INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE PESQUISAS DA AMAZÔNIA – INPA ...€¦ · SARA DEAMBROZI COELHO Manaus,...

Transcript of INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE PESQUISAS DA AMAZÔNIA – INPA ...€¦ · SARA DEAMBROZI COELHO Manaus,...

11111111111111

INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE PESQUISAS DA AMAZÔNIA – INPA

PROGRAMAS DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO DO INPA

ESTUDO DA RELAÇÃO ENTRE OS TAMANHOS POPULACIONAIS DAS ESPÉCIES

ARBÓREAS NA AMAZÔNIA E SEUS USOS PELOS HUMANOS

SARA DEAMBROZI COELHO

Manaus, Amazonas Julho, 2018

ii

SARA DEAMBROZI COELHO

ESTUDO DA RELAÇÃO ENTRE OS TAMANHOS POPULACIONAIS DAS ESPÉCIES

ARBÓREAS NA AMAZÔNIA E SEUS USOS PELOS HUMANOS

Orientadora: Juliana Schietti

Dissertação apresentada ao Instituto Nacional de

Pesquisas da Amazônia como parte dos requisitos

para obtenção do título de Mestre em Ecologia.

Manaus, Amazonas Julho, 2018

iii

Ficha catalográfica

Agradecimentos

C672 Coelho, Sara Deambrozi Estudo da relação entre os tamanhos populacionais das espécies

arbóreas na Amazônia e seus usos pelos humanos / Sara Deambrozi Coelho. - Manaus: [s.n.], 2018.

- f. : il. Dissertação (Mestrado) - INPA, Manaus, 2018. Orientador : Juliana Schietti. Programa: Ecologia.

1. Árvores - Amazônia. 2. Ecologia histórica na Amazônia. 3. Etnobotânica. I. Título.

CDD 582.16

Sinopse:

Estudou-se a relação entre o tamanho populacional das espécies arbóreas na Amazônia e

seus usos pelos humanos. Os conhecimentos etnobotânicos e ecológicos foram

integrados, baseados em décadas de registros de inventários florísticos e informações

sobre os usos das plantas, documentados e coletados por toda Amazônia.

Palavras-chave: hiperdominância, etnobotânica, ecologia histórica, plantas úteis

iv

Um longo caminho foi percorrido até a conclusão deste trabalho, pelo qual diversos atores

compuseram a estória deste capítulo e tornaram possível a realização, consolidação e

conclusão deste trabalho.

Agradeço à Juliana Schietti por ter sido uma ótima orientadora! Sempre motivada, me ajudou

muito a amadurecer e interpretar as ideias e os resultados deste trabalho e foi fundamental na

consolidação dele.

E para compor o trio perfeito na (des)orientação, também devo um grande agradecimento ao

Charles Clement, quem me (des)orientou com excelência com sua grande sabedoria! Também

agradeço à Carolina Levis pelas inspiradoras conversas, apoios e ideias que me conduziram e

também foram fundamentais desde o primeiro momento quando ainda pensávamos no projeto

até sua conclusão.

À Marielos Peña-Claros, quem juntamente idealizou as principais questões norteadores deste

trabalho. Agradeço pelas discussões iniciais e pela participação no fechamento deste trabalho.

Ao André Junqueira pelas ideias iniciais sobre o projeto. Agradeço também por me apresentar

as florestas antropogênicas, seus atores e arte-fatos espalhados pelos quintais, roças e florestas

do Madeira.

Ao Bernardo Flores pelas discussões e chuva de ideias a partir dos resultados preliminares.

Ao Fabrício Baccaro e Fernando Figueiredo (Nando) pela grande paciência em me orientar

nas estatísticas, gráficos e R. Ao Hans ter Steege pelas ideias e comentários sobre os métodos,

resultados e discussão deste trabalho.

Ao André Antunes pelas inúmeras discussões sobre o trabalho e sobre a Amazônia e suas

histórias contadas pelos moradores das florestas, livros e papeis velhos e pelo

companheirismo.

Aos professores do PPG – Ecologia pelas aulas e ensinamentos sobre Ecologia e um pouco da

Amazônia. Também aos professores Gilton Mendes, Claide de Moraes, Glenn Shepard e à

professora Ana Carla Bruno pelos ensinamentos sobre a Amazônia domesticada e os povos

das florestas.

À Família Vegetal, especialmente à Flávia Costa, pelas discussões inspiradoras sobre os

trabalhos.

Às e aos desorientada(o)s da domesticação, especialmente Maju, Rubs e Olivinha que sempre

estiveram por perto! Agradeço por todas as parcerias, presenças, conversas, trocas e apoios

sempre.

v

À Capoeira Angola FICA, especialmente ao Gunter, pelos constantes ensinamentos e

fundamentos da capoeira, sempre muito especial para mim.

Às Famílias Vila do Chaves e Casa da Sopa, por me receberem tão bem nos lares por onde

passei. Aos amigos e amigas Aline, Gi, Laura, Minhoca, Dani, Marisabel, Marquinhos,

Marina, Clara, Lis, Mari Cassino e Caetano. À turma do mestrado.

Aos povos das florestas e a todos os moradores e moradoras das comunidades que nos

receberam para nos contar um pouco sobre suas histórias e as sobre as histórias ouvidas e

vividas das florestas, roças, plantas e cacos.

À minha família, mãe, pai e irmão, por todo e imenso apoio e amor!

vi

Resumo Por mais de 13.000 anos os habitantes da Amazônia têm usado as plantas da floresta. Hipóteses

sobre a associação entre a abundância das plantas e seus usos sugerem que (i) a disponibilidade

da planta influencia seus usos ou que (ii) os usos influenciam a abundância de plantas úteis nas

florestas modernas por meio de atividades antropogênicas de longo prazo. A relação entre a

utilidade de espécies arbóreas e o tamanho de suas populações em florestas amazônicas na

escala continental é desconhecida. Aqui mostramos que as florestas amazônicas são dominadas

por espécies arbóreas úteis, que correspondem pelo menos 2326 espécies e 90% das espécies

hiperdominantes. Nosso modelo prevê que as espécies hiperdominantes têm pelo menos 80%

de chance de serem úteis, enquanto as não-hiperdominantes têm pelo menos 9 %. As categorias

de uso as quais a supressão de indivíduos é mais frequente, como construção e lenha, não estão

associadas às espécies com menores tamanhos populacionais. Espécies incipientemente

domesticadas são as mais dominantes nas florestas amazônicas, enquanto as espécies

totalmente domesticadas são menos abundantes. Nossas análises elucidam a grande utilidade

das florestas amazônicas, embora essa utilidade pareça invisível hoje, o que explica porque as

florestas estão sendo eliminadas para fornecer gado e grãos aos mercados mundiais.

vii

Abstract

Useful arboreal species dominate Amazonian forests

For more than 13,000 years, Amazonia’s inhabitants have been using forest plants. Hypotheses

about the association between plant abundance and their use suggest either that plant

availability influences uses or that use influences abundance of useful plants in modern forests

via long-term human activities. The relationship between usefulness of arboreal species and

their population sizes in Amazonian forests at the continental-scale is, however, unknown. Here

we show that Amazonian forests are dominated by useful arboreal species, which include at

least 2326 species. Our model predicts that hyperdominant species have at least 80 % chance

to be useful, whereas non-hyperdominants have only 9 % chance of being useful. Incipiently

domesticated species are the most abundant in Amazonian forests, whereas domesticated

species are less abundant. Our analyses elucidate the enormous usefulness of Amazonian

forests, although this usefulness seems invisible today, which may explain why the forests have

been destroyed to supply cattle and grain to world markets.

viii

Sumário

Lista de figuras ...................................................................................................................... 1

Introdução ............................................................................................................................. 2 Objetivos ............................................................................................................................... 3

Capítulo 1 – Useful arboreal species dominate Amazonian forests ......................................... 4 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 6 METHODS ........................................................................................................................ 8 RESULTS........................................................................................................................ 14 DISCUSSION .................................................................................................................. 22 REFERENCES ................................................................................................................ 28 SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS ................................................................................ 33

Conclusão ............................................................................................................................ 50

11111111111111

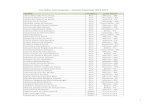

Lista de figuras Figura 1. Location of the ethnobotanical studies of useful arboreal species in the Amazon

Basin and Guiana Shield.

Figura 2. (a) Species accumulation curve of useful woody species documented in Amazonia,

based on 29 ethnobotanical studies during the period 1926-2013; (b) Species accumulation

curve showing the 29 studies ordered by contribution of new species and the total number of

useful species that each study contributed to the dataset.

