwenberg, P., 2006. Greenspace, urbanity, and health: how strong is the relation? Journal of Epidemiologyand Community Health 60, 587–592.

Maas, J., Verheij, R.A., De Vries, S., Spreeuwenberg, P., Schellevis, F.G., Groenewe-gen, P.P., 2009. Morbidity is related to a green living environment. Journal ofEpidemiology and Community Health 63, 967–973.

McDonnell, M.J., Pickett, S.T., Groffman, P., Bohlen, P., Pouyat, R.V., Zipperer, W.C.,Parmelee, R.W., Carreiro, M.M., Medley, K., 1997. Ecosystem processes along anurban-to-rural gradient. Urban Ecosystems 1 (1), 21–36.

McPherson, E.G., Simpson, J.R., Peper, P.J., Xiao, Q., 1999. Benefit–cost anal-ysis of Modesto’s municipal urban forest. Journal of Arboriculture 25,235–248.

Moyer, J.M., Owen, R.J., Duinker, P.N., 2008. A forest-values framework for old-growth. The Open Forest Science Journal 10, 37–53.

Moyer, J.M., Duinker, P.N., Cohen, F.G., 2010. Old-growth forest values: a nar-rative study of six Canadian forest leaders. Forestry Chronicle 86 (2),256–262.

Nowak, D.J., Noble, M.H., Sisinni, S.M., Dwyer, J.F., 2001. People and trees: assessingthe US urban forest resource. Journal of Forestry 99 (3), 37–42.

Nowak, D.J., Dwyer, J.D., 2007. Understanding the benefits and costs of urban forestecosystems. In: Kuser, J.E. (Ed.), Urban and Community Forestry in the Northeast., 2nd ed. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, pp. 25–46.

Ordonez, C., Duinker, P., 2010. Interpreting sustainability for urban forests. Sustaina-bility 2, 1510–1522.

Owen, R.J., Duinker, P.N., Beckley, T.M., 2009. Capturing old-growth values for usein forest decision-making. Environmental Management 43, 237–248.

Peckham, S.C., 2011. Nature in the City: Ecological Consciousness DevelopmentAssociated with Naturalized Urban Spaces and Urban Forest Values in Cal-gary, AB and Halifax, NS. Unpublished Master’s Thesis. School for Resourceand Environmental Studies, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS. Retrieved fromhttp://dalspace.library.dal.ca//handle/10222/13180

QSR International Pty Ltd, 2008. NVivo 8 [Computer software]. QSR InternationalPty Ltd., Victoria, Australia.

Rokeach, M., 1973. The Nature of Human Values. The Free Press, New York, NY.Schroeder, H.W., Ruffolo, S.R., 1996. Householder evaluations of street trees in a

Chicago suburb. Journal of Arboriculture 22, 35–43.Schroeder, H.W., Flannigan, J.D., Coles, R., 2006. Residents’ attitudes toward street

trees in UK and USA communities. Arboriculture and Urban Forestry 32,236–246.

Seamans, G.S. (2012). Mainstreaming the environmental benefits of street trees,Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, In press.

Smardon, R.C., 1988. Perception and aesthetics of the urban environment:review of the role of vegetation. Landscape and Urban Planning 15 (1),85–106.

Sommer, R., Guenther, H., Barker, P.A., 1990. Surveying householder response tostreet trees. Landscape Journal 9, 79–85.

SPSS Inc., 2007. Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), Version 16.0. SPSS Inc.,Chicago, IL.

Ulrich, R., 1984. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery.Science 224 (8), 4647, 420–421.

Victoria, City of, 2009. City of Victoria urban forest master plan (draft). In: Gye andAssociates Urban Forestry Consultants Ltd. (G&A); Judith Cullington & Asso-

ciates. (Ed.) G&A; City of Victoria: Victoria, BC, Canada, 63, Retrieved from:http://www.victoria.ca/cityhall/departments compar rbnfrs.shtmlXu, Z., Bengston, D.N., 1997. Trends in national forest values amongst forestry profes-sionals, environmentalists, and the news media, 1982–1993. Society & NaturalResources 10, 43–59.