UM EXEMPLO DE DESACELERAÇÃO DA SUCESSÃO NATURAL EM ...€¦ · 2 barbara machado caserio um...

Transcript of UM EXEMPLO DE DESACELERAÇÃO DA SUCESSÃO NATURAL EM ...€¦ · 2 barbara machado caserio um...

Universidade Federal de Ouro Preto – UFOP

Instituto de Ciências Exatas e Biológicas – ICEB

Departamento de Biodiversidade, Evolução e Meio Ambiente - DEBIO

__________________________________________________________________________

Dissertação de Mestrado

__________________________________________________________________________

UM EXEMPLO DE DESACELERAÇÃO DA SUCESSÃO NATURAL EM

FLORESTAS MONTANAS PÓS ABANDONO DE PLANTIO DE Camellia sinensis (L.)

Kuntze (Theaceae): O PAPEL POTENCIAL DE PIONEIRAS NATIVAS NA INIBIÇÃO

DA INVASÃO BIOLÓGICA.

Barbara Machado Caserio

Orientador: Prof. Dr. Sérvio Pontes Ribeiro/UFOP

Ouro Preto, MG

Novembro de 2015

2

BARBARA MACHADO CASERIO

UM EXEMPLO DE DESACELERAÇÃO DA SUCESSÃO NATURAL EM

FLORESTAS MONTANAS PÓS ABANDONO DE PLANTIO DE Camellia sinensis (L.)

Kuntze (Theaceae): O PAPEL POTENCIAL DE PIONEIRAS NATIVAS NA INIBIÇÃO

DA INVASÃO BIOLÓGICA.

Dissertação de Mestrado apresentada ao

Colegiado do Programa de Pós Graduação em

Ecologia de Biomas Tropicais da Universidade

Federal de Ouro Preto como parte dos

requisitos para obtenção do título de Mestre

em Ecologia de Biomas Tropicais

Orientador: Prof. Dr. Sérvio Pontes Ribeiro

Ouro Preto, MG

Novembro de 2015

3

Catalogação: www.sisbin.ufop.br

C338e Caserio, Barbara Machado. Um exemplo de desaceleração da sucessão natural em florestas montanas pós

abandono de plantio de Camellia sinensis (L.) Kuntze (Theaceae) [manuscrito]: o papel potencial de pioneiras nativas na inibição da invasão biológica / Barbara Machado Caserio. - 2015.

69f.: il.: color; grafs; tabs; mapas.

Orientador: Prof. Dr. Sérvio Pontes Ribeiro.

Dissertação (Mestrado) - Universidade Federal de Ouro Preto. Instituto de Ciências Exatas e Biológicas. Departamento de Biodiversidade, Evolução e Meio Ambiente. Ecologia de Biomas Tropicais.

1. Sucessão ecologica. 2. Plantas - Competição. 3. Camellia sinensis. 4. Bioinvasão. I. Ribeiro, Sérvio Pontes. II. Universidade Federal de Ouro Preto. III. Titulo.

CDU: 630*234

4

Agradecimentos

Agradeço, primeiramente, aos meus pais, por me apoiarem sempre durante toda essa

jornada.

Ao professor Sérvio pela oportunidade, confiança, acolhimento, profissionalismo,

competência, disposição, paciência e pela forma franca de orientação demonstrada durante a

execução deste trabalho, com sugestões fundamentais para o seu desenvolvimento.

Ao Paulo, pela ajuda e paciência em todos os momentos.

Aos alunos, ex-alunos e funcionários do LEEIDSN pelos bons momentos de

descontração, essenciais para o bom andamento de nossa equipe.

Aos amigos que foram encontrados durante esta caminhada (Jaque, Tássia, Grazi,

Bruninha, Leo, Diego, Letizia, Roberth, Renata, Cinthia) e os antigos que sempre estiveram

presentes.

Agradeço a todos que contribuíram para que este trabalho fosse realizado, tanto no

campo, como no laboratório, e nas discussões sobre estudos.

Ao Herbário José Badini pela colaboração efetiva dada a esse trabalho.

Aos técnicos do DEBIO que ajudaram, sempre que possível, e ao setor de transporte

da UFOP, que sempre atenderam as nossas demandas da melhor maneira possível.

Ao IEF, pela competência e agilidade no atendimento, e ao gerente do Parque Estadual

do Itacolomi, Juarez Távora Basíli, por todo apoio na execução deste trabalho. A

Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – CAPES, pela bolsa

concedida.

5

Sumário

RESUMO........................................................................................................................................................... 9

ABSTRACT ...................................................................................................................................................... 11

CAPÍTULO 1 .................................................................................................................................................... 13

1. REVISÃO TEÓRICA ......................................................................................................................................... 13

1.1. Histórico do conceito de sucessão natural ........................................................................................... 13

1.2. Sucessão em Florestas Tropicais Montanas brasileiras ......................................................................... 14

1.3. Monodominâncias ................................................................................................................................. 16

1.4. A Candeia (Eremanthus erythropappus) ............................................................................................... 18

1.5. Um histórico dos distúrbios em uma área de Floresta Montana do Parque Estadual do Itacolomi ..... 19

2. OBJETIVOS ..................................................................................................................................................... 23

2.1. Objetivo geral ........................................................................................................................................ 23

2.2. Objetivos específicos ............................................................................................................................. 23

3. REFERÊNCIAS BIBLIOGRÁFICAS ..................................................................................................................... 24

CAPÍTULO 2 .................................................................................................................................................... 31

ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................................................ 31

INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................ 32

METHODS ............................................................................................................................................................. 35

Study site ...................................................................................................................................................... 35

Tree census ................................................................................................................................................... 36

Data analysis ................................................................................................................................................ 37

RESULTS ............................................................................................................................................................... 38

Floristic composition and species diversity ................................................................................................... 38

Phytosociological parameters and community structure ............................................................................. 43

β-diversity ..................................................................................................................................................... 53

Camellia sinensis census in monodominance area, disturbed forest and native forest ............................... 53

DISCUSSION .......................................................................................................................................................... 54

6

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................................................ 60

LITERATURE CITED ............................................................................................................................................ 60

7

Lista de figuras

Capítulo 1

FIGURA 1: MAPAS DO USO E DE OCUPAÇÃO DA ÁREA DO PARQUE ESTADUAL DO ITACOLOMI DESDE 1966 (A); 1974 (B); 1986 (C) E

2000 (D). EM BRANCO A ÁREA DE CAMPO RUPESTRE, EM CINZA AS FLORESTAS ESTACIONAIS SEMIDECIDUAIS E EM PRETO AS

ÁREAS ANTROPIZADAS. (RETIRADAS DE FUJACO ET AL.(2010) E MODIFICADO POR CAMPOS (2012). ................................ 21

FIGURA 2: MAPA GEOMORFOLÓGICO DO PEIT (RETIRADAS DE FUJACO (2006)) ................................................................... 22

Capítulo 2

FIGURE 1: MONODOMINANCE AREA INDIVIDUALS DISTRIBUTION IN DIAMETER CLASSES (PBH ≥ 10CM) ...................................... 49

FIGURE 2: MONODOMINANCE AREA ECOLOGICAL GROUP DISTRIBUTION IN DIAMETER CLASSES (PBH ≥ 10CM) ............................ 50

FIGURE 3: MONODOMINANCE AREA INDIVIDUALS DISTRIBUTION IN HEIGHT CLASSES (MIN: 1.5M; MAX:8.0M) ........................... 50

FIGURE 4: MONODOMINANCE AREA ECOLOGICAL GROUP DISTRIBUTION IN HEIGHT CLASSES (MIN: 1.5M; MAX:8.0M) ................. 51

FIGURE 5: DISTURBED FOREST INDIVIDUALS DISTRIBUTION IN DIAMETER CLASSES (PBH ≥ 10CM) .............................................. 51

FIGURE 6: DISTURBED FOREST ECOLOGICAL GROUP DISTRIBUTION IN DIAMETER CLASSES (PBH ≥ 10CM) .................................... 52

FIGURE 7: DISTURBED FOREST INDIVIDUALS DISTRIBUTION IN HEIGHT CLASSES (MIN: 2.0M; MAX:11.0M) ................................. 52

FIGURE 8: DISTURBED FOREST ECOLOGICAL GROUP DISTRIBUTION IN HEIGHT CLASSES (MIN: 2.0M; MAX:11.0M) ....................... 53

FIGURE 9: IMPORTANCE VALUE INDEX (IVI) OF DEAD AND ALIVE E. ERYTHROPAPPUS IN MONODOMINANCE AREA, DISTURBED FOREST

AND NATIVE FOREST. ......................................................................................................................................... 58

8

Lista de tabelas

Capítulo 2

TABLE 1: FLORISTIC LIST OF TREE SPECIES IDENTIFIED AT THE MONODOMINANCE, THE DISTURBED FOREST AND THE NATIVE FOREST,

ARRANGED ALPHABETICALLY BY BOTANICAL FAMILIES AND THEIR ECOLOGICAL GROUPS (EG) (P: PIONEER; CL: LIGHT-

DEMANDING CLIMAX E CS: SHADE-TOLERANT CLIMAX), IN ITACOLOMI STATE PARK. ...................................................... 40

TABLE 2: PHYTOSOCIOLOGICAL PARAMETERS IN THE MONODOMINANCE AREA ....................................................................... 44

TABLE 3: PHYTOSOCIOLOGICAL PARAMETERS OF ECOLOGICAL GROUPS IN THE MONODOMINANCE AREA ...................................... 45

TABLE 4: PHYTOSOCIOLOGICAL PARAMETERS AT THE DISTURBED FOREST AREA ....................................................................... 47

TABLE 5: PHYTOSOCIOLOGICAL PARAMETERS OF ECOLOGICAL GROUPS AT THE DISTURBED FOREST AREA ...................................... 48

TABLE 6: PHYTOSOCIOLOGICAL PARAMETERS OF C. SINENSIS IN THE MONODOMINANCE AREA, DISTURBED FOREST AND NATIVE FOREST

..................................................................................................................................................................... 54

9

RESUMO

O conhecimento da estrutura e dinâmica de populações florestais é decisivo para

garantir o sucesso no manejo sustentável de florestas, além de contribuir para a compreensão

de processos ecológicos e evolutivos. Este trabalho foi realizado no Parque Estadual do

Itacolomi, Minas Gerais, onde o abandono do cultivo de chá (Camellia sinensis) levou ao

estabelecimento de uma monodominância da espécie pioneira Eremanthus erythropappus.