Figura 3. Relationship between the mean population sizes of useful and non-useful arboreal

species in Amazonia.

Figura 4. (a) Logistic regression that shows the probability of species being useful according

to their population size; (b) Species abundance rank.

Figura 5. Relationship between the mean population sizes of arboreal species and their use

categories.

Figura 6. (a) Mean population sizes among the use categories and degree of domestication;

(b) Relationship between population mean size and their frequency in the landscape (number

of plots).

Figura 7. Bootstrap randomization showing families with higher, equal and fewer numbers of

useful species than expected by chance.

2

Introdução

As plantas são essenciais para a subsistência e bem-estar humanos e vem sendo

utilizadas nas florestas tropicais há milhares de anos. Na Amazônia, comunidades indígenas e

outras comunidades tradicionais têm colhido produtos vegetais de florestas desde pelo menos

13.000 anos atrás, e também cultivavam plantas em hortas e roças desde então (Roosevelt

2014). Além do uso para a subsistência (Lévi-Strauss, 1952), algumas plantas das florestas

amazônicas entraram nos mercados internacionais desde a colonização europeia (Souza, 2009).

Sabe-se que muitas espécies arbóreas que dominam as florestas oligárquicas na

Amazônia são localmente úteis (Peters et al. 1989). Além da contribuição dos fatores

ambientais (Pitman et al. 2001) e evolutivos (Dexter & Chave 2016) na formação das florestas

oligárquicas, diversos estudos ressaltam que as sociedades pré-colombianas promoveram a

formação de fragmentos de florestas modernas dominadas por uma ou algumas espécies úteis

e domesticadas (Balée 1989; Politis 2009; Levis et al. 2017; Levis et al. 2018). Entretanto, em

escala continental, a associação entre o domínio das espécies arbóreas e seus usos permanece

incerta. Aqui ressaltamos duas hipóteses que debatem essa associação.

Uma hipótese é de que a hiperdominância das espécies arbóreas na Amazônia em escala

continental pode ser um artefato da seleção humana e propagação a longo prazo dessas plantas

com características úteis e desejadas (Roosevelt 2014; ter Steege et al. 2013). A nível de

espécie, a intensidade e duração das práticas de seleção e propagação das plantas úteis podem

resultar em populações incipientes, semi ou totalmente domesticadas (Clement 1999; Levis et

al. 2017). As populações em diferentes graus de domesticação diferem quanto ao grau das

variações morfológicas e genéticas em relação às populações silvestres e também quanto à

dependência do manejo humano para suas sobrevivências e reproduções. Por outro lado, a

hipótese da disponibilidade sugere que as pessoas provavelmente usam as plantas mais

disponíveis em um ecossistema (Phillips & Gentry 1993; Albuquerque et al. 2015), por

exemplo, plantas mais próximas aos assentamentos ou com maior abundância.

Neste estudo, integramos os conhecimentos etnobotânicos e ecológicos para avaliar a

relação entre os usos das espécies arbóreas amazônicas e seus tamanhos populacionais. A forma

como as pessoas usam as espécies arbóreas são descritas para fins de subsistência ou

comerciais, correspondendo a seis categorias de uso: alimentícia, medicinal, manufatureira,

construção, cobertura de moradias ou abrigos e lenha.

3

Objetivos Objetivo geral

Avaliar a relação entre a utilidade de espécies arbóreas na Amazônia e seus tamanhos

populacionais.

Objetivos específicos

Avaliar as seguintes questões:

(i) As espécies úteis são mais abundantes que as espécies não úteis?

(ii) Como o tamanho populacional varia entre categorias de uso e graus de domesticação?

(iii) O número de espécies úteis dentro das famílias aumenta com o número total de espécies

na família?

4

Capítulo 1 Coelho, S.D., Levis, C., Baccaro, F.B., Figueiredo, F.G.O., Antunes, A.P., ter Steege, H., Peña-Claros, M., Clement, C.R., Schietti, J. Useful arboreal species dominate Amazonian forests. Manuscrito formatado para Nature plants.

5

Research Article Useful arboreal species dominate Amazonian forests Sara D. Coelho1*, Carolina Levis1,2, Fabrício B. Baccaro3, Fernando O. G. Figueiredo4, André

P. Antunes5, Hans ter Steege6,7, Marielos Peña-Claros2, Charles R. Clement8, Juliana Schietti4

1 Programa de Pós-graduação em Ecologia, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia

(INPA), Manaus, AM, Brazil 2 Forest Ecology and Forest Management Group, Wageningen University & Research

(WUR), Wageningen, The Netherlands 3 Departamento de Biologia, Universidade Federal do Amazonas, Manaus, AM, Brasil 4 Coordenação de Pesquisas em Biodiversidade, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia

(INPA), Manaus, AM, Brazil 5 Redefauna - Rede de pesquisa em diversidade, conservação e uso da fauna da Amazônia,

Estrada do Bexiga, 2584 - Bairro Fonte Boa, Tefé, AM, 69553-225, Brazil 6 Naturalis Biodiversity Center, Vondellaan 55, Postbus 9517, 2300 RA Leiden, The

Netherlands. 7 Systems Ecology, Free University Amsterdam, The Netherlands. 8 Coordenação de Tecnologia e Inovação, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia

(INPA), Manaus, AM, Brazil

Corresponding author: Sara Deambrozi Coelho ([email protected])

6

ABSTRACT

For more than 13,000 years, Amazonia’s inhabitants have been using forest plants.

Hypotheses about the association between plant abundance and their use suggest either that

plant availability influences uses or that use influences abundance of useful plants in modern

forests via long-term human activities. The relationship between usefulness of arboreal

species and their population sizes in Amazonian forests at the continental-scale is, however,

unknown. Here we show that Amazonian forests are dominated by useful arboreal species,

which include at least 2326 species. Our model predicts that hyperdominant species have at

least 80 % chance to be useful, whereas non-hyperdominants have only 9 % chance of being

useful. Incipiently domesticated species are the most abundant in Amazonian forests, whereas

domesticated species are less abundant. Our analyses elucidate the enormous usefulness of

Amazonian forests, although this usefulness seems invisible today, which may explain why

the forests have been destroyed to supply cattle and grain to world markets.

INTRODUCTION

Plants are essential for human livelihoods and welfare. In Amazonia, indigenous and other

traditional communities have harvested plant products from forest landscapes since at least

13,000 years ago, and also cultivated plants in homegardens and swiddens (Roosevelt, 2014).

Plants from Amazonian forests are mostly used for subsistence (Lévi-Strauss, 1952), but some

have entered international markets since European colonization (Souza, 2009). Many arboreal

species that dominate Amazonian forests are locally useful (Peters et al., 1989), yet at a

continental-scale, the association between the dominance of plant species and their usefulness

remains unclear.

Ter Steege et al. (2013) hypothesized that abundance of arboreal species in Amazonia at a

continental scale may be an artefact of long-term human selection and propagation of those

7

plants with useful and desired traits. Selection and propagation of useful species may result in

the domestication of plant populations and the intensity and duration of these practices can

result in incipiently domesticated, semi-domesticated, or fully domesticated populations

(Clement 1999). Incipiently and semi-domesticated populations can survive and reproduce

when abandoned by humans, whereas fully domesticated populations depend on human

management to survive and reproduce and present significant changes in morphological and

genetic variability. Studies show that pre-Columbian societies promoted the formation of

patches of modern forests dominated by one or a few useful species (Balée, 1989; Politis,

2009; Levis et al., 2017, 2018). This is added along with the environmental (Pitman et al.,

2001) and evolutionary factors (Dexter and Chave, 2016) that also contribute to the pattern of

species commonness forming the majority of individuals in plant communities, known as

oligarchy. Depending on plant use type, ancient and current human activities in forests have

been argued to enhance or to reduce plant species densities locally, and have been

hypothesized to be one of the causes of hyperdominance of useful species in Amazonia (ter

Steege, N.C.A. Pitman, et al., 2013; Roosevelt, 2014).

By contrast, the availability hypothesis suggests that people are likely to use the most

available plants in an ecosystem (Albuquerque, 2006), for example, plants closer to the

settlements or with greater abundance. Although many species used for medicine and food are

locally rare in Amazonian forests (Guèze et al., 2014), geographic range (Cámara-Leret et al.,

2017) and abundance (Byg et al. 2006; Gonçalves et al. 2016) of species have been shown to

be positively correlated with the number of useful plants at local and landscape spatial scales.

Yet, it is still unknown if these patterns occur at the scale of Amazonia.

Here, we integrated ethnobotany and ecology to assess the relationship between the

usefulness of Amazonian arboreal species and their population sizes. To evaluate the

usefulness of the Amazonian flora, we reviewed plant uses documented in the last decades

8

throughout Amazonia for subsistence or commercial purposes. We classified arboreal species

into six use categories: food, medicine, manufacturing, construction, thatching and firewood.

We then addressed the following questions: Are useful species more abundant than non-useful

species? How does population size vary among use categories and degree of domestication?

Does the number of useful species within families increase with the number of species

belonging to the family?

METHODS

We used data of 4,608 species distributed in 1,170 plots across the Amazon basin and Guiana

Shield (Amazonia) compiled by the Amazon Tree Diversity Network (ATDN) to provide a

list of useful palm and woody non-lianescent species (here defined as arboreal species) and of

their estimated population sizes (ter Steege, N.C.A. Pitman, et al., 2013). In ATDN inventory

plots, individuals with > 10 cm DBH were sampled in mainly one-hectare plot located in five

main types of lowland forests in Amazonia: terra firme, white-sand, and seasonally or

permanently flooded terrain (várzea, igapó, swamp). Our starting point was the species list

available in (ter Steege, N. C. A. Pitman, et al., 2013). We then followed two steps for data

assessment. In the first step, the taxonomic nomenclature and synonyms were verified with a

new checklist vetted by taxonomists (Cardoso et al., 2017) and available in (ter Steege et al.,

no date), reducing the number of species to 4,962 accepted species (ter Steege, N. C. A.

Pitman, et al., 2013) 4,627 were accepted. We summed the population sizes of the species

aggregated by synonymy. In the second step, other errors were also verified based on the

checklist of species from Cardoso et al. (2017): (i) we excluded the Old World and cultivated

(even if they are native) or non-native species from our analysis (10 species); (ii) for non-tree

species, we excluded lianas and vines (9 species), but maintained those classified by

taxonomists as shrubs, small shrubs, subshrubs, small trees, treelets; (iii) we also maintained

9

those species generally considered to have < 10 cm DBH (96 species) in order to retain

species and individuals sampled in the field with > 10 cm DBH. We maintained non-

Amazonian species, because many species that are considered typical of other biomes

(savannas and montane biomes) also occur in the ecotones between the Amazon biome and

non-Amazonian biomes; this situation is common across the Amazon basin, which includes

savannas and the lower parts of the Andes (Eva et al., 2005). In total, 4,608 species were

analysed in this study. The patterns of species usefulness and dominance in Amazonian

forests remained the same between our list (4608) and Cardoso et al. (2017) (3753) species

list (Supplementary Text 1).

Ter Steege et al. (2013) showed that only 227 hyperdominant tree and palm species dominate

Amazonian forests. By correcting for synonyms, 216 species remained hyperdominant

species; their population sizes vary from approximately 381 million to 5.2 billion of

individuals. Of the 85 known domesticated arboreal species, we identified 84 in our study

(Elaeis oleifera was absent), with populations considered to be incipiently, semi, or fully

domesticated (Clement, 1999; Levis et al., 2017) (hereafter, domesticated species).

Domesticated species were included in the analysis as useful species and for them we

assigned uses as any other useful species.

Literature review

We used 29 ethnobotanical studies (Supplementary Table 1 and Text 2) to identify the uses of

arboreal species in Amazonia published between 1926 and 2013 (Figure 1). Ethnobotanical

studies covered different regions and ethnic groups, including indigenous, other traditional

non-indigenous people and rural people. Despite similar plant uses may be shared among

different ethnic groups and cultures (Bennett, 1992), our analyses extrapolate geographically

localized ethnobotanical information to continental scale. We grouped subspecies or varieties

10

mentioned in the studies into the corresponding species and accepted species with “cf.”

identification as belonging to the named species. We only considered studies that adopted

botanical nomenclature with specimens identified at the species level and we excluded those

that only presented common names of the plants.

Figure 1. Location of the ethnobotanical studies of useful arboreal species in the Amazonia.

The citation of the ethnobotanical study (Supplementary Table 1) is given for each location on

the map. Ethnobotanical studies are classified in two categories of spatial coverage: local

studies (red dots) and large-scale compilations (asterisks). Black asterisks represent studies

conducted in a country, and blue asterisks represent studies in the State of Pará, Brazil, and

the Orinoco River, Venezuela. The number of asterisks represents the number of compilations

State of Para

0 200 400600 km

-80 -75 -70 -65 -60 -55 -50 -45

-20

-15

-10

-50

5

1

3

8

9

10

20

21

24

4

25

28

211

26

26

26

14

12

17

13

26

11

11

7

19

19

19

19

29

18

15

5

6 16

11

in a given country. The studies of Patiño (2002) and Revilla (2012) are not represented on the

map, since they cover the entire Amazon basin and Guiana Shield.

We classified the ethnobotanical studies in two categories of spatial coverage: local studies, in

which the authors conducted data collection with botanical inventories and interviews in one

or more communities in a specific location; and compilations, which present a dataset of plant

uses of a broad region. From the compilations, such as for the Neotropical region (Patiño,

2002) and the Amazon basin (Revilla, 2002), we included only the species from our list of

4,608 species. For the selection of the ethnobotanical studies, we followed the criteria: (i) we

preferentially included compilations; (ii) ethnobotanical studies with indigenous Amazonian

groups; (iii) ethnobotanical studies from different regions in order to cover a broad spatial

area.

All uses recorded from the literature review were classified into ethnobotanical categories

based on Prance et al. (1987) and Macía et al. (2011). Our analyses focus on fundamental

elements to supply the materials and needs of daily life reported in the literature, which

correspond to six categories of use: food, medicine, manufacturing, construction, thatching

and firewood (Supplementary Table 2). For each of the arboreal species we assigned a main

use category, which was determined by the most cited use category in the references.

Assigning a main use may help us have a more comprehensive understanding of plant uses.

We did not attribute a main use category to 31 % of the useful species, which include 18 % of

the useful hyperdominants, because they presented the same number of citations among two

or more use categories. Our final dataset includes the correct botanical name of the useful

species and their corresponding common names, all use categories mentioned for each

species, principal use category, and the references that contributed the plant use information.

12

Statistical analyses

We constructed a collector curve to assess the cumulative number of useful arboreal species

recorded during the last century in the ethnobotanical studies. Each ethnobotanical study was

used as the sampling unit.

Given the similar number of useful and non-useful species, we compared the mean population

sizes of useful and non-useful species with a one-way ANOVA with log10 transformation

before the analysis to normalize the population mean variable. We also investigated if mean

population sizes differ between useful and non-useful species among phylogenetically related

species at the genus and family level using Generalized Linear Mixed Models (GLMM) (lme

function of nlme package; Supplementary information). We adopted this analytical

framework because more closely related species may have more similar population sizes

(Dexter and Chave, 2016). To control for phylogenetic correlations of species, we defined

“genus” or “family” as random factors in the analyses. We estimated the separate

contributions of both, fixed effects (category of use) and random effects (genera or family)

calculating the marginal and conditional R2 of each model. Marginal R2 provides the variation

explained only by the fixed effect, while conditional R2 gives the variation explained by fixed

and random effects in the model (Nakagawa and Schielzeth, 2013). For all GLMM we tested

the random intercept model and the random intercept and slope model and choose those with

the lowest AIC value (Zuur et al., 2009). We repeated this framework analysis for individual

category of use and for the subset of genera that harbours domesticated species. We also build

a GLM with binomial error distribution to predict the probability of species being useful

according to their population size. We did log10 transformation before the analysis to

normalize the population mean variable.

To assess how population sizes of species differ among the six use categories (food, medicine,

manufacture, construction, thatching and firewood) we performed bootstrap for (i) species

13

used in more than one use category (called ‘multiple uses’; species is reported in more than

one use category), (ii) species may be used in more than one use category but we assigned

them a main use category (called ‘main use category’; species is reported in only one use

category), and (iii) species used in one use category (called ‘single use’; species is reported in

one use category). Bootstrap was chosen in order to account for the large differences among

sample sizes (number of species) between the use categories (Manly, 2007). We also

performed bootstrap to assess how population sizes of species differ among useful and non-

useful categories, and the degrees of domestication (incipiently, semi and fully domesticated

species). For these analyses, bootstrap was performed using the function groupwiseMean

(Rcompanion package) with a confidence interval of 95 % and 9999 randomizations.