Testamos a hipótese de que a falta de manejo do chá levou a uma desaceleração no processo

de sucessão natural, além de verificar se há um gradiente sucessional da substituição de

espécies em direção à comunidade arbórea nativa. Três áreas foram amostradas: uma

caracterizada por dominância de E. erythropappus, uma área adjacente de Floresta Montana

com histórico de extrações de madeira e abertura de clareiras e um fragmento de Floresta

Montana Nativa. Foram feitas dez parcelas de 20x20m em cada, exceto na área de mata

nativa, e nelas foram identificados todos os indivíduos com CAP acima de 10cm, sendo que

as frequências, densidades, dominâncias e valores de importância e cobertura foram

determinados. Os resultados demonstraram que E. erythropappus é a espécie mais

representativa na área dominada por candeias. Além disso, o número elevado de indivíduos de

espécies pioneiras indicam que esta área se encontra ainda em um estágio inicial de sucessão.

Por outro lado, a comparação da diversidade com a área de mata impactada e com a mata

nativa mostra que há uma similaridade de 50% de espécies entre essas áreas, sugerindo que a

sucessão natural está progredindo para a composição florística da mata nativa. O maior valor

do IVI de E. erythropappus mortas na área de mata impactada e o valor decrescente no IVI de

E. erythropappus vivas indica que a permanência dessa espécie no sistema inibe o avanço da

sucessão. Foram encontrados 1,78 pés de C. sinensis por m² com uma altura média de 1m no

sub-bosque do fragmento de mata nativa, indicando uma invasão do chá na área de mata

nativa. A presença do chá atualmente na área de mata impactada e no fragmento de mata

10

nativa sugere que ele possa desacelerar a sucessão ou mesmo retroceder a estrutura florística

por invasão de áreas intocadas. Por outro lado, a virtual ausência do chá junto com candeia

demonstra que a capacidade inibitória desta espécie nativa, se por um lado desacelera a

sucessão na floresta, por outro pode prevenir a invasão de exóticas. Esse estudo mostra que

certas práticas agroflorestais mal manejadas nos trópicos podem causar a diminuição da

diversidade.

Palavras chave: sucessão natural por inibição, Eremanthus erythropappus, Camellia sinensis,

florestas montanas, invasores florestais, competição arbórea, plantios abandonados.

11

ABSTRACT

The knowledge of structure and dynamics of forest populations is decisive to ensure

success in sustainable forest management, and also collaborate with the understanding of

ecological and evolutive processes. This study was held in Itacolomi State Park, Brazil, where

the abandonment of the tea (Camellia sinensis) cultivation led to the establishment of an

Eremanthus erythropappus (Asteraceae) monodominance. We tested the hypothesis that large

monodominant populations of pioneer species may delay before facilitate natural succession,

regardless native or invasive species. Hence, the absence of the tea menegement led to a delay

in the natural succession process as well as the survival of E. erythroppapus large

populations. Three areas were sampled: an area characterized by the dominance of E.

erythropappus, a Montane Forest with history of timber extraction and gaps formation, and a

control preserved forest. Ten plots of 20x20m were settled in each area, except on the

preserved forest, and in them were identified all individuals above 10cm of breast height

circumference, which were analyzed in terms of frequency, density, dominances and

importance and coverage values. The results have shown that E. erythropappus is most

representative species in the candeias dominance area, in which high mortality of this species

suggest it may be a regressive population. Besides that, the high number of pioneer plants

indicates that this area is in an early successional stage. On the other way, the diversity

comparison with the disturbed area and with the native forest shows that there is a species

similarity of 50% between these areas, suggesting that the natural succession is progressing

towards the floristic composition of the native forest. The high IVI value of dead E.

erythropappus in the disturbed forest and the decreasing IVI value of living E. erythropappus

shows that the permanence of this species in the system inhibits the succession advancement.

In the native forest understory 1.78 individuals per square meter of C. sinensis were found,

12

with an average height of 1m, indicating an invasion of C. sinensis in the native forest. The

currently presence of tea at the disturbed forest and the native forest suggests that it can

refrain the succession or even reverse the floristic structure through invasion of untouched

areas. On the other hand, virtually absence of tea with E. erythropappus demonstrates that the

inhibitory ability of this native species, if for one hand decelerates the forest succession, by

the other can prevent the exotic invasion. This study shows that certain badly managed

agroforestry practices in the tropics can lead to a decrease in diversity.

Key-words: natural succession by inhibition, Eremanthus erythropappus, Camellia sinensis,

montane forests, forest invaders, tree competition, abandoned plantations.

13

CAPÍTULO 1

1. REVISÃO TEÓRICA

1.1. Histórico do conceito de sucessão natural

A ocorrência de uma degradação ambiental causada por ação antrópica ou natural

acarretará um processo de regeneração natural, no qual a cobertura vegetal da área será

reestabelecida (Götsch 1995, Martins 1990). Este processo pressupõe a mudança da

fisionomia e das populações num crescente em qualidade e quantidade de vida, e é chamado

de sucessão natural (Götsch 1995), dado ao acréscimo, subtração e subsequente alternância de

espécies que ocorre à medida que a comunidade vai progredindo em direção ao seu potencial

máximo de uso dos recursos.

Henry Chandler Cowles, em 1899, foi o pioneiro no estudo da sucessão vegetal, sendo

o primeiro a desenvolver um trabalho completo sobre séries sucessionais (Tansley 1935).

Posteriormente a Cowles, o estudo da sucessão vegetal foi desenvolvido e consolidado

principalmente por Clements (1916). De acordo com Clements o processo sucessional era

ordenado e previsível, no qual a comunidade vegetal seria análoga a um organismo, que

nasce, cresce, atinge a maturidade e morre. Segundo sua teoria, as mudanças na comunidade

vegetal tendem a convergir em direção a um estado clímax direcionado unicamente pelo clima

(Clements 1916).

A teoria de Clements foi criticada principalmente por Gleason (1926) e Tansley

(1935). Para Gleason (1926), as espécies presentes na comunidade vegetal respondiam

individualmente a variações de fatores ambientais, e as comunidades seriam o resultado

eventual da sobreposição da distribuição das espécies. Para Tansley (1935), fatores locais

14

como o substrato de origem e a posição topográfica poderiam determinar o desenvolvimento

de vegetação, e não unicamente o clima, conforme defendido por Clements. Tansley (1935)

sugeriu ainda que a sucessão é um processo contínuo, podendo ser interrompida por

catástrofes não relacionadas ao processo sucessional.

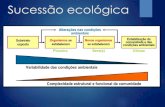

A partir do final do século XX as explicações para a sucessão assumiram o paradigma

de não-equilíbrio frente às condições do ambiente (Glenn-Lewin et al. 1992). Os estudos

passaram a buscar uma interpretação evolucionária, considerando mecanismos de interação

como competição e herbivoria. Também é importante ressaltar que este paradigma reconhece

uma multiplicidade de mecanismo reguladores, tanto bióticos quanto abióticos (Connell &

Slatyer 1977, Horn 1974, Picket 1976).

Nessa visão da dinâmica da vegetação subentende-se que os ecossistemas são sujeitos

a distúrbios constantes que afetam na composição, estrutura e funções das comunidades,

sendo que são concebidos como sistemas abertos e por isso sofrem influência de seu entorno.

1.2. Sucessão em Florestas Tropicais Montanas brasileiras

A sucessão secundária ocorre com a substituição da vegetação após uma perturbação

na vegetação que existia anteriormente (Glenn-Lewin & Van derMaarel 1992). Considerando

os mecanismos que determinam a sequência de espécies, em 1977 Connell & Slatyer

apresentaram três modelos de sucessão: por facilitação, tolerância e inibição. Nas florestas

montanas brasileiras, o modelo de regeneração observado tende a ser entendido como de

facilitação (Tabarelli & Mantovani 1999).

O modelo de facilitação, também chamado de sucessão obrigatória, é caracterizado

pela ocupação dos espaços abertos por uma ou mais espécies que, por sua vez, causam

modificações bióticas e abióticas no ecossistema que condicionam o ambiente de forma

15

favorável ao estabelecimento, crescimento ou desenvolvimento de outras espécies com

características ecológicas diferentes das colonizadoras. Desta forma, o estabelecimento de

espécies pioneiras é um pré-requisito para o estabelecimento de espécies de outros grupos

(Connell & Slatyer 1977).

Segundo Tabarelli & Mantovani (1999), nas florestas montanas a riqueza e a

diversidade de espécies são os primeiros componentes a retornarem a um estado próximo do

inicial, depois a composição de guildas, seguida da composição florística e, por último,

atributos de estrutura física (área basal e volume), exceto densidade de indivíduos. Além

disso, no processo de regeneração tende-se a aumentar o percentual de espécies zoocóricas, de

sub-bosque e de espécies tolerantes à sombra. Regenera-se, assim, dentro dos padrões

observados para as florestas tropicais.