To evaluate the relationship between the population sizes of species and the frequency of

species (number of plots where they occur) across Amazonia, we used a linear model (LM)

after log10 transformation to normalize both variables.

To assess which families have more or less useful species than expected by chance, we also

performed a bootstrap. The number of species within a family was randomized with

replacement and the mean number of useful species of each family was calculated based on

overall species pool. We then subtracted the observed number of useful species from the

bootstrapped mean. When differences equal zero, the number of useful species are similar to

number of useful species expected by chance. The 95% confidence interval of the difference

were based on 9999 randomizations. All analyses were performed in the R environment (R

Development Core Team 2017).

Data availability

List of uses of arboreal species from 29 ethnobotanical studies will be available on Dryad.

The botanical name of the useful species, common names, use categories of the species,

14

principal use category and the references from the literature review are present in this list. Use

categories: Food, Medicine, Manufacturing, Construction, Thatching and Firewood.

RESULTS

We found that fifty percent of the arboreal species in the ATDN inventory (2,326 out 4,608)

are useful in Amazonia, according to the 29 ethnobotanical studies consulted in this study. We

also found that the number of useful arboreal species in Amazonian forests is probably higher

than we report in this study (Figure 2a) as the collector curve did not stabilized. The useful

species are distributed in 571 of the 738 genera (77 %) and 102 of the 115 families (89 %). Of

the 2,326 useful species, 1,579 species are used for construction (68 %), 1,043 for food (45

%), 1,052 for their medicinal properties (45 %), 894 to manufacture things (38 %), 302 for

firewood (13 %) and 46 for thatching (2 %). The sum of these percentages exceeds 100 %

because 1,395 species (60 %) have multiple uses (i.e., they are included in more than one use

category). On the other hand, 931 species (40 %) are restricted to a single use category: 437

species (19 %) are only used for construction, 208 (9 %) for food, 197 (8.5 %) for medicinal

properties, 77 (3 %) for manufacturing, 12 (0.5 %) for firewood. No species has their use

restricted to thatching.

15

Figure 2. (a) Cumulative number of useful woody species documented in Amazonia, based on

29 ethnobotanical studies during the period 1926-2013; (b) Species accumulation curve

showing the 29 studies ordered by contribution of new species (black dots) and the total

number of useful species that each study contributed to the dataset (red dots for local studies

and black asterisks for compilations). The highest asterisks values correspond to Corrêa

(1926), Revilla (2002) and la Torre et al. (2008), carried out in Brazil, Ecuador and all of

Amazonia, respectively.

Useful species had together a median population size of approximately 34 million individuals,

5.65 times higher than non-useful species (p < 0.01, F = 189.7; Figure 3). The majority of

hyperdominant species (194 out 216 species; 90 %) are useful.

1920 1940 1960 1980 2000

0

500

1000

1500

2000

2500

Year of publication

Num

ber o

f spe

cies

a

0 5 10 15 20 25 30

0

500

1000

1500

2000

2500

Number of bibliographies

b

16

Figure 3. Relationship between the mean population sizes of useful and non-useful arboreal

species in Amazonia. Small black lines represent the species. Large black lines represent the

median. Grey shadow represents the density of species distributed throughout the population

size.

The linear mixed effect model that compared the differences in population size between

closely related useful and non-useful species revealed that useful species are more abundant

than non-useful species within all genera (p < 0.01; conditional R2 = 0.34) and families (p <

0.01; conditional R2 = 0.24) (Supplementary Figure 1a and c). In the model using genera, use

accounted for 12 % of the variation of population size (marginal R2 = 0.12), while use and

genus together explained 34 % (conditional R2 = 0.34; β = 0.60). When we analysed only

genera containing domesticated species, use accounted for 18 % of the variance (marginal R2

= 0.18), while use and genus together explained 32 % (conditional R2 = 0.32; β = 0.71)

(Supplementary Figure 1d and Table 3). A large number of genera, 279 out of 738 (27 %) are

monospecific, 153 of them had only useful species and 126 had only non-useful species

(Supplementary Figure 1b and Table 3). All genera that have multiple species (459 out of 738

genera) had both useful and non-useful species. The same pattern between useful and non-

Not useful Useful

Mea

n po

pula

tion

size

104

105

106

107

108

109

1010

17

useful species was found when the analysis was done per use category within genera: food (p

< 0.01; conditional R2 = 0.35), medicine (p < 0.01; conditional R2 = 0.35), manufacturing (p <

0.01; conditional R2 = 0.34), construction (p < 0.01; conditional R2 = 0.34), thatching (p <

0.01; conditional R2 = 0.34) and firewood (p < 0.01; conditional R2 = 0.34) (Supplementary

Figure 2).

We used the logistic regression model to estimate the probabilities of species being useful

according to their population sizes (Figure 4). Our model predicted that the probability of

non-hyperdominant species to be useful ranges from 9.3 % (for the species with the smallest

population size) to approximately 80 % and that the probability of hyperdominant species to

be useful ranges from 80 % (for those species with approximately 381 million individuals) to

92 % (for the most hyperdominant; e.g., Euterpe precatoria) (Figure 4a).

Figure 4. Population sizes of useful (orange circles) and non-useful (black circles) arboreal

species. Dashed lines separate hyperdominants and non-hyperdominant species according to

ter Steege et al. (2013). (a) Logistic regression that shows the probability of species being

useful according to their population size (black line); (b) Species abundance rank.

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

Population size

Prob

abilit

y of

use

105 106 107 108 109

a

0 1000 2000 3000 4000 5000

Species abundance rank

Popu

latio

n si

ze

b

105

106

107

108

109

18

Useful species in any use category exhibited higher population mean sizes than non-useful

species for both the main use category (SI Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 4) and the

multiplicity of uses (Figure 5 and Supplementary Table 4). For species with multiple uses,

population size of thatching species is the highest among the use categories, and only includes

the Arecaceae (20 genera) and Lecythidaceae (Couratari guianensis) families; all thatching

species have multiple uses. The firewood category had mean population sizes greater than the

food and construction categories, and the mean population sizes did not vary among the other

use categories. Looking at the main use category, mean population size of food is higher than

medicine and the mean population sizes do not vary among the other use categories. Mean

population size of the single use categories are smaller than species with a multiplicity of

uses, for all use categories (Supplementary Table 4).

Figure 5. Relationship between the mean population sizes of arboreal species and their use

categories. Bootstraps show means and confidence intervals of population sizes of species

based on their single use (green) and multiple uses (black). Single use: species is used in one

Food Medicine Manufacture Construction Thatching Firewood No use

Use categories

Popu

latio

n si

ze

105

106

107

108

109

19

use category and it is reported in one use category. Multiple uses: species is used in more than

one use category and it is reported in more than one use category. The bars represent 95 %

confidence intervals.

Mean population sizes varied among non-useful, useful non-domesticated and domesticated

species (Figure 6 and Supplementary Table 5). Incipiently domesticated species had higher

mean population sizes than other domesticated species and non-domesticated useful species

(Figure 6a). Fully domesticated and non-useful species have the smallest population sizes in

Amazonian forests (see Supplementary Text 3 for domesticated hyperdominant species). As

expected, our analysis showed a relationship between population size and frequency of

species in the landscape, for all species (p < 0.01; R2 = 0.74; b = 0.67, Figure 6b), and for

each one of the categories: non-useful (p < 0.01; R2 = 0.60; b = 0.57); useful non-

domesticated (p < 0.01; R2= 0.78; b = 0.70); incipiently domesticated (p < 0.01; R2= 0.71; b =

0.68); semi-domesticated (p < 0.01; R2= 0.90; b = 0.80) and fully domesticated (p < 0.01; R2=

0.87; b = 0.82).

NU UND I S F

Use categories and domestication degree

Popu

latio

n si

ze

a

105

106

107

108

109

1 2 5 10 20 50 100 200 500

Number of plots

b

105

106

107

108

109

20

Figure 6. Mean population sizes of species among different scenarios of species’ usefulness

and degree of domestication: non-useful (NU; dark grey), useful non-domesticated (UND;

light grey), and incipiently (I; red), semi (S; blue) and fully (F; yellow) domesticated species.

Dashed lines separate hyperdominants and not hyperdominant species. (a) Mean population

sizes among the use categories and degree of domestication; (b) Relationship between

population mean size and their frequency in the landscape (number of plots). The bars

represent 95 % confidence intervals.