Famílias como Myrtaceae, Melastomataceae, Leguminosae, Rubiaceae e Lauraceae

foram apontadas como de grande importância na estrutura e composição da Mata Atlântica

Sub-Montana e Montana do sudeste do Brasil (Tabarelli & Mantovani 1999, Oliveira-Filho &

Fontes 2000, Scudeller et al. 2001; Tabarelli & Perez 2002). A substituição das espécies se dá

com o desaparecimento de espécies pioneiras, nos estágios iniciais, como as do gênero

Baccharis (Asteraceae), Dalbergia (Leguminosae) e Tibouchina (Melastomataceae), e o

aparecimento de espécies de famílias como Myrtaceae, compostas em sua maioria por

espécies tolerantes a sombra, zoocóricas e espécies típicas de sub-bosque, nos estágios

avançados.

Além da substituição das espécies pioneiras por espécies tolerantes a sombra, nas

Florestas Montanas a regeneração também pode ocorrer através da substituição direcional das

formas de crescimento e história de vida (Tabarelli 1997). Desse modo, espécies de ervas,

arbustos, árvores pioneiras de ciclo de vida curto e longo constituem grupos ecológicos com

funções distintas na regeneração da floresta.

16

Em fases iniciais de sucessão pode ocorrer a dominância de uma única espécie

pioneira, que pode se estabelecer por períodos indeterminados, dependendo do distúrbio, da

intensidade e do local (Tabarelli & Mantovani 1999). Quando tais populações se estabelecem,

em especial em ecossistemas adaptados a solos edaficamente pobres, as mudanças das

condições abióticas relacionadas ao acúmulo da biomassa vegetal poderão ser lentas, e toda a

sucessão fica dependendo do longo ciclo de vida desta espécie, o que afeta inclusive a fauna

associada e a estrutura geomorfológica do solo (Costa et al. 2010). Desta maneira, mesmo que

a longo prazo haja um processo de sucessão por facilitação, por um certo período de tempo

esta espécie altamente dominante caracterizará uma inibição sucessional (Connell & Slatyer

1977).

1.3. Monodominâncias

As florestas tropicais são conhecidas por possuírem uma alta variedade de espécies.

Entretanto, florestas que apresentam o dossel dominado por uma única espécie arbórea podem

ser encontradas (Richards 1996). Florestas monodominantes tropicais são vegetações raras

onde uma única espécie ocupa mais de 60% do número de indivíduos ou da área basal total da

floresta (Connell & Lowman 1989). Estudos realizados na África demonstraram que uma

única espécie pode dominar mais do que 80% do dossel (Hart et al. 1989). A ocorrência de

florestas monodominantes foi relatada em vários lugares do mundo (Higashikawa 2009).

As monodominâncias são classificadas em dois tipos: persistentes e não persistentes

(Peh 2009). As persistentes se separam em três grupos: as florestas submetidas a inundações,

as florestas com baixo nível de nutrientes no substrato e as florestas monodominantes

clássicas (Peh 2009). As florestas monodominantes clássicas possuem 60% ou mais de seu

dossel formado por uma única espécie (Hart 1985, Connell & Lowman 1989, Hart et al.

17

1989), e uma dominância de cerca de 80 a 100% pode ser encontrada em alguns casos

(Connell & Lowman 1989). A espécie dominante não é pioneira e as florestas estão sob as

mesmas condições das florestas mistas. Atualmente existem muitas hipóteses que tentam

explicar do ponto de vista ecológico ou evolucionário os mecanismos envolvidos nas

monodominâncias clássicas. São eles: a ausência de distúrbios exógenos, a tolerância à

sombra e sobrevivência das sementes sob dossel denso, baixa taxa de decomposição - o que

leva a baixa disponibilidade de nutrientes, sementes grandes - que conseguem penetrar numa

camada grossa de serrapilheira, associações ectomicorrízicas, o padrão de frutificação, o

padrão de dispersão de sementes e a resistência à herbivoria (Peh 2009).

As monodominâncias não persistentes se estabelecem em áreas após distúrbios, sendo

assim consideradas florestas sucessionais (Gerhardt & Todd 2009, Nappo et al. 2000,

Tabarelli & Mantovani 1999). Segundo Peh (2009), essas espécies não conseguem crescer sob

seu próprio dossel e dessa forma se mantêm por uma ou poucas gerações. Vários estudos

sugerem que as monodominâncias podem ser um estágio no processo de sucessão natural

(Read et al. 1995, Torti et al. 2001, Hart et al. 1989 e 1995).

No Brasil, podemos encontrar monodominâncias de Peltogyne gracilipes Ducke

(Fabaceae), onde solos com alta concentração de magnésio estão ligados à perda de suas

folhas, o que durante a decomposição pode influenciar no recrutamento de outras espécies

(Nascimento & Proctor 1994). Também ligadas às altas concentrações de magnésio no solo

no Brasil são as monodominâncias de Brosimum rubescens Taub. (Moraceae), que também

sofrem a influência da alta acidez e baixa fertilidade do solo em áreas de transição entre

floresta Amazônia e o Cerrado (Marimon et al. 2001). Um exemplo de monodominâncias

permanentes encontradas no Brasil são as formadas por Tabebuia aurea (Bignoniaceae)

(Ribeiro & Brown 2006), Vochysia divergens (Vochysiaceae) e Copernicia alba (Arecaceae)

no Pantanal (Scremin-Dias et al. 2011). Estas monodominâncias pantaneiras estão ligadas à

18

adaptação dessas espécies ao hidroperíodo da região (Luttge 1997), e à ausência de

herbivoria, no caso de T. aurea (Ribeiro & Brown, 1999, 2002 e 2006). Outros exemplos de

monodominância em florestas brasileiras são atribuídos às espécies florestais Myracrodruon

urundeuva (Anacardiaceae) (Oliveira et. al 2014), Mimosa scabrella (Leguminosae) (Klein

1981), Tabebuia cassinoides (Armelin et. al 1996), Calophyllum brasiliense (Bendazoli et al

1996), e Araucaria angustifolia (Hueck 1972).

1.4. A Candeia (Eremanthus erythropappus)

A espécie Eremanthus erythropappus, conhecida popularmente como candeia,

pertence à família Asteraceae e é uma espécie muito característica das florestas estacionais

semideciduais do sudeste brasileiro e comum, também, em campos rupestres e florestas

mesófilas, estabelecendo-se nestas últimas após perturbações (Oliveira Filho et al. 2004). É

caracterizada pela alta resistência, durabilidade e poder energético de sua madeira. Possui um

óleo essencial cujo princípio ativo, o α-bisabolol, exibe propriedades antiflogísticas,

antibacterianas, antimicóticas e dermatológicas (Pedralli 1997).

Vários estudos consideram as candeias parte do grupo ecológico das pioneiras, pelo

fato de serem exigentes quanto à luz durante o desenvolvimento (CETEC 1996, Carvalho

1994, Campos 2012). Um candeal, consequentemente, é uma formação pioneira de uma

população dominante de E. erythropappus, que se estabelece após a perturbação da floresta. O

número de indivíduos de candeia nesta formação diminui, gradativamente, à medida que a

floresta se torna mais estruturada: nos estágios intermediários de sucessão podem ser

observados indivíduos de maior porte, que vão desaparecendo na medida em que o dossel se

forma e os indivíduos de candeia vão sendo sombreados pelos das outras espécies (Pedralli

1997, Schorn e Galvão 2006, Silva 2001).

19

Os candeais se comportam similarmente a matas com espécies arbóreas típicas de

estágios sucessionais iniciais (CETEC 1996, Santana 2010, Silva 2001, Werneck et al. 2000).

Isso indica que, após uma perturbação, a predominância de candeias pode ser considerada um

estágio inicial de uma sucessão secundária (Hart et al. 1989).

Esta situação pode ser aplicada, por um lado, no modelo de facilitação, que diz que as

fases iniciais da sucessão natural podem ser dominadas por uma única espécie pioneira, que

pode se estabelecer por períodos indeterminados, mas ao longo de sua existência alterar o solo

e outros elementos do habitat, facilitando a entrada de novas espécies (Connell & Slatyer

1977). Este modelo aplica-se quando se olha para o candeal e para fauna típica de ambientes

florestais, que certamente são atraídas pela presença das condições microclimáticas criadas

pela população de candeia. Por outro lado, a predominância competitiva de um candeal pode

também configurar uma inibição relativa no que tange a outras espécies arbóreas. Por

décadas, embora modifique e crie condições edáficas para uma floresta mais diversa, a

candeia de fato exibirá uma ação inibitória para outras espécies de árvores, como descrito em

Campos (2012).

1.5. Um histórico dos distúrbios em uma área de Floresta Montana do Parque

Estadual do Itacolomi

O Parque Estadual do Itacolomi possui cerca de 7.543 ha, e localiza-se ao sul da

Cadeia do Espinhaço, entre os municípios de Ouro Preto e Mariana. Possui altitudes variando

entre 900 e 1772 m, cujo ponto mais alto é o Pico do Itacolomi. O clima da região é do tipo

Cwb, subtropical úmido com inverno seco e verão temperado, de acordo com a classificação

20

climática de Köppen (Álvares et al. 2013). As temperaturas médias anuais oscilam entre 17,4

e 19,8°C (Lourenço 2015).

Em termos geológicos, a região pertence à porção sudeste do Quadrilátero Ferrífero.

De acordo com Ferreira & Magalhães (1977 apud Kamino et al. 2008), os solos na Cadeia do

Espinhaço são rasos, pobres e pedregosos com baixa capacidade de retenção de água.

Localmente, a geomorfologia do Parque consiste na presença de quartzito ferruginoso,

depósitos de elúvios-coluviais (canga), quartzitos e metaconglomerados, associação de xisto e

quartzito ferruginoso (Fujaco 2007).

Devido à elevada heterogeneidade ambiental, a cobertura vegetal apresenta ampla

diversificação fisionômica, sendo que as principais formações fitofisionômicas encontradas

no Parque são as campestres, como os Campos Rupestres, e as florestais, com Floresta

Estacional Semidecidual Montana (Veloso et al. 1991).