Some families stand out as being more or less useful than predicted by the model based on the

total number of species within families (Figure 7). Moraceae, Arecaceae, Meliaceae,

Myristicaceae, Apocynaceae, Urticaceae, Burseraceae, Euphorbiaceae, Bixaceae and

Rosaceae have more useful species than expected by chance; whereas Rubiaceae,

Chrysobalanaceae, Myrtaceae, Ochnaceae, Sapindaceae, Ebenaceae, Nyctaginaceae,

Pentaphylacaceae and Linaceae have fewer useful species than expected by chance.

21

Figure 7. Bootstrap randomization showing families with higher (orange lines), equal (blue

lines) and fewer (black lines) numbers of useful species than expected by chance. Lines

represent variation in number of useful species within families. Values indicate difference in

number of species observed and expected. Negative values indicate low usefulness. Positive

values indicate high usefulness.

RubiaceaeMyrtaceae

ChrysobalanaceaeOchnaceae

SapindaceaeMelastomataceae

AnnonaceaeEbenaceae

NyctaginaceaeVochysiaceae

MalpighiaceaePentaphylacaceae

PrimulaceaeAquifoliaceaeCapparaceae

LinaceaeLauraceae

ErythroxylaceaeSapotaceaeStyracaceae

OlacaceaeAchariaceae

ViolaceaeHypericaceae

AraliaceaeIxonanthaceae

RutaceaeCalophyllaceae

CelastraceaeMagnoliaceae

ThymelaeaceaeEuphroniaceaeSchoepfiaceae

RhizophoraceaeElaeocarpaceae

ProteaceaeLacistemataceaePicrodendraceae

PutranjivaceaeMonimiaceae

DipterocarpaceaeBonnetiaceae

OleaceaeVerbenaceae

CyrillaceaeBuxaceae

LepidobotryaceaePolygalaceae

CardiopteridaceaeCanellaceae

PodocarpaceaeFabaceae

PolygonaceaeLoganiaceae

PhyllanthaceaeSabiaceae

SymplocaceaeAnisophylleaceae

PhytolaccaceaeAsteraceaeOpiliaceae

HernandiaceaeRhabdodendraceae

PiperaceaeConnaraceaeBoraginaceaeTapisciaceae

StemonuraceaeTheaceae

AdoxaceaeSantalaceaeIcacinaceae

AchatocarpaceaeHydrangeaceae

AcanthaceaeDilleniaceae

MettenusiaceaeCactaceae

PeridiscaceaeGoupiaceaeZamiaceae

XimeniaceaeLamiaceae

PicramniaceaeLythraceaeUlmaceae

CaricaceaeLecythidaceae

SimaroubaceaeCannabaceaeRhamnaceaeHumiriaceae

DichapetalaceaeBixaceae

RosaceaeMetteniusaceae

ClusiaceaeSiparunaceae

CombretaceaeMenispermaceae

AnacardiaceaeSolanaceaeSalicaceae

CaryocaraceaeEuphorbiaceae

BignoniaceaeBurseraceae

MalvaceaeUrticaceae

ApocynaceaeMyristicaceae

MeliaceaeArecaceaeMoraceae

−50 −25 0 25Variation in number of useful species

Fam

ilies

22

DISCUSSION

Our review of the ethnobotanical literature combined with population estimates of arboreal

species showed that Amazonian forests are highly dominated by useful species. Median

population size of useful species is higher than that of non-useful species, both in terms of

number of individuals and species number as useful species represent more than 50 % of the

arboreal species assessed. This pattern of species abundance also holds true within genera and

families of species expected to have similar evolutionary histories and abundance (Dexter &

Chave 2016). Our findings illustrate the pronounced usefulness of Amazonian forests and that

useful arboreal species represent most of the hyperdominant species. Our results reveal that

the pattern of oligarchic forests dominated by useful species, found at local and landscape

scale in Amazonia (Balée 1989; Peters et al. 1989; Levis et al. 2018) and Mesoamerica

(Campbell et al., 2006), also occur at the scale of Amazonia. Our analyses also reinforce the

findings of Levis et al. (2017) and find that high population size is not related only to

domesticated species but expand it to hundreds of useful species differing in their use

category. Nevertheless, the causes of arboreal species abundance in Amazonia are still

debated.

Contentious debates remain over the influence of long-term human activities on plant

abundance in Amazonian forests (Bush and McMichael, 2016; Levis et al., 2017). Our

findings agree with both hypotheses that plant availability influences use and human practices

influences plant abundance yet strengthens the role of plant availability on their utility at

continental scale, supporting patterns found at local and landscape scales (Byg, Vormisto and

Balslev, 2006; Gonçalves, Albuquerque and de Medeiros, 2016).

The remaining non-useful species suggests that we did not find uses for those species or that

they are in fact non-useful, maybe due to undesirable traits. Useful species with low

population sizes may have very desirable uses and characteristics associated with plant

23

morphology or physical and chemical proprieties, such as wood density, fruit size (Pedrosa,

Clement and Schietti, 2018) and medicinal properties (Saslis-Lagoudakis et al., 2012) that

make them more useful to people.

We found that mean population size of species does not differ among the use categories but

differ for the use category firewood that presented the highest mean population size when we

look at the species with multiple uses. A question raised from our findings is why even the

construction and firewood use categories, in which the removal of individuals is more

frequent than in other use categories especially for commercial purposes, are equal or more

abundant than other use categories and more abundant than non-useful species. This is

consistent with the findings of previous local studies, which argue that the most widespread

species are preferentially used by people for construction and thatching (Cámara-Leret et al.

2017) and that abundance influences the use of species for construction, materials and

firewood (Byg et al. 2006; Guèze et al. 2014; Gonçalves et al. 2017). However, we did not

analyse the distance of useful plant occurrence from current settlements or archaeological

sites neither the plant abundances on and around those sites. It has been hypothesized that

species used for construction and crafting are more easily substituted by people. Their

physical properties, such as mechanical resistance or durability, are likely to be shared by

many species (Guèze et al. 2014), although there are preferences for species (Walters, 2005)

and a limited number of alternative species that could be used as substitutes (Brown et al.,

2011). This may also explain the high number of species within the construction use category,

followed by food and medicine. These findings support that people use plants because they

are easier to gather (more available).

Although plant availability explains arboreal species use among all use categories, other

findings challenge it. Species with multiple uses have larger mean population sizes than

species that have a single use category. High abundance and wide distribution of species on

24

the landscape increase people-plants interactions and the probability and diversity of plant

uses (Prance et al., 1987; Hastorf, 2006). By contrast, a greater number of uses may have

favoured plant dispersal and abundance through management practices (Peters et al. 2000;

Levis et al. 2018). Intentional or non-intentional management by ancient and contemporary

human societies has created a mosaic of landscape with dominant plant populations through

enrichment of useful species by practices such as removal of non-useful plants, protection and

human transportation of useful plants (Levis et al., 2018). This suggests that not only plant

availability but also long-term management may contribute to the patterns of population sizes

of useful species among the use categories.

Furthermore, we found that domesticated species vary in their population size and that

incipiently domesticated species have the highest population size. Previous study have

provided knowledge that the majority of the hyperdominant and domesticated species have

incipient domesticated populations (Levis et al., 2017). We also compared the population size

of species with populations categorized into different degree of domestication (Clement 1999)

and of non-useful and useful non-domesticated species. On the other hand, species with fully

domesticated populations are the lowest in population size, as well as non-useful species are.

However, species that have fully domesticated populations are rare in old-growth forests

organized by the ATDN, but expected to be abundant in homegardens, swiddens and

secondary forests closer to human settlements, supposing even higher abundance of useful

species than found in this study. Additionally, we observed a strong relationship between the

abundance and frequency of species on the landscape, and that this relationship is more

pronounced for domesticated species, followed by useful non-domesticated and non-useful

species. This suggests that although people often use species that are very abundant and

widespread on the landscape, they also select and propagate species with low population sizes

but very useful. We hypothesize that the pattern of choice of plants by people may also reflect

25

the selection of phylogenetically close plants because of a given similar desired trait or the

plants are randomly chosen.