A área do Parque tem um longo histórico de ocupação (Figura 1), que remete ao

período colonial e à exploração do ouro, seguida pelo surgimento das grandes fazendas e das

plantações de chá preto (Camellia sinensis) até cerca de 1950, sendo a mais importante a

Fazenda do Manso, onde hoje em dia se encontra a sede do Parque e suas principais

estruturas. Após o fim das exportações de chá, a região passou a ser utilizada por grandes

empresas para desmatamento para plantio de eucalipto e produção de carvão em altos fornos

(Fujaco et al. 2010). Em 1967, foi criada a Unidade de Conservação.

21

Figura 1: Mapas do uso e de ocupação da área do Parque Estadual do Itacolomi desde 1966

(A); 1974 (B); 1986 (C) e 2000 (D). Em branco a área de campo rupestre, em cinza as

Florestas Estacionais Semideciduais e em preto as áreas antropizadas. (Retiradas de Fujaco et

al.(2010) e modificado por Campos (2012).

As plantações de chá foram abandonadas, sem a aplicação de nenhuma técnica de

manejo, e a regeneração aconteceu naturalmente com a substituição dos indivíduos de C.

sinensis pelos de E. erythropappus, caracterizando o estabelecimento de uma

monodominância de candeia. Além disso, em áreas da floresta adjacente às plantações de chá

ocorreram aberturas de clareiras com a extração pontual de madeira para a alimentação dos

fornos.

O estudo foi realizado no Parque Estadual do Itacolomi (PEIT), em um candeal às

margens da Trilha do Forno e na mata estacional semidecidual adjacente, entre as

coordenadas 20°25'50"S; 43°30'31"W and 20°25'42"S; 43°30'20"W. Conforme classificado

22

por Fujaco (2007), ambas as áreas se encontram na unidade geomorfológica 1 (UM_1)

apresentado uma litologia em sua maioria de filitos e xistos, e em menor escala de quartzitos

ferrugionosos e cangas (Figura 2).

Figura 2: Mapa Geomorfológico do PEIT (Retiradas de Fujaco (2006))

23

2. OBJETIVOS

2.1. Objetivo geral

O presente trabalho teve como objetivo comparar a composição florística e a estrutura

da comunidade arbórea de uma área onde houve o abandono da monocultura de chá (C.

sinensis), com posterior estabelecimento de uma população dominante de candeia (E.

erythropappus), e a área adjacente de floresta manejada, de forma a inferir processos

sucessionais e dinâmicas de substituição de espécies.

2.2. Objetivos específicos

Verificar a composição florística e os parâmetros fitossociológicos e estruturais em

ambas as áreas sucessionais estudadas no PEIT.

Verificar se há invasão de chá (C. sinensis) na área de mata nativa adjacente à área de

estudo.

Testar a hipóteses de que espécies pioneiras capazes de formar densas populações

podem causar inibição da sucessão natural antes de iniciarem modificações

facilitadoras. Desta hipótese testaremos duas predições: (1) a não-eliminação das

plantas do chá após o fim da fazenda levou a uma desaceleração no processo de

sucessão natural em áreas degradas devido à invasão dessa espécie; (2) processos de

mortalidade em candeais resultam em uma comunidade arbórea sendo substituída em

direção à composição florística de mata nativa adjacente.

24

3. REFERÊNCIAS BIBLIOGRÁFICAS

ALVARES, C.A.; STAPE, J.L.; SENTELHAS, P.C.; GONÇALVES, J.L.M.; SPAROVEK,

G. 2013. Ko¨ppen‟s climate classification map for Brazil. Meteorologische Zeitschrift , v. 22,

n. 6, p. 711-728.

ANTUNES, F.Z. 1986. Caracterização climática do Estado de Minas Gerais. Informe

Agropecuário, v.12, n.138, p.9-13.

ARMELIN, M. J. C.; PINHEIRO, L. A. V.; PAULO, R. A.; MARCHESINI, M.; VIANA, V.

M. 1996. Levantamento, localização, dimensionamento e caracterização das florestas de

Tabebuia cassinoides (Lam) DC. em São Sebastião. In: FOREST, 4., 1996, Belo Horizonte.

Biosfera, 1996. p. 122-123.

BENDAZOLI, A.; D‟ERCOLE, R. L.; LAM, M. 1996. Descrição da dinâmica da vegetação

de restinga no estado de São Paulo. In: FOREST, 4., 1996, Belo Horizonte. Biosfera, 1996. p.

208-209.

CAMPOS, N. R. 2012. Aptidão reprodutiva e estrutura de um candeial com elevada

mortalidade. 90f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Ecologia de Biomas Tropicais) - Universidade

Federal de Ouro Preto, Ouro Preto.

CARVALHO, P. E. R. 1994. Espécies florestais brasileiras: recomendações silviculturais,

potencialidade e uso da madeira. Brasília: EMBRAPA-CNPF, 640 pp.

CETEC-1996. Ecofisiologia da „candeia‟. Belo Horizonte: SAT/CETEC, 104 pp. (Relatório

técnico).

CLEMENTS, F. E. 1916. Plant Succession. Carnegie Institution, Publication 242,

Washington, D.C.

25

CONNELL, J.H. & SLATYER, R.O. 1977. Mechanisms of succession in natural

communities and their role in community stability and organization. American Naturalist

111:1119-1144.

CONNELL, J.H. & LOWMAN, M.D. 1989. Low-diversity tropical rain forests: some

possible mechanisms for their existence. American Naturalist, 134, 88–119.

COSTA, C. B., RIBEIRO, S. P., CASTRO, AMORIM, P.T. 2010. Ants as Bioindicators of Natural

Succession in Savanna and Riparian Vegetation Impacted by Dredging in the Jequitinhonha River

Basin, Brazil. Restoration Ecology. , 63: 148 - 157.

FERREIRA, M.B. & MAGALHÃES, G.M. 1977. Contribuição para o conhecimento da

vegetação da Serra do Espinhaço em Minas Gerais (Serra do Grão Mogol e da Ibitipoca). IN:

Congresso Nacional de Botânica, 26, Rio de Janeiro, 1975. Anais ... Rio de Janeiro. p. 189-

202.

FUJACO, M.A.G.; LEITE, M.G.P.; RIBEIRO, S.P. AND ORNELAS, A.R. 2006. Controle

geomorfológico e antrópico na distribuição de cadeias (Eremanthus sp.) no Parque Estadual

do Itacolomi, Minas Gerais. In: VI Simpósio Nacional de Geomorfologia, Goiânia.

FUJACO, M. A. G. 2007. Influência dos Diferentes tipos de Substrato e Geomorfologia na

Distribuição Espacial e Estrutura Arquitetônica do gênero Eremanthus sp., no Parque

Estadual do Itacolomi, Ouro Preto/MG. Dissertação de mestrado apresentado no Programa de

Pós-Graduação em Evolução Crustal e Recursos Naturais. Universidade Federal de Ouro

Preto. 113 pp.

FUJACO, M. A. G., LEITE, M. G. P. & MESSIAS, M. C. T. B. 2010. Análise multitemporal

das mudanças no uso e ocupação do Parque Estadual do Itacolomi (MG) através de técnicas

de geoprocessamento. Revista Escola de Minas 63: 695-701.

26

GERHARDT, K. & TODD, C. 2009. Natural regeneration and population dynamics of the

tree Afzelia quanzensis in woodlands in Southern Africa. African Journal of Ecology 47: 583 -

591.

GLEASON, H. A. 1926. The individualistic concept of the plant association. Bulletin Torrey

Botanical Club 53:7-26.

GÖTSCH, E. Break-through in agriculture. Rio de Janeiro: AS-PTA. 1995. 22p.

GLENN-LEWIN, D.C. & MAAREL, E. van der. 1992. Pattern and process of vegetation

dynamics. In: Glenn-Lewin, D.C.; Peet, R.K. & Veblen, T.T. (Eds). Plant Succession: theory

and prediction. Chapman & Hall. pp.11-59.

GLENN-LEWIN, D.C., PEET, R.K. & VEBLEN, T.T. 1992. Plant succession: theory and

prediction. Chapman & Hall, London.

HART, T.B. 1985. The ecology of a single-species-dominant forest and of a mixed forest in

Zaire, Africa. Ph.D. Thesis, Michigan State University, USA.

HART, T.B., HART, J.A. & MURPHY, P.G. 1989. Monodominant and species-rich forests in

the humid tropics: causes for their co-occurrence. American Naturalist, 133, 613–633.

HIGASHIKAWA, E. M. 2009. Fitossociologia de um fragmento florestal com

monodominância de Euterpe edulis Mart. 36 p. Dissertação (Mestrado em Engenharia

Florestal)-Universidade Federal de Lavras, Lavras.

HORN, H.S. 1974. The ecology of secondary succession. Annual Review Ecology and

Systematics 5:25-37.

HUECK, K. 1972. A região das matas de araucária do sul do Brasil. As florestas da América

do Sul: ecologia, composição e importância econômica. São Paulo: UnB/Polígono. Cap. 22,

p. 206-239.

27

KAMINO, L. H. Y.; OLIVEIRA-FILHO, A. T.; STEHMANN, J. R. 2008. Relações

florísticas entre as fitofisionomias florestais da Cadeia do Espinhaço, Brasil. Revista

Megadiversidade, vol. 4, n. 1-2. Dezembro.

KLEIN, R. M. 1981. Aspectos fitossociológicos da bracatinga (Mimosa scabrella). In:

Seminário sobre atividades e perspectivas florestais, Curitiba. 1981, Anais... Curitiba: p. 145-

148

LIMA, G. P. de. 2009. Avaliação do regime hídrico, geológico e geomorfológico das

florestas paludosas do Parque Estadual do Itacolomi: Influência dos fatores abióticos sobre a

composição florística e fitossociológica. 68p. Dissertação (Mestrado em Evolução Crustal e

Recursos Naturais) - Universidade Federal de Ouro Preto, Ouro Preto, 2009.

LOURENÇO, G.M., CAMPOS, R.B.F. & RIBEIRO, S.P. 2015. Spatial distribution of insect

guilds in a tropical montane rainforest: effects of canopy structure and numerically dominant

ants. Arthropod-Plant Interactions.

LÜTTGE, U. 1997. Physiological ecology of tropical plants. Springer, New York.

MARIMON, B. S.; FELFILI, J. M.; HARIDASAN, M. 2001. Studies in monodominant

forests in eastern Mato Grosso Brazil: I. A forest of Brosimum rubescens Taub. Edinburgh

Journal of Botany, 58(1):123-137.

MARTINS, F. R. 1990. Esboço histórico da fitossociologia florestal no Brasil. In: Congresso

Brasileiro de Botânica, 36. Brasília. Anais... Brasília, 1990. p. 33-58.

NAPPO, M. E., FONTES, M. A. L. & OLIVEIRA FILHO, A. T. 2000. Regeneração natural

em sub-bosque de povoamentos homogêneos de Mimosa scabrella Bentham, implantados em

áreas mineradas, em Poços de Caldas, Minas Gerais. Árvore 24: 297-307.

NASCIMENTO, M. T., AND J. PROCTOR. 1994. Insect defoliation of a monodominant

Amazonian rainforest. J. Trop. Ecol. 10: 633–636.

28

OLIVEIRA, F.P.; SOUZA, A.L.; FILHO, E. I.F. 2014. "Caracterização da monodominância

de aroeira (Myracrodruon urundeuva Fr. All.) no município de Turumitinga – MG". Ciência

Florestal, num. Abril-Junho, pp. 299-311.

OLIVEIRA-FILHO A.T. & FONTES, M.A.L. 2000. Patterns of floristic differentiation

among Atlantic Forests in Southeastern Brazil and the influence of climate. Biotropica

32:793-810.

OLIVEIRA-FILHO, A.T., CARVALHO, D.A., FONTES, M.A.L., VAN DEN BERG, E.,

CURI, N. & CARVALHO, W.A.C. 2004. Variações estruturais do compartimento arbóreo de

uma floresta semidecídua alto-montana na chapada das Perdizes, Carrancas, MG. Revista

Brasileira de Botânica 27:291-309.

PEDRALLI, G. 1997. Estrutura diamétrica, vertical e análise do crescimento da „candeia‟

(Vanillosmopsis erythropappa Sch. Bip) na Estação Ecológica do Tripuí, Ouro Preto – MG.

Revista Árvore 21: 301-306.

PEH, K.S. 2009. The relationship between species diversity and ecosystem function

in low- and high-diversity tropical African forests. Ph.D. thesis, University of Leeds, Leeds.

PICKETT, S.T.A. 1976. Succession: an evolutionary interpretation. American Naturalist

110:107-119.

READ, J., HALLAM, P. & CHERRIER, J.-F. 1995. The anomaly of monodominant tropical

rainforests: some preliminary observations in the Nothofagus-dominated rainforests of New

Caledonia. Journal of Tropical Ecology 11: 359–389.

RIBEIRO, S. P. & BROWN, V. K. 1999. Insect Herbivory In Tree Crowns Of Tabebuia

Aurea And T. Ochracea (Bignoniaceae): Contrasting The Brazilian Cerrado With The

Wetland Pantanal Matogrossense. Selbyana 20:159-170.

29

RIBEIRO, S. P. & BROWN, V. K. 2002. Tree species monodominance or species-rich

savannas: the influence of abiotic factors in designing plant communities of the Brazilian

cerrado and the Pantanal matogrossense - a review. Ecotropica 8: 31-45.

RIBEIRO, S. P. & BROWN, V. K. 2006. Prevalence of monodominant vigorous tree

populations in the tropics: herbivory pressure on Tabebuia species in very different habitats.

Journal of Ecology 94: 932–941.

RICHARDS, P.W. 1996. The Tropical Rain Forest, 2nd edn, Cambridge University Press,

Cambridge.

SANTANA, G. da C. 2010. Estrutura de uma floresta ombrofila densa montana com

monodomiancia de dossel por Eremanthus erythropappus (DC.) MacLeish (candeia) Serra da

Mantiqueira, em Itamonte, Minas Gerais. Dissertação (mestrado) – Universidade Federal de

Lavras. 58 pp.

SCHORN, L. A.; GALVÃO, F. 2006. Dinâmica da regeneração natural em três estágios

sucessionais de uma Floresta Ombrófila Densa em Blumenau, SC. Revista Floresta, Curitiba,

36: 59-74.

SCREMIN-DIAS, E., LORENZ-LEMKE, A. P. & OLIVEIRA, A. K. M. 2011. The floristic

heterogeneity of the Pantanal and the occurrence of species with different adaptive strategies

to water stress. Brazilian Journal of Biology 71: 275-282.

SCUDELLER, V.V., MARTINS, F.R. & SHEPHERD, G.J. 2001. Distribution and

abundance of arboreal species in the atlantic ombrophilous dense forest in Southeastern

Brazil. Plant Ecol. 152:185-199.

SEMAD/ IEF/ PROMATA. 2007. Plano de Manejo do Parque Estadual do Itacolomi.

Relatório técnico. 236 pp.

30

SILVA, E. F. 2001. Caracterização edáfica e fitossociológica em áreas de ocorrência natural

de candeia (Vanillosmopsis erythropappa Sch. Bip.). 118 p. Dissertação (Mestrado em

Engenharia Florestal) - Universidade Federal de Viçosa, Viçosa MG, 2001.

TABARELLI, M. 1997. A regeneração da floresta Atlântica montana. Tese de Doutorado,

Instituto de Biociências, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo.

TABARELLI, M. & MANTOVANI, W. 1999. A regeneração de uma floresta tropical

montana após corte e queima (São Paulo – Brasil). Revista Brasileira de Biologia 59: 239-

250.

TABARELLI, M.; PERES, C. A. 2002. Abiotic and vertebrate seed dispersal in Brazilian

Atlantic Forest: implications for forest regeneration. Biological Conservation, v.106, n.2,

p.165-176.

TANSLEY, A. G. 1935. The use and abuse of vegetational concepts and terms. Ecology 16:

284-307.

TORTI, S.D., COLEY, P.D. & KURSAR, T.A. 2001. Causes and consequences of

monodominance in tropical lowland forests. The American Naturalist 157: 141–153.

VELOSO, H.P., RANGEL-FILHO, A.L.R. & LIMA, J.C.A. 1991. Classificação da

vegetação brasileira, adaptada a um sistema universal. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE. 124 pp.

WERNECK, M.S., PEDRALLI, G., KOENIG, R. & GISEKE, L.F. 2000. Florística e

estrutura de três trechos de uma floresta semidecídua na Estação Ecológica do Tripuí, Ouro

Preto, MG. Revista Brasileira de Botanica 23: 97-106.

31

CAPÍTULO 2

AN EXEMPLE OF NATURAL SUCCESSION DECELERATION IN MONTANE

FORESTS AFTER THE CULTURE ABANDONMENT OF Camellia sinensis (L.)

Kuntze (Theaceae): THE ROLE OF PIONEER NATIVE SPECIES IN BIOLOGIC

INVASION INHIBITION

ABSTRACT

This study was held in Itacolomi State Park, Brazil, where the abandonment of tea

(Camelia sinensis) cultivation led to the establishment of an Eremanthus erythropappus

(Asteraceae) monodominance. We tested the hypothesis that large monodominant populations

of pioneer species, regardless native or invasive, may delay before facilitate natural

succession. We sampled an area characterized by dominance of E. erythropappus, a Montane

Forest with history of timber extraction and gaps formation, and a control native forest. Ten

plots of 20x20m were settled in each area, except for the native forest, and in there were

identified all individuals above 10cm of breast height circumference, which had their

phytosociological parameters analyzed. The results have shown that the high number of

pioneer plants in the candeia dominance area indicates that this area is in an early

successional stage. The diversity comparison with the disturbed forest and the native forest

shows a species similarity of 50% between these areas, suggesting that the natural succession

is progressing towards the floristic composition of the native forest. The high Importance

Value Index (IVI) value of dead E. erythropappus in the disturbed forest and the decreasing

IVI value of living E. erythropappus shows that the permanence of this species in the system

inhibits the succession advancement. In the native forest understory 1.78 individuals per

square meter of C. sinensis were found, indicating an invasion of C. sinensis in this area. The

32

current presence of tea at both disturbed and native forests suggests that it can refrain the

succession or even reverse the floristic structure through invasion of untouched areas. On the

other hand, virtual absence of tea with E. erythropappus demonstrates that the inhibitory

ability of this native species, if for one hand decelerates the forest succession, on the other can

prevent the exotic invasion. This study shows that certain badly managed agroforestry

practices in the tropics can lead to a decrease in diversity.

Key-words: natural succession by inhibition, Eremanthus erythropappus, Camellia sinensis,

montane forests, forest invaders, tree competition, abandoned plantations.

INTRODUCTION

Disturbances caused by human activities occurs since antiquity, with deforestation and

livestock as the main consequences. With the increasing of the demand for fertile, flat and

arable land, natural vegetation has been reduced, drastically pressing natural resources (Souza

2004). The forest fragmentation process has been getting more attention lately due to high

deforestation rates and their effects in tropical regions (Viana et al. 1997). The degradation

caused by both human and natural actions will result in a natural succession process, in which

the vegetation will be re-established (Götsch 1995, Martins 1990).

Neotropical Montane Forests are extremely biodiverse, and considered a high priority

for conservation especially regarding to its diversity of plants. Nevertheless, they are the most

unknown and threatened of all the tropics vegetations (Gentry 1995). In Brazilian Montane

Forests, the observed natural succession seemed to match Connell and Slatyer´s facilitation

model (Tabarelli & Mantovani 1999).