Among families, there are families with more or less useful species than expected by chance,

revealing selectivity of certain families. The choice for family use may be due to the

similarities of useful properties of closely related species linked to some types of uses

(Phillips et al., 1994). For instance, few families were used more than predicted by chance

alone because of their interesting characteristics such as properties for construction as shown

in Peruvian Amazonia (Phillips & Gentry 1993 I). At the genus level, traditional medicinal

plants are not randomly chosen for uses. The plants chosen by cross-cultural people accessing

different floristic composition were concentrated in specific parts of phylogenetic trees

according to the specific medicinal uses (Saslis-Lagoudakis et al., 2012). There is evidence

that all highly useful families we found (Moraceae, Arecaceae, Apocynaceae, Meliaceae,

Myristicaceae, Burseraceae, Bixaceae, Euphorbiaceae and Rosaceae; Fig. 7) have been used

since pre-Columbian times (Roosevelt, 2013; Watling, Mayle and Schaan, 2018) dating up to

13,000 years ago for Arecaceae, which is commonly found in archaeological sites. All those

highly useful families have multiple uses. We found uses in five out the six use categories,

with the exception of thatching, whereas Arecaceae have uses in all use categories. In modern

forests, those highly useful families were found to be very abundant, accounting together for

33 % of the hyperdominant species. Additional local studies reinforce the effects of ancient

human activities on modern dominance of useful plants. For instance, phytolith assemblages

of palm and other useful species in archaeological sites of southwertern Amazonia, were

correlated with an overall increase in human land use (McMichael et al., 2015; Watling et al.,

2017). On the other hand, some families have less useful species than expected by chance.

They do not account for hyperdominant species, except Chrysobalanaceae, a family less

useful than expected by chance and with many hyperdominant species (12 species). This

26

support the idea that dominance is not a cause for plant uses in all cases or we did not find

uses for all its useful species. Also, all those little useful families have multiple uses, but in a

less extent than those highly useful families. We found uses ranging from three to five use

categories of the total of six. By these findings, we argue that humans respond to the

ecological process of plant availability, yet additional evidences reinforce the effects of

ancient human activities on modern dominance of useful plants.

Considering the recent historical context of plant resource uses in Amazonian forests is also

important. Tree species more intensively exploited since the beginning of the 20th century to

supply both national and international markets with timber such as Aniba rosiodora,

Swietenia macrophylla and Cedrela spp. (Silva, 1995) show that their population sizes have

been decreasing in recent decades and are threatened nowadays (IUCN, 2018). Even regions

farthest from the settlements – mostly located across the rivers – have been accessed by

humans and exploited for contemporary commercial purposes. Drastically, the accessibility of

the once remote refuge areas has increased with the ongoing Amazonian deforestation and

can lead to the vulnerability or to extinction of at least 36% and up to 57% of all Amazonian

arboreal species in the next decades (ter Steege et al., 2015).

The rapid increase in Amazonian deforestation in recent years threatens the forest usefulness,

crucial for traditional indigenous and non-indigenous livelihoods and of potential economic

value to the market. The hyper usefulness of arboreal species and the wide local and

traditional knowledge accumulated throughout generations – recorded by ethnobotanists over

years – highly contrast to the so-called useless forest as a barrier to the economy

development, claimed by conservative politicians and agribusiness lobby representatives.

Instead, Amazonian forests are neither economically recognized nor sustainably managed.

Highly usefulness value of Amazonian forests seems to be invisible. Neglecting the current

potential usefulness of the Amazonian forests in provisioning resources for subsistence and

27

economy bases have been highly misleading forests sustainability and threatening the richness

tropical forest in the world. Food resources, here represented by 1,043 arboreal species,

supply subsistence opportunities to millions of people living in Amazonian forests today and

even extends to the international market, e.g., Brazil nut (Bertholletia excelsa) (Shepard and

Ramirez, 2011) and açaí (Euterpe oleracea and E. precatoria) (Paniagua-Zambrana,

Bussmann and Macía, 2017). Medicinal plants, here represented by 1,052 arboreal species in

mature forests, are not widely used in pharmaceutical research and even less so in markets.

They could be developed in new drugs and other bioindustrial opportunities (Nobre et al.,

2016), under traditional knowledge rights. Instead, they are threatened by deforestation and

degradation (Shanley and Luz, 2003). Estimated to be worth billions of dollars on

international markets, part of the timber value has been obtained by illegal logging and

deforestation (Clement and Higuchi, 2006). Subsistence and commercial community-based

management programs based on interdisciplinarity and science-led conservation governance

are a strong window of opportunity to the sustainable use of Amazonian natural resources

face to the rough deforestation.

Our study has shown the enormous usefulness of Amazonian forests and that useful arboreal

species dominate Amazonia at a continental scale. Our findings highlight the role of plant

abundance and frequency in increasing the probability of plant uses in Amazonia, which is

associated with the density and distribution of plant populations on the landscape.

Considering the immense usefulness of the Amazonian arboreal flora and their socioeconomic

importance, deforestation in these forests is directly affecting the provisioning of resources

for the livelihoods of Amazonian forests dwellers and reducing the availability of plant

models with socioeconomic potential.

28

REFERENCES

Albuquerque, U. P. (2006) ‘Re-examining hypotheses concerning the use and knowledge of

medicinal plants: a study in the Caatinga vegetation of NE Brazil.’, Journal of ethnobiology

and ethnomedicine, 2, p. 30. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-2-30.

Balée, W. (1989) ‘The Culture of Amazonian Forests’, in Posey, D. A. and Balée, W. (eds)

Resource Management in Amazonia: Indigenous and Folk Strategies. Bronx, New York,

USA: The New York Botanical Garden, pp. 1–21.

Bennett, B. C. (1992) ‘Plants and People of the Amazonian Rainforests: the role of

Ethnobotany in Sustainable Development’, BioScience, 42(8), pp. 599–608. doi:

10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004.

Brown, K. A. et al. (2011) ‘Assessing natural resource use by forest-reliant communities in

madagascar using functional diversity and functional redundancy metrics’, PLoS ONE, 6(9).

doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024107.

Bush, M. B. and McMichael, C. N. H. (2016) ‘Holocene variability of an Amazonian

hyperdominant’, Journal of Ecology, 104(5), pp. 1370–1378. doi: 10.1111/1365-2745.12600.

Byg, A., Vormisto, J. and Balslev, H. (2006) ‘Using the useful: Characteristics of used palms

in south-eastern Ecuador’, Environment, Development and Sustainability, 8(4), pp. 495–506.

doi: 10.1007/s10668-006-9051-6.

Cámara-Leret, R. et al. (2017) ‘Fundamental species traits explain provisioning services of

tropical American palms’, Nature Plants. Nature Publishing Group, 3(January), pp. 1–7. doi:

10.1038/nplants.2016.220.

Campbell, D. G. et al. (2006) ‘The feral forests of the Eastern Petén’, in Balée, W. and

Erickson, L. C. (eds) Time and Complexity in Historical Ecology: Studies in the Neotropical

Lowlands. Columbia University Press.

Cardoso, D. et al. (2017) ‘Amazon plant diversity revealed by a taxonomically verified

29

species list’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(40), p. 201706756. doi:

10.1073/pnas.1706756114.

Clement, C. R. (1999) ‘1492 and the loss of amazonian crop genetic resources. I. The

Relation Between Domestication and Human Population Decline’, Economic Botany, 53(2),

pp. 188–202. doi: 10.1007/bf02866498.

Clement, C. R. and Higuchi, N. (2006) ‘A Floresta Amazônica e o Futuro do Brasil’, Ciência

e Cultura, 58(3), p. 6.

Dexter, K. and Chave, J. (2016) ‘Evolutionary patterns of range size , abundance and species

richness in Amazonian trees’, (May), pp. 1–14. doi: 10.7717/peerj.2402.

Eva, H. et al. (2005) A proposal for defining the geographical boundaries of Amazonia, A

proposal for defining the geographical boundaries of Amazonia. doi: ISBN 9279000128.

Gonçalves, P. H. S., Albuquerque, U. P. and de Medeiros, P. M. (2016) ‘The most commonly

available woody plant species are the most useful for human populations: A meta-analysis’,

Ecological Applications. doi: 10.1002/eap.1364.

Guèze, M. et al. (2014) ‘Are ecologically important tree species the most useful? A case study

from indigenous people in the Bolivian Amazon.’, Economic botany, 68(1), pp. 1–15. doi:

10.1007/s12231-014-9257-8.

Hastorf, C. A. (2006) ‘Domesticated food and society in early Coastal Peru’, in Balée, W. and

Erickson, C. L. (eds) Time and Complexity in Historical Ecology: Studies in the Neotropical

Lowlands. Columbia University Press.

IUCN (2018) The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2018-1.

Lévi-Strauss, C. (1952) ‘The use of wild plants in tropical South America’, Economic Botany,

6(3), pp. 252–270. doi: 10.1007/BF02985068.