33

The facilitation model occurs when one or more species occupy the disturbed area, and

alter the environment making it more suitable for the establishment, growth or development

of other species with different ecological characteristics, considering that the establishment of

pioneer species is a prerequisite for the establishment of species from other ecological groups

(Connell & Slatyer 1977). Nevertheless, in early stages of forest succession, the dominance

by a single pioneer tree species may occur, which can be established for indefinite periods

thus causing inhibition before starting environmental changes that will facilitate the

establishment of other tree species (Tabarelli & Mantovani 1999).

Monodominant forests occur when one species occupies more than 60% of the total

amount of individuals or the basal area of the forest (Connell & Lowman 1989), and are

classified into two types: persistent and non-persistent (Peh 2009). The classical

monodominant forests have 60% or more of their canopy formed by a single species, and the

dominant species is not pioneer (Hart 1985, Connell & Lowman 1989, Hart et al. 1989).

Non-persistent monodominances settle in areas after disturbances, and are therefore

considered successional forests (Gerhardt & Todd 2009, Nappo et al. 2000, Tabarelli &

Mantovani 1999). According to Peh (2009), these species cannot grow under its own canopy

and remain for one or few generations. Several studies suggest that tropical monodominances

may be an early stage in the natural succession process (Read et al. 1995, Torti et al. 2001,

Hart 1989, 1995).

In Brazil, monodominances of many species can be found (Villela & Proctor 1999;

Marimon et al. 2001; Ribeiro & Brown 1999, 2002 and 2006, Scremin-Dias et al. 2011;

Oliveira et. al 2014, Klein 1981, Armelin et. al 1996, Bendazoli et al 1996, Hueck 1972). In

montane forests or transitions to high altitude grasslands, monodominant formations of

Eremanthus erythropappus (DC.) MacLeish (Asteraceae) were registered by Silva (2001),

Fujaco (2007), Souza (2007), Rosumek (2008), Araújo (2012) and Campos (2012).

34

Eremanthus erythropappus, known as “candeia” (Pio-Correa 1984), is considered a

pioneer species because it has a high demand of light during its development (CETEC 1996,

Carvalho 1994, Campos 2012). It‟s an usual plant species in semideciduous forests in

southeastern Brazil, and is also common in campos rupestres (rocky outcrops or high altitude

grasslands) and rainforests (Oliveira Filho et al. 2004). A “candeal” is a pioneer formation of

an E. erythropappus dominant population that settled after the forest disturbances.

Eremanthus erythropappus numbers decrease gradually as the forest becomes more

structured, showing that the predominance of this species can be considered an early stage of

a secondary succession (Hart et al. 1989, Pedralli 1997, Schorn & Galvão 2006, Silva 2001,

Campos 2012).

The Itacolomi State Park in southeastern Brazil has a well-known historic of anthropic

impacts since the sixteenth century. About 50 years ago, the abandonment of the black tea

(Camellia sinensis (L.) Kuntze (Theaceae) cultivation led to the establishment of an E.

erythropappus monodominance (Fujaco 2007). In this study we tested the hypothesis that

pioneer species able to form dense populations can cause inhibition of natural succession

before starting facilitate modifications. This hypothesis will test two predictions: (1) The

failure to eliminate tea plants after the end of the farm led to a refrained natural succession

process in degraded areas due to the invasion of this species; (2) Eremanthus erythropappus

mortality processes result in a tree community being replaced towards the floristic

composition of adjacent native forest.

35

METHODS

Study site

Itacolomi State Park has about 7543 hectares and is located in the southern portion of

the Espinhaço mountain range, between the cities of Ouro Preto and Mariana, with altitudes

ranging between 900 and 1772m. The climate is classified by Koppen as Cwb, humid

subtropical with dry winters and temperate summers (Álvares et al. 2013). Temperatures

range from 17.4 to 19.8°C (Lourenço 2015). The area is formed by phyllites, schist, quartzite

and ferrugineous rocky (Fujaco 2007). Due to the high environmental heterogeneity, the

vegetation has a very diversified physiognomy, and the main phytophysionomic formations

found in the Park are the campestral, with campos rupestres, and forest, with montane forests

(Veloso et al. 1991).

The Park area has a long history of occupation, referring to the colonial period and

gold exploration, followed by the creation of large farms and the black tea cultures until the

fifties. After the end of the tea export, the tea culture areas were abandoned (Fujaco et al.

2010). In 1967 the protected area was established. Where black tea culture existed,

regeneration happened naturally with settlement of E. erythropappus monodominances. This

well-known land use is a unique example of the way vegetation changed during the creation

of the park (Fujaco et al. 2010, Lourenço et al. 2015).

The study was held in an E. erythropappus monodominance next to the "Trilha do

Forno" and in the adjacent area, a Montane Forest with history of timber extraction and gaps

formation, and compared with another better preserved forest, using the work done by Lima

(2009). Those areas are located between the coordinates 20°25'50"S; 43°30'31"W and

36

20°25'42"S; 43°30'20"W. As classified by Fujaco (2007), both areas have a phyllites and

schist lithology.

Tree census

For the tree census of the area dominated by E. erythropappus and for the disturbed

area ten 20x20m plots were allocated in each area, making a total sample area of 0.8ha. None

of the selected plots were located adjacent to each other, leaving a gap of at least 20m

between them. Within each plot all the arboreal individuals, alive or dead, with perimeter at

breast height (PBH) ≥ 10 cm were labeled. Individuals with bifurcated trunks which were at

or below PBH and with at least one ramification ≥10cm in PBH were measured separately.

The individuals were labeled in loco with numbered plates, and had their number, plot

number, botanical identification when known, PBH and full estimated height registered, and

plant material samples were collected. The areas were visited once a month, from

September/2013 to March/2015.

In the work done by Lima (2009) in the native forest, twenty-one plots were allocated,

making a total sample area of 0.63 ha. Within each plot all the arboreal individuals, alive or

dead, with perimeter at breast height (PBH) ≥ 15 cm were labeled. The number of individuals

and species were recorded, and the total height of each individual estimated with the help of a

graduated stick.

It was possible to identify dead E. erythropappus by the peculiar wood odor of the

species, caused by secondary metabolites. Some vegetative characteristics of the trunk such as

thick bark, with many cracks and white or gray sapwood were also used to recognize dead E.

erythropappus individuals (Scolforo et al. 2003, Mori 2008).

37

All the collected specimens were identified by comparison with the herbarium

specimens of the Herbarium "Professor José Badini" (OUPR) of the Universidade Federal de

Ouro Preto and consultations of current literature. They were herborized and incorporated at

OUPR. The species were classified in families recognized by the Angiosperm Phylogeny

Group III system (APG III 2009). The specific epithets and citations of the authors of the

species were standardized on the basis of the Lista de Espécies da Flora do Brasil (2015)

(List of Species of the Brazilian Flora) and on the website The Plant List (2015).

All species were classified into ecological groups, and the classification was based in

the light requirements, referring to work done in forests with similar vegetation. These studies

used the Swayne & Whitmore (1988) classification, cited by Botelho et al. (1995). The

groups defined were: pioneers (P), light-demanding climax (CL) and shade-tolerant climax

(CS) species.

To verify the presence of C. sinensis in the studied areas we used the Point-Centred

Quarter Method (PCQM) of Cottam & Curtis (1956). Three transects were established 100m

away from each other. In each transect there was a point every 10m, totaling 10 points for

transect. For each point, the distance and height of the four individuals of C. sinensis nearest

to the point in each quarter was registered. The inclusive criteria was a minimum height of

50cm.

For β-diversity comparisons we used phytosociological data obtained by Lima (2008)

of an area of native forest adjacent to the study area.

Data analysis

The diversity of woody species was determined using the Shannon-Wiener Diversity

Index (H') and Pielou`s Evenness or Equitability Index (J‟) (Brower et al. 1990), and the

38

phytosociological parameters (Mueller-Dombois & Ellenberg 1974) commonly used in forest

surveys, including: relative frequency (FR), relative density (RD), relative dominance (DoR),

importance index value (IVI) and coverage value index (CVI) calculated using Fitopac 2.1

(Shepherd 2010). The density of individuals with PBH > 10 cm and PBH > 15 cm was

computed and the ratio of these two was taken as a measure of the proportion of small and

large-sized individuals (Grubb et al. 1963). The range of diameter and height classes was

determined by Spiegel formula (Felfili & Resende 2003). The patterns of species population

structure were established based on density of species in different PBH and height classes and

interpreted as indication of variation in population dynamics.

To verify β-diversity, comparisons between the areas were made using the Sørensen

similarity index based on the presence or absence of species (Mueller-Dombois & Ellenberg

1974).

To check the variance of PBH and total height between the plant categories (alive E.

erythropappus, dead E. erythropappus, other species and ecological groups) a one-way

ANOVA was used in each variable, using the software Mini Tab (McCune & Mefford 1997).

The density, frequency and medium height of C. sinensis in all areas were calculated

in Excel using the formulae according to Brower and Zar (1984).

RESULTS

Floristic composition and species diversity

In both E. erythropappus dominated and disturbed areas a total of 1771 individuals

were sampled, belonging to 25 families, 39 genera and 56 species, with an amount of 131

dead individuals, of which 84 were E. erythropappus and 47 other species.

39

In the native forest there were sampled 2127 individuals belonging to 32 families, 54

genera and 84 species.