Levis, C. et al. (2017) ‘Persistent effects of pre-Columbian plant domestication on

Amazonian forest composition’, Science, 355(6328), pp. 925–931. doi:

30

10.1126/science.aal0157.

Levis, C. et al. (2018) ‘How People Domesticated Amazonian Forests’, Frontiers in Ecology

and Evolution, 5(January). doi: 10.3389/fevo.2017.00171.

Macía, M. J. et al. (2011) ‘Palm Uses in Northwestern South America: A Quantitative

Review’, Botanical Review, 77(4), pp. 462–570. doi: 10.1007/s12229-011-9086-8.

Manly, B. F. J. (2007) Randomization, Bootstrap and Monte Carlo Methods in Biology.

Third. Chapman & Hall/CRC.

McMichael, C. H. et al. (2015) ‘Phytolith Assemblages Along a Gradient of Ancient Human

Disturbance in Western Amazonia’, Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 3(December), pp. 1–

15. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2015.00141.

Nakagawa, S. and Schielzeth, H. (2013) ‘A general and simple method for obtaining R2 from

generalized linear mixed-effects models’, Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 4(2), pp. 133–

142. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-210x.2012.00261.x.

Nobre, C. A. et al. (2016) ‘Land-use and climate change risks in the Amazon and the need of

a novel sustainable development paradigm’, Proceedings of the National Academy of

Sciences, 113(39), pp. 10759–10768. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1605516113.

Paniagua-Zambrana, N., Bussmann, R. W. and Macía, M. J. (2017) ‘The socioeconomic

context of the use of Euterpe precatoria Mart. and E. oleracea Mart. in Bolivia and Peru’,

Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine,

13(1), pp. 1–17. doi: 10.1186/s13002-017-0160-0.

Patiño, V. M. (2002) ‘Historia y dispersión de los frutales nativos del neotrópico’. CIAT, p.

655.

Pedrosa, H. C., Clement, C. R. and Schietti, J. (2018) ‘The Domestication of the Amazon

Tree Grape (Pourouma cecropiifolia) Under an Ecological Lens’, Frontiers in Plant Science,

9(March), pp. 1–14. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00203.

31

Peters, C. M. et al. (1989) ‘Oligarchic Forests of Economic Plants in Amazonia: Utilization

and Conservation of an Important Tropical Resource’, Conserv. Biol., 3(4), pp. 341–349.

Phillips, O. et al. (1994) ‘Quantitative Ethnobotany and Amazonian Conservation’,

Conservation Biology, 8(1), pp. 225–248. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1739.1994.08010225.x.

Pitman, N. C. A. et al. (2001) ‘Dominance and distribution of tree species in upper

Amazonian terra firme forests’, Ecology, 82(8), pp. 2101–2117. doi: 10.1890/03-8024.

Politis, G. G. (2009) Nukak: Ethnoarchaeology of an Amazonian People, Current

Anthropology. doi: 10.1086/592439.

Prance, G. T. et al. (1987) ‘Quantitative ethhnobotany and the case for conservation in

Amazonia.’, Conservation Biology, 1(4), pp. 296–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-

1739.1987.tb00050.x.

Revilla, J. (2002) Plantas úteis da bacia Amazônica 2vol. Manaus: Instituto Nacional de

Pesquisas da Amazônia/SEBRAE-AM.

Roosevelt, A. C. (2013) ‘The Amazon and the Anthropocene: 13,000 years of human

influence in a tropical rainforest’, Anthropocene. Elsevier B.V., 4, pp. 69–87. doi:

10.1016/j.ancene.2014.05.001.

Roosevelt, A. C. (2014) ‘The Amazon and the Anthropocene: 13,000 years of human

influence in a tropical rainforest’, Anthropocene. Elsevier B.V., 4, pp. 69–87. doi:

10.1016/j.ancene.2014.05.001.

Saslis-Lagoudakis, C. H. et al. (2012) ‘Phylogenies reveal predictive power of traditional

medicine in bioprospecting’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(39), pp.

15835–15840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202242109.

Shanley, P. and Luz, L. (2003) ‘The Impacts of Forest Degradation on Medicinal Plant Use

and Implications for Health Care in Eastern Amazonia’, BioScience, 53(6), p. 573. doi:

10.1641/0006-3568(2003)053[0573:TIOFDO]2.0.CO;2.

32

Shepard, G. and Ramirez, H. (2011) ‘“Made in Brazil”: Human Dispersal of the Brazil Nut

(Bertholletia excelsa, Lecythidaceae) in Ancient Amazonia’, Economic Botany, 65(1), pp. 44–

65. doi: 10.1007/s12231-011-9151-6.

Silva, J. L. (1995) Amazonas - Aspectos sócio-econômicos (1930 - 1939). Edited by M. M.

Neto and C. A. M. Castro.

Souza, M. (2009) História da Amazônia. Edited by I. Maciel. Manaus: Valer.

ter Steege, H., Pitman, N. C. A., et al. (2013) ‘Hyperdominance in the Amazonian tree flora.’,

Science, 342(6156), p. 1243092. doi: 10.1126/science.1243092.

ter Steege, H., Pitman, N. C. A., et al. (2013) ‘Hyperdominance in the Amazonian Tree

Flora’, Science, 342(6156), pp. 1243092–1243092. doi: 10.1126/science.1243092.

ter Steege, H. et al. (2015) ‘Estimating the global conservation status of more than 15 , 000

Amazonian tree species’, Science, (November), pp. 9–11. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1500936.

ter Steege, H. et al. (no date) ‘Towards a dynamic list of Amazonian tree species’, PNAS, in

revisio.

Walters, B. B. (2005) ‘Patterns of Local Wood use and Cutting of Philippine Mangrove

Forests’, Economic Botany, 59(1), pp. 66–76. doi: 10.1663/0013-

0001(2005)059[0066:POLWUA]2.0.CO;2.

Watling, J. et al. (2017) ‘Impact of pre-Columbian “geoglyph” builders on Amazonian

forests’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(8), pp. 1868–1873. doi:

10.1073/pnas.1614359114.

Watling, J., Mayle, F. E. and Schaan, D. (2018) ‘Historical ecology, human niche

construction and landscape in pre-Columbian Amazonia: A case study of the geoglyph

builders of Acre, Brazil’, Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. Elsevier, 50(December

2017), pp. 128–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jaa.2018.05.001.

Zuur, A. F. et al. (2009) Mixed Effects Models and Extensions in Ecology with R. Springer.

33

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Caetano Borges Franco, who assisted with map elaboration, William E. Magnusson

and Bernardo M. Flores for discussion of early results of the work, and Rosineide Machado for

organizing information of species use. S.D.C. and C.L. thanks CNPq for a master and doctoral

scholarship.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

SI Text 1

Adjusting synonymy of the names to Cardoso et al. (2017), 52% (2146 out 4150) of species

are useful. The useful species are distributed in 540 out of 685 (79%) genus and 101 out of

113 (89%) families. Of the total of 2145 useful species, 1467 species (68%) are used for

construction, 978 (46%) are food, 965 species (45%) are medicinal, 822 (38%) are used as

manufactures, 279 (13%) are used as firewood and 45 (2%) are used as thatching. Mean

population size of useful species are higher than non-useful species.

As in our main analysis, the linear mixed effect model showed that useful species are more

dominant than non-useful species within all genera (p < 0.01; r2 = 0.36) and families (p <

0.01; r2 = 0.26) and that differences on population sizes between useful and non-useful

species are explained by both factors use and genera that account for 12% and 24% of

influence, respectively. Here when we analyse only genera of domesticated species, the

influence of use factor on the variation of population size is higher than in the general

prediction, accounting 20% for use and 14% for genera.

Logistic Regression model that predict the probability of species to be useful and the

bootstrap of population mean size among the use categories showed here the same results as

in our main analysis. Mean population size changed among non-useful, useful non-

34

domesticated and domesticated species, as in our main analysis. Incipiently and semi

domesticated species had the highest mean population size in Amazonian forests, whereas

fully domesticated species and non-useful species had the smallest mean population size.

The relationship between population size and frequency of species on the landscape did not

significantly change from our main analysis, in general (p < 0.01; r2 = 0.75; b = 0.68) and for

each one of the categories useful non-domesticated (p < 0.01; r2= 0.79; b = 0.70), incipient (p

< 0.01; r2= 0.72; b = 0.68), semi (p < 0.01; r2= 0.90; b = 0.81) and full (p < 0.01; r2= 0.89; b =

0.82) domestication degree and non-useful (p < 0.01; r2= 0.60; b = 0.57) species. The

frequency and the number of individuals of incipiently domesticated species were higher than

of the other domesticated species. Smaller frequency of species on the landscape was found

for fully domesticated species.