At the area with E. erythropappus dominance, we sampled 941 individuals belonging

to 16 families, 26 genera and 39 species; 69 dead individuals were identified, of which 54

were E. erythropappus and 15 other species; 10 families were represented by one species and

three species had just one individual. The main families sampled were Myrtaceae,

Melastomataceae and Asteraceae. Families with larger numbers of individuals sampled were

Asteraceae, Melastomataceae, Myrtaceae, and Primulaceae, representing 91% of all

individuals. The five most abundant species, which accounted for 73% of the sampled

individuals, were E. erythropappus (469), Trembleya parviflora (143), Myrsine coriacea (28),

Myrcia venulosa (25) and Myrcia rufipes (21).

Among the 39 identified species, 51% were classified as pioneers, comprising all of

the 5 most abundant species (Table 1). The light-demanding climax (CL) were represented by

36% and the shade-tolerant (CS) climax by 13% of the total amount of species in the E.

erythropappus dominance area.

At the disturbed forest 830 individuals were sampled, belonging to 24 families, 36

genera and 52 species; 30 of the 62 dead individuals identified were E. erythropappus. In 17

families there were only one species, and 7 species presented only one individual. The most

sampled families were Myrtaceae, Melastomataceae and Asteraceae. Melastomataceae,

Myrtaceae, Asteraceae, Primulaceae and Rubiaceae were the families with most individuals

(83% of the total amount). The five most abundant species were Trembleya parviflora (63),

Myrsine umbellata (62), Psychotria vellosiana (37), Vernonanthura discolor (37) and

Baccharis intermixta (34).

40

32% of the species were considered pioneers, comprising three of the most abundant

species (T. parviflora, V. discolor and B. intermixta). (Table 1). The light-demanding climax

species were represented by 45% and the shade-tolerant climax by 23%.

Table 1: Floristic list of tree species identified at the monodominance, the disturbed forest and

the native forest, arranged alphabetically by botanical families and their ecological groups

(EG) (P: pioneer; CL: light-demanding climax e CS: shade-tolerant climax), in Itacolomi

State Park.

Family Species EG M DF NF

Anacardiaceae Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi P X

Tapirira guianensis Aubl. P X X X

Annonaceae Annona emarginata (Schltdl.) H.Ranier P X

Guatteria australis A.St.-Hil. CL X

Guatteria sellowiana Schltdl. CL X X

Aquifoliaceae Ilex theezans Mart. ex Reissek CL X X X

Araliaceae Schefflera calva (Cham.) Frodin & Fiaschi CS X

Araucariaceae Araucaria angustifolia (Bertol.) Kuntze CL X X

Arecaceae Geonoma schottiana Mart. CS X

Asteraceae Baccharis intermixta Gardner P X X X

Baccharis oblongifolia (Ruiz & Pav.) Pers. P X X X

Eremanthus erythropappus (DC.) MacLeish P X X

Piptocarpha macropoda (DC.) Baker P X X

Vernonanthura discolor(Spreng.) H. Rob. P X X X

Celastraceae Maytenus robusta Reissek CS X

Clethraceae Clethra scabra Pers. CL X X X

Cunoniaceae Lamanonia ternata Vell. P X

Cyatheaceae Cyathea corcovadensis (Raddi) Domin CS X

Cyathea delgadii Sternb. CL X X

41

Cyathea phalerata Mart. CL X

Dicksoniaceae Dicksonia sellowiana Hook. CS X X

Euphorbiaceae Alchornea triplinervia (Spreng.) Müll. Arg. P X X X

Croton urucurana Baill. P X

Sapium glandulosum (L.) Morong P X X X

Tetrorchidium parvulum Müll. Arg. CL X

Hypericaceae Vismia brasiliensis Choisy* P X

Vismia guianensis (Aubl.) Pers. P X X

Lamiaceae Aegiphila integrifólia (Jacq.) B.D.Jacks. P X X

Aegiphila sellowiana Cham. P X

Lauraceae Nectandra nitidula Nees CL X

Nectandra oppositifolia Nees P X X

Ocotea diospyrifolia (Meisn.) Mez CL X

Ocotea lancifolia (Schott) Mez CL X

Ocotea sp. - X

Ocotea spixiana (Nees) Mez CL X X

Leguminosae Dalbergia frutescens (Vell.) Britton CL X X X

Inga sessilis (Vell.) Mart. CL X

Machaerium nyctitans (Vell.) Benth. CL X X X

Machaerium villosum Vogel P X

Senna macranthera (Collad.) H.S. Irwin & Barneby P X X

Malpighiaceae Byrsonima coccolobifolia Kunth CL X X

Melastomataceae Miconia chartacea Triana CL X X X

Miconia corallina Spring CS X X

Miconia discolor DC. CS X X X

Miconia sellowiana Naudin CL X

Miconia theaezans (Bonpl.) Cogn. P X X X

Miconia valtheri Naudin P X X

Tibouchina candolleana (Mart. ex DC.) Cogn. P X X X

Tibouchina granulosa (Desr.) Cogn. P X X

42

Trembleya parviflora (D.Don) Cogn. P X X X

Meliaceae Cabralea canjerana (Vell.) Mart. CL X

Cedrela fissilis Vell. * CL X

Monimiaceae Mollinedia sp. - X

Moraceae Sorocea bonplandii (Baill.) W.C.Burger et al. CS X

Myrtaceae Marlierea cf. excoriata Mart. CS X

Marlierea obscura O. Berg CS X X X

Myrceugenia cf. alpigena (DC.) Landrum CL X

Myrceugenia miersiana (Gardner) D. Legrand & Kausel CL X

Myrceugenia sp. - X

Myrcia amazonica DC. CS X X X

Myrcia cf. crocea (Vell.) Kiaersk. CL X

Myrcia eriocalyx DC. CL X X

Myrcia laruotteana Cambess. P X

Myrcia obovata (O. Berg) Nied. CL X X X

Myrcia rufipes DC. CS X X

Myrcia splendens (Sw.) DC. CL X X X

Myrcia subverticularis (O. Berg) Kiaersk.* CL X

Myrcia vauthieriana O. Berg CL X

Myrcia venulosa DC. P X X X

Myrciaria floribunda (H. West ex Willd.) O. Berg. CS X X

Siphoneugena densiflora O. Berg CL X X

Siphoneugena crassifolia (DC.) Proença & Sobral

CL X X

Siphoneugena kiaerskoviana (Burret) Kausel CL X

Siphoneugena sp. - X

Nyctaginaceae Guapira hirsuta (Choisy) Lundell. CL X

Onagraceae Ludwigia anastomosans (DC.) H. Hara P X

Primulaceae Myrsine coriacea (Sw.) Roem. & Schult. P X X X

Myrsine gardneriana A. DC. CL X X X

Myrsine sp. - X

43

Myrsine umbellata Mart. CL X X X

Proteaceae Roupala Montana Aubl. CS X

Rosaceae Prunus myrtifolia (L.) Urb. P X

Rubiaceae Amaioua guianensis Aubl. CS X X

Bathysa australis (A.St.-Hil.) Benth. & Hook.f. CL X X

Cordiera elliptica (K. Schum.) Kuntze CL X X X

Guettarda sp. - X

Psychotria vellosiana Benth. CL X X X

Salicaceae Casearia sylvestris Sw.* CL X X

Sapindaceae Cupania vernalis Cambess. P X

Matayba marginata Radlk. CS X X

Matayba sp. - X

Solanaceae Solanum cladotrichum Vand. CL X X

Solanum swartzianum Roem. & Schult. P X

Symplocaceae Symplocos celastrinea Mart. ex Miq. CL X

Symplocos falcata Brand CL X

Vochysiaceae Vochysia tucanorum Mart. CL X X

Vochysia sp. - X

Winteraceae Drimys brasiliensis Miers CS X

* Species occurred in adjacent areas to the studied fragments and computed only for general characterization.

Phytosociological parameters and community structure

The total density in the monodominance was 2353 ind ha-1

, and total basal area was

12.7 m3 ha

-1. Shannon-Wiener Diversity Index (H') was 2.35 and Pielou`s Equitability Index

(J‟) was 0.63.

Eremanthus erythropappus was the most representative species in the

phytosociological parameters (FR: 6.29%; DoR: 43.65%; DR: 44.10%; IVI: 94%) (Table 2).

It was followed by Trembleya parviflora (34%), dead E. erythropappus (22%), Myrcia

44

eriocalyx (8%) and Myrcia venulosa (8%). The coverage value index followed the IVI just

until M. eriocalyx (4,08%), which makes Asteraceae (E. erythropappus) the cover dominant

at the family level.

According to the parameters used to estimate dominance in relation with the

community, with a 43.6% DoR, a 94% IVI and a 87.7% CVI E. erythropappus was

considered dominant in the study site. The higher frequency and density of pioneer species

give this group more importance (IVI: 199% P, 59% CL and 41% CS) (Table 3). CS had 40

individuals and were in third place with the lowest values for all parameters (FrR: 32,1%;

DeR: 4,6% and DoR: 4,5%).

Table 2: Phytosociological parameters in the monodominance area

Species

Density Frequency Dominance

IVI CVI Abs Rel Abs Rel Abs Rel

Eremanthus erythropappus 1037,5 44,10 100,00 6,29 3,04 43,65 94,05 87,76

Trembleya parviflora 357,5 15,20 90,00 5,66 0,89 12,84 33,70 28,04

Eremanthus erythropappus morta 135,0 5,74 90,00 5,66 0,75 10,82 22,22 16,56

Myrcia eriocalyx 45,0 1,91 70,00 4,40 0,15 2,16 8,48 4,08

Myrcia venulosa 62,5 2,66 50,00 3,14 0,16 2,32 8,13 4,98

Myrcia rufipes 52,5 2,23 60,00 3,77 0,14 2,02 8,03 4,25

Myrsine coriacea 70,0 2,98 10,00 0,63 0,23 3,35 6,95 6,33

Myrcia splendens 37,5 1,59 60,00 3,77 0,09 1,35 6,72 2,95

Clethra scabra 35,0 1,49 60,00 3,77 0,09 1,30 6,56 2,78

Ilex theezans 30,0 1,28 60,00 3,77 0,10 1,38 6,43 2,66

Miconia chartacea 25,0 1,06 60,00 3,77 0,07 1,04 5,88 2,11

Myrciaria floribunda 30,0 1,28 50,00 3,14 0,09 1,25 5,67 2,53

Baccharis oblongifolia 27,5 1,17 50,00 3,14 0,09 1,30 5,62 2,47

Amaioua guianensis 22,5 0,96 50,00 3,14 0,06 0,89 4,99 1,85

Tibouchina candolleana 22,5 0,96 50,00 3,14 0,06 0,88 4,98 1,83

Miconia discolor 22,5 0,96 50,00 3,14 0,05 0,77 4,87 1,72

Myrcine umbellata 25,0 1,06 40,00 2,52 0,07 1,06 4,64 2,12

Myrcia obovata 27,5 1,17 30,00 1,89 0,10 1,50 4,55 2,67

Myrsine gardneriana 20,0 0,85 50,00 3,14 0,04 0,56 4,55 1,41

Baccharis cf. intermixta 25,0 1,06 40,00 2,52 0,05 0,79 4,36 1,85

Piptocarpa macropoda 22,5 0,96 30,00 1,89 0,08 1,22 4,06 2,17

Miconia valtheri 20,0 0,85 40,00 2,52 0,04 0,58 3,94 1,43

Morta 37,5 1,59 30,00 1,89 0 0 3,48 1,59

45

Tibouchina granulosa 20,0 0,85 30,00 1,89 0,05 0,72 3,45 1,57

Miconia theaezans 20,0 0,85 30,00 1,89 0,05 0,71 3,45 1,56

Marlierea obscura 15,0 0,64 30,00 1,89 0,05 0,79 3,31 1,43

Machaerium nyctitans 10,0 0,43 20,00 1,26 0,09 1,23 2,91 1,66

Alchornea triplinervia 10,0 0,43 30,00 1,89 0,03 0,46 2,77 0,89

Myrcia amazonica 10,0 0,43 30,00 1,89 0,02 0,34 2,65 0,76

Dalbergia frutescens 7,5 0,32 30,00 1,89 0,01 0,18 2,39 0,50

Vernonanthura discolor 15,0 0,64 20,00 1,26 0,03 0,43 2,33 1,07

Cordiera elliptica 10,0 0,43 20,00 1,26 0,02 0,35 2,03 0,77

Psychotria vellosiana 7,5 0,32 20,00 1,26 0,02 0,31 1,89 0,63

Vismia guianensis 7,5 0,32 20,00 1,26 0,02 0,23 1,81 0,55

Byrsonima coccolobifolia 5,0 0,21 20,00 1,26 0,01 0,19 1,66 0,40

Senna macranthera 5,0 0,21 20,00 1,26 0,01 0,17 1,64 0,38

Sapium glandulosum 7,5 0,32 10,00 0,63 0,03 0,43 1,37 0,75

Aegiphila integripholia 5,0 0,21 10,00 0,63 0,01 0,16 1,00 0,37

Nectandra oppositifolia 2,5 0,11 10,00 0,63 0,01 0,15 0,89 0,26

Casearia sylvestris 2,5 0,11 10,00 0,63 0,00 0,07 0,81 0,18

Tapirira guianensis 2,5 0,11 10,00 0,63 0,00 0,05 0,78 0,15

Table 3: Phytosociological parameters of ecological groups in the monodominance area

EG

Density Frequency Dominance

IVI CVI Abs Rel Abs Rel Abs Rel

Pioneer 1792,5 82,22 100,00 35,71 5,04 81,25 199,19 163,48

Light-demanding climax 287,5 13,19 90,00 32,14 0,88 14,22 59,55 27,41

Shade-tolerant climax 100,0 4,59 90,00 32,14 0,28 4,53 41,26 9,12

12% of the individuals had a PBH between 10 and 15cm, where 43.7% were alive E.

erythropappus, and 56.3% were other species. That means a proportion of one small

individual to every eight large-sized individuals.

The overall diameter average was 5.9cm, and most individuals were in 3-5cm and 5-

7cm diameter classes. The species distribution was irregular in the first couple of classes,

since there was a difference between the second and the first class. All species presented a

negative exponential pattern from the second class (Figure 1). The diameter distribution was

different between dead E. erythropappus and the other groups (F2;925= 39.84; p< 0,05).

As for the ecological groups, pioneers presented a negative exponential pattern, with

most individuals in the first and second diameter classes. Light-demanding climax and shade-

46

tolerant climax were irregular in the first couple of classes, and then kept a negative

exponential pattern (Figure 2). Variance analysis didn‟t showed difference between the

ecological groups (F2;869 =0.59; p>0.05)

The overall average for the height was 3.8cm. The distribution of individuals in height

showed discontinuation on all groups, mostly in major and minor classes of height (Figure 3).

Most individuals were in the 4.0 to 4.5m class, very close to the overall average. Variance

analysis showed no difference between the categories height (F2;798 =2.85; p>0.05).

Pioneers and CS also presented discontinuation in major and minor classes of height.

On the other way, CL showed a normal pattern of distribution (Figure 4). The species

distribution of ecological groups in height classes were not different between each other

(F2;869 = 0.62; p> 0.05).

In the disturbed forest area, total density was 2075 individuals ha-1

, total basal area

was 13.1m² per hectare. Shannon-Wiener Diversity Index (H') was 3.62 and Pielou`s

Equitability Index (J‟) was 0.90.

Trembleya parviflora was the most representative species in the phytosociological

parameters (FR: 3.86%; DoR: 8.80%; DR: 7.58%; IVI: 20%) (Table 4). It was followed by

Myrsina umbellata (17%), Psychotria vellosiana (16%), dead E. erythropappus (13%), and

Myrsine coriacea (11%). The coverage value index followed the IVI just until M. coriacea

(7.40%), which makes Primulaceae (M. umbellata and M. coriacea) the cover dominant at the

family level.

According to the parameters used to estimate dominance in relation with the

community, with a 8.8% DoR, a 20% IVI and a 16% CVI T. parviflora was considered

dominant in the study site. The higher frequency and density of CL species give this group

more importance (120%, 166% P and 62% CS) (Table 5). CS had 121 individuals and was

47

also in third place with the lowest values for all parameters (FrR: 33,3%; DeR: 15,2% e DoR:

14,0%).

Table 4: Phytosociological parameters at the disturbed forest area

Species

Density Frequency Dominance

IVI CVI Abs Rel Abs Rel Abs Rel

Trembleya parviflora 157,5 7,59 100,00 3,88 0,69 8,80 20,27 16,40

Myrcine umbellata 155,0 7,47 100,00 3,88 0,50 6,41 17,76 13,88

Psychotria vellosiana 92,5 4,46 90,00 3,49 0,64 8,24 16,19 12,70

Eremanthus erythropappus morta 75,0 3,61 90,00 3,49 0,48 6,08 13,18 9,69

Myrsine coriacea 80,0 3,86 100,00 3,88 0,28 3,55 11,29 7,41

Baccharis cf. intermixta 85,0 4,10 90,00 3,49 0,28 3,62 11,21 7,72

Vernonanthura discolor 92,5 4,46 70,00 2,71 0,27 3,51 10,68 7,97

Cordiera elliptica 72,5 3,49 80,00 3,10 0,26 3,34 9,93 6,83

Miconia sellowiana 57,5 2,77 80,00 3,10 0,29 3,69 9,56 6,46

Myrcia amazonica 57,5 2,77 70,00 2,71 0,22 2,81 8,29 5,58

Marlierea obscura 67,5 3,25 60,00 2,33 0,20 2,56 8,14 5,81

Myrciaria floribunda 62,5 3,01 70,00 2,71 0,15 1,87 7,60 4,88

Amaioua guianensis 57,5 2,77 80,00 3,10 0,13 1,65 7,52 4,42

Miconia valtheri 57,5 2,77 60,00 2,33 0,18 2,36 7,46 5,13

Miconia discolor 47,5 2,29 60,00 2,33 0,20 2,61 7,23 4,90

Eremanthus erythropappus 72,5 3,49 40,00 1,55 0,16 2,00 7,05 5,50

Miconia theaezans 37,5 1,81 60,00 2,33 0,21 2,66 6,79 4,47

Miconia chartacea 50,0 2,41 50,00 1,94 0,17 2,23 6,57 4,64

Morta 80,0 3,86 70,00 2,71 0 0 6,57 3,86

Clethra scabra 47,5 2,29 70,00 2,71 0,12 1,56 6,57 3,85

Ilex theezans 35,0 1,69 70,00 2,71 0,12 1,48 5,88 3,16

Siphoneugena widgreniana 42,5 2,05 60,00 2,33 0,12 1,50 5,87 3,55

Myrcia obovata 37,5 1,81 60,00 2,33 0,13 1,65 5,78 3,46

Myrcia splendens 47,5 2,29 50,00 1,94 0,12 1,54 5,77 3,83

Tibouchina candolleana 27,5 1,33 60,00 2,33 0,10 1,29 4,94 2,61

Myrcia eriocalyx 27,5 1,33 50,00 1,94 0,13 1,63 4,90 2,96

Tibouchina granulosa 32,5 1,57 50,00 1,94 0,10 1,26 4,77 2,83

Vochysia tucanorum 15,0 0,72 50,00 1,94 0,12 1,50 4,16 2,22

Sapium glandulosum 10,0 0,48 20,00 0,78 0,21 2,71 3,97 3,19

Miconia corallina 27,5 1,33 40,00 1,55 0,08 0,96 3,84 2,29

Dalbergia frutescens 22,5 1,08 40,00 1,55 0,09 1,12 3,75 2,20

Baccharis oblongifolia 22,5 1,08 40,00 1,55 0,06 0,81 3,44 1,89