Some families stand out as being more or less useful than predicted by the model based on the

total number of species within families. The families with more, equal or less number of

species used than predicted by their total number of species are the same as in our main

analysis.

SI Text 2. Information about the authors of the large-scale studies compiled.

Cárdenas-López, D., Canchala, N. & Arboleda, N. Plantas alimenticias no

convencionales en Amazonia colombiana y anotaciones sobre otras plantas alimenticias.

(2013)

Dairon Cárdenas-López is a biologist and botanist. He was a coordinator of the research

program in Ecosystems and Natural Resources of the Amazon Scientific Research Institute -

Sinchi and director of the Colombian Amazonian herbarium COAH. He dedicated more than

20 years to floristic studies of Amazonia, useful plants, threatened plants, introduced plants,

zoning and forest management documented about 45,000 botanical samples collected, which

35

support the information recorded in various scientific articles, books and chapters of books

(Congresso Colombiano de Restauração Ecológica 2018).

Cavalcante, P. B. Frutas comestíveis da Amazônia. (Museu Paraense Emilio Goeldi,

2010)

Paulo Bezerra Cavalcante was an important Brazilian botanist in the history of the Amazonian

botany concentrating his studies on the plant Taxonomy. He worked on the reorganization of

the herbarium and the botanical sector of the Emilio Goeldi Museum, Pará, Brazil. He

participated in numerous scientific expeditions and floristic surveys in Pará, Amazonas and

Amapá. Cavalcante developed an extensive collection and study of several plant Amazonian

species, genera and families (Secco 2006). The book Frutas Comestíveis da Amazônia

presents fruits, showing the popular names, botanical family, scientific name and synonyms

of the plants.

Corrêa, P. Dicionário das plantas úteis do Brasil e das exóticas cultivadas 6v. (Ministério

da Agricultura, 1926)

Manoel Pio Corrêa was a Portuguese naturalist, botanist, geologist and researcher. He

dedicated to the study of applied botany, emphasizing scientific, economic and industrial

aspects of plants. He travelled the world as a researcher at the Museum of Natural History in

Paris looking for unknown plants. The works developed him gave rise to important

publications, among which are the six volumes of the Dictionary of Useful Plants of Brazil

and of Exotic Cultivated, published since 1926 (Monumentos do Rio).

Le Cointe, P. O Estado do Pará: a terra, a água e o ar. (Companhia Editora Nacional,

1945)

36

Paul Georges Aimé Le Cointe was a French-born naturalist who comes to Belém through the

French Mission. He became a chemist and geographer who studied natural products from

Amazonian flora. Le Cointe published many bibliographies since the beginning of 1900 years

about natural resources and their uses in the Amazon. He writes mainly on geography and

economy of the Amazon, publishing brochures for the government of Pará technical materials

on cacao, rubber and other topics, such as oilseeds, balsams, resins, rubbers, jutes and balatas

and woods from the Amazon rainforest (Meirelles Filho 2009). The book O Estado do Pará:

a terra, a água e o ar covers the entire physical geography of the state of Pará, with particular

emphasis on botany, and relations of shrubs and herbaceous plants to their applications in

industry, food and therapy. It also describes the orography, rivers, climate, animals, forests,

woods and minerals of Pará (Brasiliana Eletrônica 2018).

Loureiro, A. A., Silva, M. F. & Alencar, J. da C. Essências madeireiras da Amazônia 2v.

(INPA, 1979)

Arthur A. Loureiro is a researcher, forestry engineer and organizer of the Wood Collection at

National Institute of Amazonian Research (INPA). His work contains technological

information of several forest species of Amazonia. For each species described, the general

characteristics of wood, macroscopic description, uses, general information, physical and

mechanical properties are described, as well as a glossary of the main terms used in the

botanical and anatomical descriptions of the species.

Lowie, R. H. in Handbook of South American Indians v3 (ed. Steward, J. H.)

(Government Printing Office, 1948)

Robert Harry Lowie was an anthropologist, mainly interested in ethnological theory. He

published a large number of volumes. Lowie’s interst in primitive peoples expanded in scope

37

through voluminous reading and his bibliography contains some 200 books reviews. His

knowledge of South American Indians was stimulated by 1920’s. Lowie translated to English

Curt Nimuendajú’s manuscripts about some of the least known tribes in eastern Brail, the Ge-

speaking Indians, Nimuendajú’s has visited. His interest in the general area became a lasting

one, such that he was a major contributor to, and editor of, the Tropical Forest volume of the

Handbook of South American Indians (Steward 1974).

Macía, M. J. et al. Palm Uses in Northwestern South America: A Quantitative Review.

Bot. Rev. 77, 462–570 (2011)

Manuel Macía is a tropical botanist with field experience in northwestern South America,

particularly in the western Amazon. His research focuses on understanding the patterns,

processes and mechanisms that determine the floristic composition, spatial distribution based

on environmental variables, and traditional knowledge of woody-plants in Neotropical

rainforests (Research gate). He has studied the patterns of plant use and value by rural and

indigenous people, plant-community ecology and relationships between people, plants and

habitats. He has also carried out quantitative ethno-botanical and economic botany studies in

Ecuador, Bolivia and Mexico. Macía has published tens papers about his research issues on

tropical botany and vegetation ecology (fp7 - palms).

Patiño Rodriguez, V. M. Historia y dispersión de los frutales nativos del Neotrópico.

(Centro Internacional de Agricultura Tropical - CIAT, 2002)

Víctor Manuel Patiño Rodríguez was an ethnobotanist and dedicated his life to the knowledge

and protection of the natural agricultural and forestry resources of Neotropico. He collected

species for the germplasm banks of several institutions and worked was an advisor to Botanic

Gardens of several cities in Colombia. He is the author of more than 29 books and other

38

publications on the subjects of agronomy, botany, economic botany, natural history,

anthropology and archaeology. In the book Historia y Dispersion de los Frutales Nativos del

Neotrópico, Patiño values the plants and animals present in the lives of people from the

American Ecuadorian region.

Revilla, J. (2002) Plantas úteis da bacia Amazônica 2vol. Manaus: Instituto Nacional de

Pesquisas da Amazônia/SEBRAE-AM

Juan Revilla is a Peruvian botanist and researcher at the National Institute of Amazonian

Research (INPA). Revilla conducted several works with economic botany and ethnobotany.

He also acts in the orientation of the use of Amazonian plants of medicinal value in the

treatment for many diseases (amazonia.org.br). Revilla published many scientific researches

in national and international journals about Amazonian flora and their landscape. In Plantas

úteis da bacia Amazônica, Revilla compiled information of several plant uses throughout the

Amazon basin (Revilla 2002).

de la Torre, L., Navarrete, H., Muriel, P., Marcia, M. & Balslev, H. Enciclopedia De

Plantas Utiles Del Ecuador. Herb. QCA la Esc. Ciencias Biológicas la Pontífica Univ.

Católica del Ecuador Herb. AAU del Departameto Ciencias Biológicas la Univ. Aarhus.

Quito Aarhus. 1, 1–3 (2008).

Lucía de la Torre is an ethnobotanist specialized in biodiversity informatics and web-based

presentation of data about useful plants. She has worked in ethnoecology of vines used by

Maya people in Southeast Mexico and in the relative importance of socioeconomic and

ecological factors in determining plant use patterns in Ecuador. Her scientific production

includes a catalogue of more than 5000 useful plants from Ecuador and its associated database

driven internet portal (fp7 - palms).

39

References

Amazônia: notícia e informação. In <http://amazonia.org.br>. Accessed in June 2018.

Congresso Colombiano de Restauração Ecológica 2018. In

<http://congreso2018.redcre.com>. Accessed in July 2018.

Fp7 – palms. In <http://www.fp7-palms.org>. Accessed in july 2018.

Meirelles Filho, João. Grandes Expedições à Amazônia Brasileira, Século XX. São Paulo:

Metalivros, 2009. 241 p.

Monumentos do Rio. In <http://www.monumentosdorio.com.br>. Accessed in June 2018.

Brasiliana Eletrônica. In <http://www.brasiliana.com.br>. Accessed in June 2018.

Research gate. In <www.researchgate.com>. Accessed in July 2018.

Revilla, J. 2002. Plantas úteis da bacia Amazônica. Manaus: INPA/SEBRAE.